Featured Articles

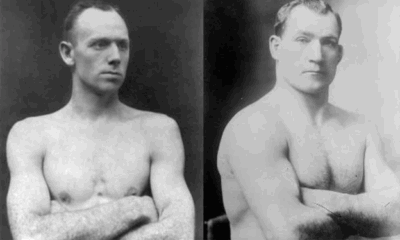

Jack Dempsey’s First Title Defense was a Labor Day Rumpus

Jack Dempsey’s First Title Defense was a Labor Day Rumpus

Throughout history – although not so much anymore – boxing promoters have been keen to hitch their promotions to other allurements. The practice dates to the bare-knuckle era in England where some of the biggest fights were piggy-backed to country fairs, important dates on the horseracing calendar, and other come-ons certain to attract a large crowd. It’s the flip side, one might say, of “build it and they will come.”

In the United States, prior to World War II, there was a lot of activity on the Fourth of July. Some of the most memorable fights in boxing history were staged on that date. Labor Day, a federal holiday since 1894, always held on the first Monday of September, wasn’t as busy but didn’t lag far behind.

Jack Dempsey made the first defense of his heavyweight title on Labor Day weekend in 1920, opposing Billy Miske. The match was staged in Benton Harbor, Michigan, and therein lies a tale that is sterling Americana.

Benton Harbor

Benton Harbor sits in the southwest tip of Michigan on the shores of the big lake. In 1920, Benton Harbor was home to about 12,000 people, roughly the same number that reside there today although the demographics have changed. Nowadays, the population is 85 percent African-American.

Across the St. Joseph River lay Benton Harbor’s sister city St. Joseph. The communities were connected by a trolley line.

Both towns had amusement parks. The one in Benton Harbor was owned by the House of David, a religious sect nationally known for its barnstorming baseball team. St. Joseph was about the same size as Benton Harbor but attracted many more tourists in the summertime because it had the best beach in the county.

One could access Benton Harbor by car, train, or boat. The journey by train from Chicago was roughly three-and-a-half hours. (Amtrak currently runs a non-stop train between Chicago and St. Joseph; the trip takes about two hours.) But despite easy access, Benton Harbor was still a peculiar place to hold a big prizefight. The nearest major city was South Bend, Indiana, 45 miles away.

Floyd Fitzsimmons

Whenever an important prizefight pops up in an unusual place, there’s a man with great vision (or foolhardiness) making it happen. In Benton Harbor, that man was Floyd Fitzsimmons.

Fitzsimmons first love was baseball. Before he promoted his first fight, he was the owner, manager, and occasional right fielder of Benton Harbor’s semi-pro baseball team, the Speed Boys. On the side he managed a few boxers, joining the scrum to find a Great White Hope to unseat Jack Johnson.

On the Fourth of July in 1912, he promoted a card at the House of David baseball park featuring the well-known Wisconsin middleweight Eddie McGoorty in a 10-round contest. The fight was stopped by the police seconds before the final bell and Fitzsimmons, who refereed the match, and the two combatants were taken into custody for violating Michigan’s boxing law which allowed only “exhibitions.”

They would be acquitted and, over the next few years, Fitzsimmons promoted only sporadically, zig-zagging according to whether or not the law was vigorously enforced, which varied depending on which governor was in the statehouse.

On July 4, 1920, he brought the first world title fight to Benton Harbor. Benny Leonard defended his world lightweight title with a ninth-round stoppage of Charley White. To hold it, Fitzsimmons built a 12,000-seat stadium, a saucer-shaped arena surrounded by a barbed wire fence. It would be enlarged to accommodate Dempsey vs. Miske.

Dempsey.

Although his fame increased exponentially, Jack Dempsey didn’t become an overnight sensation on July 4, 1919, when he demolished Jess Willard to win the world heavyweight title. In his14 fights preceding his match with the “Pottawatomie Giant”, Dempsey scored 12 knockouts, eight in the opening round including a 23-second KO of Fred Fulton, a man who outweighed him by 20 pounds.

After crumpling Fulton, Dempsey was firmly on the radar screen of even the most casual of fans. The Manassa Mauler was Mike Tyson before Mike Tyson.

After brutalizing Willard, Dempsey was inactive for 14 months. During this period, he spent most of his time in Hollywood where he starred in “Daredevil Jack,” a 15-episode silent movie melodrama. Concurrently, “The Life and Adventures of Jack Dempsey,” written by Eye Witness (purportedly Damon Runyon) was serialized in American newspapers.

Miske

Minnesota’s Billy Miske was well-acquainted with Dempsey. They had fought twice before, a 10-rounder in St. Paul and a 6-rounder in Philadelphia, bouts spaced six-months apart in 1918. Dempsey won both fights in the eyes of ringside reporters. In the second meeting, Miske did a lot of clinching after Dempsey gained the upper hand.

It spoke well of Miske, a solid pro with some nice wins to his credit, that Dempsey could not stop him. In fact, the “St. Paul Thunderbolt”, an eight-year pro, had never failed to go the distance. But few gave him a chance of defeating Dempsey.

A writer for a local paper provided a checklist for bettors. He gave Miske the edge in ring generalship, rating Dempsey superior in punching, speed, temperament, physique, and condition, the latter of which took on an added dimension after reports circulated that Miske had recently had his tonsils removed. (He was suffering from Bright’s Disease, an insidious malady that would take his life within four years. Billy Miske passed away on Jan. 1, 1924, at age 29.)

Benton Harbor on the day of the Big Fight

Sept. 6, 1920, Labor Day, would be described as the most festive day in the history of Berrien County. In the morning of the big fight, over 400 members of the American Federation of Labor, grouped according to their specialty (plumbers, carpenters, etc.), paraded from Benton Harbor to St. Joseph preceded by marching bands from neighboring towns. At night, an illuminated airplane bearing two stunt pilots circled about the entwined cities shooting fireworks “recklessly about the heavens.”

The number of visitors overwhelmed the accommodations. “A large number of unfortunates could not get sleeping quarters, and put in the nights in automobiles and wherever else covering could be had” said a story in the St. Joseph paper. An enterprising resident secured a large number of Army cots and pup tents that he rented “at exorbitant cost” for use in public parks. Price-gouging was rampant. The going rate for a night in a bed in a private home, breakfast excluded, was $8 ($127 adjusted for inflation).

Prelims

Dempsey vs Miske were preceded by two 6-rounders. Both went the distance.

Big Bill Tate, who stood six-foot-six, defeated Sam Langford in a drab fight in which very few punches were thrown. It was their sixth meeting in what would eventually be a 9-fight series. Langford, the fabled Boston Tar Baby, was then well past his prime.

In the second prelim, the semi-wind-up, Harry Greb was a clear-cut winner over Chuck Wiggins, the “Indiana Playboy.” Otto Floto, the dean of American boxing writers, described the entertaining match as “six slashing rounds which chased thrills across the spinal column.” (Floto’s round-by-round report was telegraphed to his paper, the Kansas City Post, and then megaphoned from the Post’s second-story office to the crowd gathered in the street below.)

It was Greb’s fourth win over Wiggins in as many tries. They had fought 17 days earlier in Kalamazoo and twice the previous year in bouts spaced three days apart in Toledo and Detroit. (Note: Of the six boxers that appeared on this card, four – Dempsey, Greb, Langford, and Miske – would be enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame.)

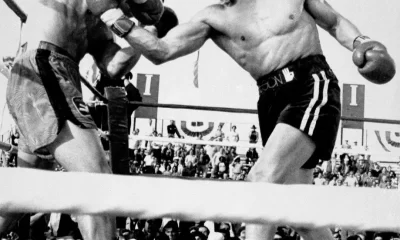

Dempsey vs. Miske: The Fight

The law in Michigan restricted fights to 10 rounds and stipulated that no decision could be rendered. Hence, the only way that Dempsey could lose his title is if he were knocked out or disqualified.

That wasn’t going to happen.

Dempsey knocked Miske down in round two with a punch that landed just under Miske’s heart, landing with such effect that a large red blotch immediately appeared in the affected area. In the following round, he decked him again, this time with a short right hand to the jaw. Miske bravely drew himself upright, rising at the count of “9,” only to be greeted by the same punch in the same spot, knocking him unconscious.

Big Bill Tate and Harry Greb had served as sparring partners for the champion so it was a clean sweep for Team Dempsey.

The official time of the stoppage was 1:13 of round three. Despite his deteriorating health, Billy Miske soldiered on, having 23 more fights, winning 21. In a career consisting of 105 battles, only Jack Dempsey was able to knock him out.

The aftermath

A post-fight story in the Benton Harbor paper left the impression that the visitors were well-behaved, but there were more than a few bad eggs among the attendees. Later that month, at a convention in St. Joseph, Berrien County Democrats passed a resolution urging the governor to tighten the screws because the big fight “brought pickpockets and burglars and bootleggers and other questionable characters into Berrien County in heretofore unheard of numbers.”

The governor was receptive, more so upon learning that the state boxing commission, whose members were appointed by his predecessor, had spent more than two thousand dollars on tickets to the Dempsey-Miske fight, meant to be given away as gifts, and so Fitzsimmons, under duress, moved his tack 45 miles south across the state line to Michigan City, Indiana, another lakefront community where the Chamber of Commerce welcomed him with open arms.

Floyd Fitzsimmons

Michigan City was roughly twice as large as Benton Harbor and had better accommodations for tourists. What it lacked was a suitable arena for a big fight, so Fitzsimmons went and built one, a larger arena than the one he had left behind in Benton Harbor.

Fitzsimmons first Michigan City promotion arrived on July 4, 2022. Lightweight champion Benny Leonard knocked out Rocky Kansas in the eighth round. Fitzsimmons then signed up Jack Dempsey for his Labor Day event – it was to be a rematch with Bill Brennan – but that fight was axed by the authorities. Indiana’s boxing law was similar to that of Michigan and there was no way that one could get away with packaging a match for Jack Dempsey, a murderous puncher by nature, as nothing more than an exhibition. (Fitzsimmons salvaged the date by arranging a bout between bantamweights Joe Lynch and Memphis Pal Moore, both future Hall of Famers. Lynch won a 12-round newspaper decision.)

Fitzsimmons most extravagant promotion in Michigan City pit Georges Carpentier, the French Orchid Man, against St. Paul’s Tommy Gibbons who had stayed the limit with Dempsey in Shelby, Montana. The May 31, 1924 promotion, which filled the arena to capacity, attracted a colorful crowd. “Smartly gowned women, business men and bankers rubbed shoulders with the riff-raff of Chicago,” wrote the correspondent for the Indianapolis Star. Among the notables in attendance was New York’s charismatic mayor Jimmy Walker who seldom missed a big fight.

It mattered greatly that Indiana’s anti-prizefighting governor had resigned the previous month, yielding his post to the lieutenant governor who had a more charitable view of the fight game. Tommy Gibbons won the 10-round contest wire-to-wire, leaving Carpentier a sorry sight.

—

When Floyd Fitzsimmons left the field of sports promotion, he became a lobbyist for parimutuel horse and dog racing. In 1948 he went to prison for bribing a Michigan state legislator to vote favorably on a horse racing bill. Sentenced to 3-4 years, he spent his entire stay in the prison hospital with a heart condition and was paroled within a matter of months. He passed away in Benton Harbor on June 21, 1949 at age 65.

A lifelong baseball fan, Fitzsimmons died while listening to a radio broadcast of a game between the Chicago Cubs and Boston Braves. At his Requiem High Mass, the centerpiece was a huge floral arrangement from his great friend Jack Dempsey.

Happy Labor Day

—

A recognized authority on the history of prizefighting and the history of American sports gambling, TSS editor-in-chief Arne K. Lang is the author of five books including “Prizefighting: An American History,” released by McFarland in 2008 and re-released in a paperback edition in 2020.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThis Day in Boxing History: Surprise, Legacy, and Transition

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThis Day in Boxing History: Fights that Made November 10th Unforgettable

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThis Day in Boxing History: From St. Louis to Buenos Aires

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoResults and Recaps from Texas where Vergil Ortiz Demolished Erickson Lubin

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThis Day in Boxing History: A Date for Heavyweights, Shockwaves and Momentum

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: The Swedish Alliance and More Fight News

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThis Day in Boxing History: Monzón’s Rise and Leonard’s Redemption

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThis Day in Boxing History: Legacy, Redemption and Reinvention