Book Review

Literary Notes from Thomas Hauser

Literary Notes from Thomas Hauser

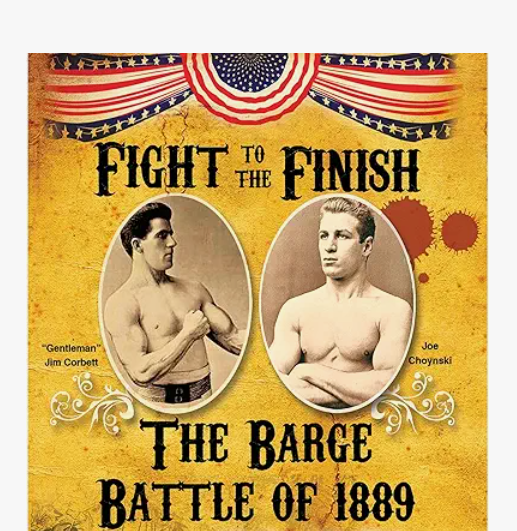

Fight to the Finish by Ron J. Jackson Jr (Eakin Press) is an interesting read. The book is devoted to the bitter rivalry between James J. Corbett and Joe Choynski, described by Jackson as “two young men locked in an intense struggle to emerge from San Francisco’s hard streets with their own version of the American Dream.”

“Corbett and Choynski were destined to fight,” Jackson writes. “They were on the same path at the same moment in time. They lived only a mile apart but ran in separate circles. They even brawled once on the streets and quickly developed a blood feud.”

Choynski came from a well-educated Jewish family but was thought of as a street fighter. Corbett was the son of poor Irish immigrants but had worked as a bank teller and was affiliated with San Francisco’s prestigious Olympic Club. An Irishman vs. a Jew. One street gang versus another. Choynski could fight. Corbett could box. Each man knew how to counter the skills of the other. For some, a Corbett-Choynski battle was a matter of ethnic pride. For the fighters, it was a question of who was the best fighter in San Francisco.

On May 30, 1889, Corbett and Choynski met for their long-awaited confrontation in a barn near San Anselmo in Marin County. But the bout was stopped by the police short of a definitive resolution. Six days later, they fought again; this time on a barge anchored off Dillon’s Point near Fairfax, California. Three hundred spectators watched the carnage unfold. The fighters were so bloodied that, as the savagery wore on, buckets of water were thrown on them to wash off the blood. Corbett won by knockout in the twenty-seventh round.

Jackson spent four years researching Fight to the Finish and drew upon every primary source that he could find. He calls his work an effort to “preserve this epic battle and all of its social and cultural ramifications in 1889 San Francisco for future generations.” To a degree, he has accomplished that end. The Corbett-Choynski fights and the circumstances leading up to them are dramatically reconstructed and engagingly told.

But there’s a problem. It’s hard to know how reliable the telling is.

Jackson recreates long-ago conversations based on multiple sources, some of which are of questionable veracity. When he relies on Corbett’s own memoir (The Roar of the Crowd), it requires the caveat that “many of the details are factually inaccurate” and “Corbett likely embellished his stories to put a finer polish on his image and legacy.” Indeed, at one point, Jackson acknowledges, “Sometimes Corbett’s tales grew like Jack’s beanstalk.”

For example, Jackson recreates a scene (taken from Corbett’s autobiography) where a bully named Fatty Carney picks a fight with Corbett after school: “Corbett found himself instinctively bobbing his head, sidestepping the much huskier Carney, and flicking jabs.”

No! Schoolyard fights don’t work that way. And boxing certainly doesn’t. One doesn’t instinctively bob and weave successfully and throw jabs without training.

Many of Jackson’s other sources (including Nat Fleischer) told similarly allegorical tales. And there are places where Jackson simply gets his facts wrong. At one point, he writes that John L. Sullivan preferred bare-knuckle fights to fighting with gloves. But the polar opposite was true. Sullivan preferred to fight with gloves and wore them in all but three of his recorded bouts.

Similarly, Jackson quotes a longtime Choynski friend as saying, “Choynski was the first Jewish boxer to make a stir in fistiana.”

What about Daniel Mendoza (known as “Mendoza the Jew”), the famed prizefighter and boxing instructor who revolutionized boxing in Regency England?

Factual errors like these make it hard to fully trust the rest of Jackson’s narrative. So where does that leave us?

Corbett’s place in ring history has been long assured as a consequence of his 1892 victory over John L. Sullivan. Meanwhile, Choynski has receded into the fog of time. Thar’s a shame.

Choynski had a notable ring career that lasted from 1888 through 1904. His credits included a third-round knockout of a young Jack Johnson and draws against Bob Fitzsimmons, James J. Jeffries, and Marvin Hart – all in non-title bouts. Sadly, Corbett refused to give him a rematch regardless of how large a financial incentive was offered. And Choynski never had the opportunity to fight for the heavyweight championship.

Fight to the Finish paints a vivid portrait of Corbett and Choynski and gives both men their due.

*****

Mike Silver is a knowledgeable boxing historian with passion for the sport. So, when he writes a book, it deserves reading. But unlike Silver’s previous efforts, When in Doubt, Stop the Bout (Hamilcar Publications) is short on history. Instead, it criticizes the usual targets (corrupt sanctioning bodies, politicized state athletic commissions, greedy promoters and managers, inept trainers, incompetent and/or biased referees and judges) and offers a series of reforms that Silver says would make boxing safer.

“Is enough being done to make professional boxing less dangerous?” he asks rhetorically before answering, “If I thought the answer to that question was ‘yes,’ this book wouldn’t be necessary.”

There are two components to When in Doubt, Stop the Bout. The first is what has been a common theme in Silver’s writing – trashing contemporary boxers and the contemporary boxing scene. The second consists of his safety recommendations. Let’s start with the first of these themes.

As I’ve written in the past, there are two components to writing history: (1) get the facts right, and (2) interpreting the facts.

Silver is a reliable reporter of fact. But there are times when I take issue with his interpretation.

For example, when I read The Arc of Boxing (Silver’s first book about the sweet science) seventeen years ago, I felt that he had gone overboard in glamorizing the past and denigrating contemporary fighters. I simply don’t agree that Tami Mauriello at 190 pounds would have knocked out Lennox Lewis or that Tommy Loughran at 185 pounds would have outpointed Mike Tyson. Nor did I think that Bernard Hopkins in the 1950s would have been nothing more than a “good journeyman” or a “main event fighter in the small clubs.”

Silver is entitled to his opinion, and I’m entitled to mine. I think his thoughts as referenced above are unfounded. When in Doubt, Stop the Bout continues in that vein.

“Boxing,” Silver writes, “used to be called the art of self-defense. But it has become, instead, a sport of artless offense, especially since the 1990s.” He then cites a lack of quality trainers capable of teaching their charges proper defensive skills and points a finger at managers who put their fighters in overmatched situations and state athletic commissions that allow obvious mismatches to take place. Next, he turns to improperly-prepared referees, ring doctors, and cornermen.

There’s validity to some of these criticisms. But as before, there are times when Silver’s glorification of the past goes beyond reason. For example, he writes, “Every top contender of the 1920s to the 1950s would have been a dominant world champion today.”

That’s nonsense. I have some old issues of The Ring, so I looked at the top-ten rankings for the period ending November 15, 1950. Does Silver seriously claim that Clarence Henry or Omelio Agramonte would be a dominant heavyweight champion today? Or that Arthur King, Mario Trigo, and Art Aragon (all ranked in the top-ten at 135 pounds) would rule the lightweight division?

Similarly, Silver proclaims, “If we could time-travel Golovkin, Lomachenko, and Crawford back several generations, they would be considered promising prospects but wouldn’t yet be ready to challenge for a world title.”

I think that assessment is completely off the mark.

And returning to the issue of mismatches . . . Henry Armstrong (one of the greatest fighters ever) fought twenty-seven fights in 1937 and won all of them, twenty-six by knockout. But some of Armstrong’s opponents that year were Varias Milling (52 wins in 113 fights), Pete DeGrasse (75 wins in 150 fights), Mark Diaz (22 wins in 64 fights), Eddie Brink (37 wins in 77 fights), Orville Drouillard (44 wins in 88 fights), Johnny DeFoe (23 wins in 49 fights), Joe Marciente (53 wins in 135 fights), and Joey Brown (19 wins in 53 fights). These men were cannon fodder by the time Armstrong fought them. And the same could be said about many of the fighters that Sugar Ray Robinson and Archie Moore knocked out, not to mention Joe Louis’s “Bum of the Month” club.

That brings us to Silver’s recommendations as to how to make boxing safer. I agree with some of his suggestions and disagree with others.

The proposal at the heart of Silver’s reforms is to limit fights to five three-minute rounds with fights of up to ten rounds allowed “in limited circumstances.” Reducing the number of scheduled rounds in fights, he says, is necessary to “make up for the inexperience and poor defensive skills shown by most contemporary boxers.” He then adds “With boxer’s defensive skills at an all-time low and hundreds of inexperienced boxers subjecting their brains to unnecessary trauma, limiting the number of rounds is a not only justifiable but essential. Shortening fights would limit exposure to head trauma while not wholly eliminating boxing’s excitement and brutality.”

Would reducing the number of rounds in fights reduce brain damage? Sure. And making football games shorter would reduce brain damage too. In each instance, there would be fewer blows to the head. But in making his suggestion, Silver is ignoring the fact that CTE and other forms of brain damage are caused by blows to the head suffered in the gym, not just in fights. In fact, blows suffered in the gym may well be more responsible for CTE in fighters that blows sustained during fights.

Next, Silver writes that better training for trainers would lead to boxers being more skilled defensively and getting hit in the head less often. That’s a nice thought. But better training for trainers would also lead to fighters delivering punches more effectively. And more to the point, Angelo Dundee (one of boxing’s best trainers) trained Muhammad Ali. George Benton and Lou Duva (two of the best) trained Meldrick Taylor. Yet both Ali and Taylor were horribly scarred by boxing.

Silver calls for referees and ring physicians to be more vigilant in stopping fights. I agree with that. He advocates for use of a standing eight-count when a fighter is hurt but still on his feet – a tool I support as a means of evaluating whether a fighter is fit to continue. He also says that a fighter’s corner should be allowed to stop a fight by throwing in the towel at any time. I wholeheartedly agree with that.

However, I disagree with the notion that head guards should be mandatory for fighters. Head guards might decrease the number of cuts that a fighter suffers. But they increase the punching area and would lead to more blows landing on a fighter’s head.

Also, there’s virtually no mention in Silver’s analysis of the use of illegal performance enhancing drugs. PEDs in boxing aren’t a matter of running faster or hitting a baseball further. They lead to fighters being hit in the head harder.

When in Doubt, Stop the Fight contains some interesting nuggets from a historical perspective. Silver notes that, in the first hundred years after the Marquis of Queensberry Rules (requiring padded leather gloves, three-minute rounds, and a one-minute rest period between rounds) took hold, approximately 1,700 professional and amateur boxers died from injuries suffered in fights. Between 1980 and 2023, 170 professional fighters were killed.

He also notes that, in the eighty-eight years between 1882 and 1980, four fighters won titles in three weight divisions – Bob Fitzsimmons, Tony Canzoneri, Barney Ross, and Henry Armstrong. Over the next forty-one years (1981 to 2022), forty-eight fighters achieved that feat and twenty of them won titles in four or more weight classes. That speaks to the devaluing of the term “champion” in boxing today. But in the end, I finished reading When in Doubt, Stop the Fight with the feeling that Silver’s bias against contemporary boxing clouds his work.

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – The Most Honest Sport: Two More Years Inside Boxing – is available at

In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAgit Kabayel Rallies to Stop Damian Knyba, Claims Interim WBC Heavyweight Title

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoEarly 2026: Boxing Results and Emerging Storylines

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCelebrating Mike Ayala on his Birthday

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective Chap 359 Heavyweights, Super Lights and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArtur Beterbiev: Power, Persistence, and the Pursuit of Boxing Immortality

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThis Week’s Birthdays in Boxing: Three Heavyweights, Three Paths

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCelebrating Roy Jones Jr. and Matt Godfrey on Their Birthday

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoJoe Frazier: The Relentless Heart of a Heavyweight Legend