Book Review

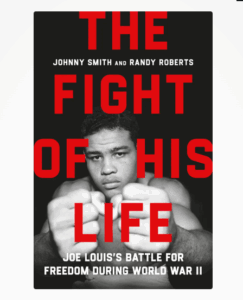

The Fight of His Life: Joe Louis’s Battle for Freedom During World War II

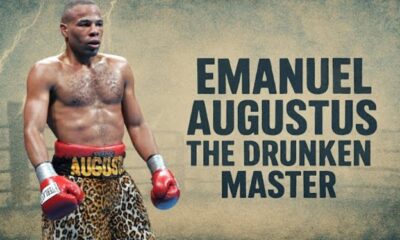

Book Review by Thomas Hauser — In his formative years as a writer, Randy Roberts wrote excellent biographies of Jack Dempsey and Jack Johnson. More recently, he has co-authored several books with Johnny Smith; most notably, Blood Brothers: The Fatal Friendship Between Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X. Now Roberts and Smith have joined forces to write The Fight of His Life: Joe Louis’s Battle for Freedom During World War II (published by Basic Books).

“I would call the book revisionist,” Roberts says, “Certainly, it constitutes a revision of attitudes toward Joe Louis. People don’t think of him as being an activist. Was he Muhammad Ali? No. But during World War II, Louis was an activist behind the scenes in ways that very few people understand.”

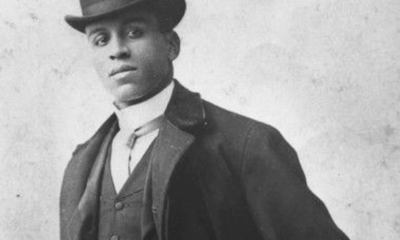

“If chroniclers favor rags-to-riches stories,” Roberts and Smith write, “Louis’s rags phase was as bad as they come. Virtually uneducated, burdened by a speech impediment, he faced daunting odds which did not improve much when his father was committed to the Searcy Hospital for the Colored Criminally Insane in [Alabama] when Joe was about two years old. His life took a slight turn upward when his mother and her second husband moved the family to Detroit, joining the Great Migration of Southern Black people to the urban Midwest and Northeast.”

Then Louis found boxing. At the peak of his career, the authors state, he was a revolutionary force and the most famous athlete in the world. No one else was remotely close. Every time Louis knocked out a white man, he struck a blow against the theory of white supremacy. His 1938 annihilation of Max Schmeling was a metaphor for the battle to come between democracy and Nazi Germany and the first time that many people heard a Black man referred to simply as “the American.”

“[But] except when Louis was especially comfortable with people around him,” Roberts and Smith write, “he wore a mask that was, depending on the observer, blank and devoid of emotions. That expression was one that many Black men – especially those born in the South – learned to wear during their youth. Its dominant feature was a nonthreatening indifference.

Life magazine (then the most popular magazine in the United States) ran a seven-page spread on Louis that called him “the most famous and successful Negro on earth.” But even as Life praised Louis for his boxing conquests, it demeaned him. Earl Brown (a Black man who wrote the profile) portrayed Louis as an ignorant man, interested primarily in eating, sleeping, and watching movies.

“Serious thoughts about his position in the world do not bother the champion,” Brown wrote. “Instead, he spends his days chomping on apples, downing ice cream by the quart, and lounging on a sofa. He snores like a Mack truck when asleep and wallows like a walrus when washing.”

Brown also reported that Louis enjoyed walking barefoot indoors and out and added, “One of his small luxuries is having his corns trimmed by his wife, Marva, with whom his relations are otherwise not altogether flawless.”

Meanwhile, despite strong isolationist sentiment in parts of America, Franklin Roosevelt was working to channel economic aid to England and preparing the United States for war. In September 1940, at his urging, Congress passed the Selective Service Act.

“The law,” Roberts and Smith write, “allowed the War Department to maintain its long-standing policy of segregating military personnel based on race. Furthermore, Roosevelt approved a War Department statement that maintained the US military would ‘not intermingle colored and white enlisted personnel’ in the same regiments because segregation had been ‘proven satisfactory over a long period of years.’ Desegregating the US military, the War Department claimed, would prove ‘destructive to morale and detrimental to the preparations for national defense.’ As for the chances of change, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox assured a gathering of civil rights leaders that he would resign before the sun rose on that day. ‘You see,’ [Knox] said, ‘men live in such intimacy aboard ship that we simply can’t enlist Negros above the rank of messmen.’ Even on the athletic fields, the navy discouraged any mixing of the races. In the spring of 1941, Harvard’s lacrosse coach withheld his one Black player in deference to the Naval Academy’s informal ban on interracial competitions. Football teams playing against Annapolis did the same.”

Then, on December 7, 1941, Japanese forces attacked the United States naval base in Pearl Harbor bringing America into the war.

“On December 8,” Roberts and Smith write, “the same day President Roosevelt asked a joint session of Congress for a declaration of war against Japan, US Army spokesmen assured white Americans that Jim Crow would remain in uniform. Although Army Chief of Staff George Marshall told a group of Black newsmen that he was ‘not personally satisfied’ with the progress against discrimination in the service, the official army position did not reflect Marshall’s view. Only hours after Marshall raised the reporters’ hopes, Colonel Eugene R. Householder, the general’s adviser on race matters, made the army’s position painfully clear. Any attempt by the army to solve racial problems ‘would result in ultimate defeat.’ Echoing [Secretary of War] Henry Stimson, Householder said, ‘the Army is not a sociological laboratory.’”

Roberts and Smith continue the saga:

* “Eruptions of tempers – fueled by an unpopular draft, a segregated army, the discomforts of life in the camps, and the summer heat – threatened the fragile social balance on [military] posts. A jostling on a bus, an angry racial slur, a punch thrown in response – the line between manageable animosity and full-scale rioting was as thin as a razor’s edge.”

* “Stories published in the Black press demonstrated the hypocrisy of America’s professed war aim of fighting for democracy while Black soldiers were treated like convict labor. Screaming headlines in Black America’s newspapers captured the relentless assaults on Black soldiers encamped in Southern outposts. Black soldiers under attack could not fight back without the threat of an armed white mob descending upon them.”

* “Convinced that the Black press was disseminating propaganda that could be used by the Axis Powers, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover coordinated a censorship campaign where his agents interrogated and intimidated Black editors whom he suspected of violating the Espionage Act, a draconian law from the First World War that criminalized free speech. At one point, the Justice Department threatened to shut down Black publications if they didn’t soften their coverage of the military.

Enter Joe Louis.

Roberts and Smith tell the story better than I can. So I’ll let their words tell it.

“In the cramped offices of the War Department, the question was not how to integrate the armed forces or how to improve the conditions for Black soldiers, but how to manage ‘the Negro problem.’ After conducting extensive research and holding endless debates, the War Department maintained its separate but equal policy of ‘segregation without discrimination’ as a necessity for avoiding a race war inside America’s military camps, most of them located in the South. [But] the Roosevelt administration needed a silent symbol, someone who inspired hope among millions of Black Americans without agitating for civil rights or racial equality. For that mission, Uncle Sam called on Joe Louis.

“For the War Department, Louis seemed an ideal figure for dealing with the army’s ‘Negro problem.’ Milton Starr [a wealthy white businessman who owned a chain of forty-nine ‘Negro theaters’ in the South] recommended that the Office of War Information build a propaganda campaign around ‘prominent Negro names’ and faces. Before the Second World War, the US government had never celebrated Black soldiers as war heroes. But there had never been a universally beloved Black hero like Louis, let alone one who served in the military. ‘The Army and the government have a tremendous propaganda asset in Joe Louis,’ Starr wrote. ‘To a great majority of the Negroes, he appears almost as a god. The possibilities for using him are almost unlimited.’”

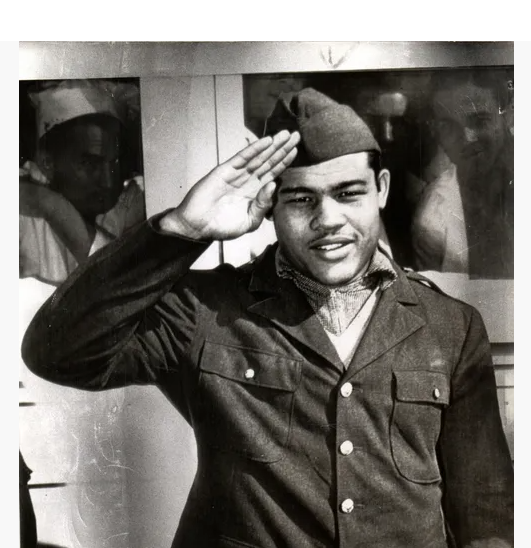

Knowing that he would be drafted, Louis enlisted in the Army and was assigned to its Morale Branch as a goodwill ambassador. “For the first time in history,” Roberts and Smith recount, “the US government built a propaganda campaign around the heroism of a Black soldier, featuring Louis in newspapers, magazines, movies, newsreels, posters, and pamphlets.” His mission was to promote patriotism and unity across American military bases.

Then Mary McLeod Bethune (founder of the National Council of Negro Women) proposed that Louis and other Black boxers tour American military camps in the United States and overseas.

“This unit,” Bethune wrote, “could go to every place in the world, no matter what the dangers may be, and put on a show for our fighting men. Can you picture the reaction a soldier would have to see Joe Louis and other great fighters fly across thousands of miles of enemy-infested lands and waters, just to put on a show for them?”

Thereafter, Roberts and Smith report, “Performing boxing exhibitions and delivering short speeches, [Louis] entertained soldiers and urged them to fight for democracy. In his public appearances, he reassured the government – and white America – that Black folks would fight for the United States and remain completely committed to the mission. In private conversations, he reminded Black servicemen that despite the segregated conditions in the armed forces, they too had a stake in the war.”

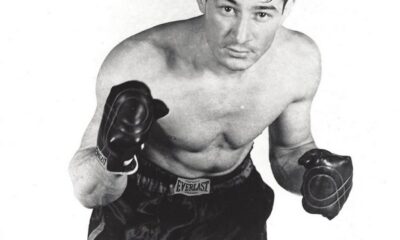

Accompanied by Sugar Ray Robinson (not yet a champion but already a star), Louis visited more than one hundred military sites in the United States, performing for more than six hundred thousand soldiers. Then Louis went overseas and participated in seventy-five more exhibitions in England, Italy, and North Africa.

He also fought Buddy Baer at Madison Square Garden and donated his entire purse to the Navy Relief Fund.

Roberts and Smith scoured old State Department and Department of War records. These documents allowed them to create new scholarship and uncover how much more there was to Louis than the stoic mask he wore in the ring.

“There’s a myth,” they write, “that Louis never spoke out against racism and that he did not think it was appropriate for him to be anything more than a boxer. However, his experience in a segregated army sparked his political awakening.”

“You have to remember,” Roberts told this writer, “Louis was brought up in poverty in the deep south at a time when speaking out could mean prison or even death. On top of that, he had a stuttering problem. So even after the family moves to Detroit, he’s not very verbal. Then he’s groomed as a professional fighter by managers who want him to be the anti-Jack Johnson, so he’s instructed to not talk much. And he’s fighting in a world with largely white sportswriters who, when he does talk, often quote him in demeaning dialect. Now, all of a sudden, he’s thrown into World War II in a segregated army. His managers are gone. He’s forced to grow up.”

“Before the Second World War,” Roberts and Smith continue, “Louis rarely uttered a word, at least not publicly, about the American [Racial] Dilemma. The War Department chose Louis as a symbol because military officials did not expect that he would question the hypocrisy of America battling totalitarianism with a Jim Crow Army.”

However, as a harbinger of things to come, Louis had made speeches in a dozen cities on behalf of Wendell Wilkie (the Republican nominee) during the 1940 presidential campaign because Wilkie had endorsed passage of a federal anti-lynching law while Roosevelt (in deference to southern Democrats) hadn’t.

“The government,” Roberts and Smith write, “misjudged his plasticity. When he was inducted into the US Army, officers handed Louis a uniform, separated him from white soldiers, and directed him to the ‘colored’ quarters. Swallowed by a small crowd of admiring draftees, Louis got routed across the avenue to a company of white recruits. At that moment, a uniformed man yelled to Joe that he didn’t belong in the queue with white soldiers. Louis didn’t say a word. He simply ambled over to the segregated line of young Black men attached to L Company of the Second Battalion. He sat down for lunch with his fellow soldiers in L Company at the ‘Negro’ mess hall and ate his first army lunch: pork chops and bean soup.”

Later, the authors continue, “Louis realized that his popularity as a famous athlete had done little to expand democracy. Being the heavyweight champion didn’t insulate him from racism either. As Louis became more aware of the cruel realities of a segregated army, he began to bristle about his assignment as a goodwill ambassador. The Second World War transformed Louis into the first prominent Black athlete turned activist.”

Roberts and Smith recount several instances in which Louis advocated for Black soldiers facing discrimination in the Army; his friendship with and intervention on behalf of Jackie Robinson during Robinson’s time in the military; and Louis’s refusal on at least one occasion to enter the ring for an exhibition until black soldiers were admitted to a “whites only” venue:

Thirty minutes passed and Joe still had not entered the ring. The white servicemen sitting inside the stadium were growing impatient, clapping and shouting, “We want Louis! We want Louis!” Searching for the champ, a special service officer found him sitting in the dressing room still wearing his army uniform.

“Come on, Joe,” he urged. “Get dressed. It’s time for you to go on.”

Joe told him that he would not enter the ring until the Black soldiers outside the arena were admitted. Fearing an explosive situation, the officer left and returned with the commanding officer, a general, who ordered Joe to put on his boxing trunks and get in the ring.

Sergeant Louis refused.

The general could see that Joe was adamant about his position. The champ wasn’t going to smile and shuffle for a bunch of white soldiers while his Black brethren were denigrated and denied admission. Anxious to avoid an ugly confrontation, the general gave another order: “Admit the Negro soldiers.”

World War II ended in 1945. The Allied forced were victorious. Democracy had prevailed. “Like many Black politicians, activists, soldiers, and civilians,” Roberts and Smith write, “Louis thought that service in the military would earn them the respect of white Americans and ultimately advance their cause for full citizenship.”

They were wrong.

“In the summer of 1946,” Roberts and Smith recount, “White lynch mobs attacked and sometimes killed Black veterans. It was the worst summer of racial violence since 1919 when race riots erupted in more than twenty cities and white vigilantes murdered dozens of Black Americans, many of them veterans. After the Second World War, Black men dressed in military uniforms were again seen as a threat to the racial caste system. Proud patriotic Black GIs returned home victorious, determined to claim their rights as full American citizens. Yet armed white posses unleashed a campaign of terrorism. The lynchings across the South inspired Black veterans to stand up and speak out against injustice and mob violence. Increasingly, they joined the NAACP and other civil rights groups, organizing protests against segregation and lynching. The uprising of 1946 spurred the beginning of the modern civil rights movement.”

Meanwhile, Roberts and Smith continue, “Louis emerged from the war as a voice of an oppressed people. When he returned home from the service, while Black veterans were being attacked by lynch mobs, he spoke out against racial violence and white supremacy. Joining veterans and civil rights activists, he urged Black citizens to fight for voting rights and demand racial equality.”

Finally, in 1948, Harry Truman (who assumed the presidency after Roosevelt’s death in 1945) issued an executive order that declared, “There shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.” Six more years would pass before the United States military fully dissolved all of its segregated units.

Roberts has long been a trustworthy historian. In recent years, Smith has joined him. Their books are always thoroughly researched and transform history into an informative dramatic read.

The Fight of His Life is not a boxing book, although well-crafted portraits of John Roxborough and Julian Black (Louis’s co-managers) and Jack Blackburn (Louis’s trainer) add to its texture and substance. The book also makes the point that, “By the time Louis went in the army, he wasn’t the great Joe Louis as a fighter anymore. He’d fought too often in too short a time – ten times in fifteen months. He was largely used up.”

The only boxing-related point in the book that I’d quibble with is that the authors are kinder than the facts might warrant in recounting the charge that Sugar Ray Robinson went AWOL prior to his scheduled assignment to fight exhibitions in the European theater.

Louis and Robinson, as earlier noted, toured military bases in the United States, engaging in boxing exhibitions for soldiers who were about to be shipped overseas. Then they were sent to Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn preparatory to continuing their tour to boost the morale of American troops abroad. Robinson indicated that he had no interest in leaving the United States. The penalty for desertion was explained to him. At that point, depending on one’s version of events, either Robinson went AWOL or suffered a medical crisis. Either way, on March 29, 1944, he disappeared.

Shortly after midnight on April 1, Robinson was “found” by a stranger on a street in Manhattan. He was taken to a hospital on Staten Island, where he told Army investigators that he had no memory of what had happened during the preceding three days but believed that he had tripped over a duffel bag in the barracks and fallen down a flight of stairs, banging his head and incurring a severe case of amnesia. The examining physicians found no credible evidence of brain trauma. On April 7, Robinson was detained by military police and held for court-martial. Then, for reasons that are unclear, on June 3, 1944 (three days before D-Day), he was discharged from the Army on “medical” grounds. Years later, Robinson asked noted sportswriter W. C. Heinz to ghostwrite his autobiography. Heinz declined because Robinson failed to explain his military history with what the writer thought was sufficient candor. The fact that Robinson never again suffered from “amnesia” and, in 201 professional fights, was never knocked unconscious casts further doubt on his conduct with regard to the Army.

The Fight of His Life also contains very good material on Louis’s relationship with Jackie Robinson. Before they met in the army, Robinson had been a spectacular four-sport athlete at UCLA. He could have played running back in the National Football League but for the NFL’s “whites only” policy.

In March 1942, Robinson was drafted, not by the NFL but by the Army. Roberts and Smith recount, “Robinson reported to Fort Riley with aspirations of becoming an officer. As an intelligent, college-educated soldier, he was certainly qualified for officer candidate school (OCS). When Jack applied, however, he was advised that Negroes were not permitted in OCS at Fort Riley. Listening to him complain about the army’s racist restrictions, Louis shared his outrage. ‘It’s bad enough to have a segregated Army,’ Joe thought. ‘At least some Blacks should be officers over their own people.’”

Later, Roberts and Smith write, “Robinson refused to move to the back of a camp bus at Camp Hood, Texas, when a white driver ordered him to the rear. Two days after his bus protest, on July 8, 1944, the War Department issued a formal directive prohibiting discrimination in military transportation regardless of local civilian custom. The War Department also banned racial discrimination in camp recreational facilities, theaters, and post exchanges, though many officers ignored the order.”

Meanwhile, Robinson’s protest led to his being court-martialed on charges of “insubordination, disturbing the peace, and refusing to obey the lawful orders of a superior officer.” He was found not guilty of the charges.

Louis’s profligate womanizing is honestly told in The Fight of His Life with a particularly interesting recounting of his relationship with singer-actress Lena Horne.

“Like Louis,” the authors write, “Lena Horne carried the hopes and dreams of Black America. She would have to navigate the color line and prove that she was ‘The One,’ the first crossover screen star who could appeal to white audiences without reminding them that she was too Black.”

Roberts and Smith also do a laudable job of debunking many of the myths that surround Louis.

For example, writing about a 1935 meeting at the White House between Louis and Franklin Roosevelt, they state, “The president was impressed with the strapping prizefighter. After asking Louis to flex his bicep so he could feel his muscle, Roosevelt said, ‘Joe, you certainly are a fine-looking young man.’”

“In the coming years,” Roberts and Smith recount, “that story was told and retold until it became a myth that Louis met Roosevelt in the Oval Office on the eve of his rematch against Max Schmeling. According to legend, FDR said in 1938, ‘Joe, we need muscles like yours to beat Germany.’ [But] Roosevelt never uttered that line. [And] he would not have viewed the Nazis as a genuine enemy of the United States [in 1935].”

Many writers (this one included) have repeated that myth as fact. Thank you to Roberts and Smith for the correction.

I always learn something new when I read one of Randy Roberts’ books. That now extends to books written by Roberts and Smith. The Fight of His Life changes a narrative that has been largely accepted for decades. And it’s an important book because it tells hard truths about America’s racial legacy at a time when a concerted effort is being made to deny these truths.

The Fight of His Life is also a reminder of how remarkable Muhammad Ali’s refusal to accept induction into the United States Army during the height of the war in Vietnam was. Ali was criminally indicted for taking that stand. He was stripped of his championship and precluded from fighting for three-and-a-half years when he was at his physical peak.

Why did Ali take that stand?

In 1967, Muhammad answered that question with another question: “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs? If I thought going to war would bring freedom and equality to twenty-two million of my people, they wouldn’t have to draft me. I’d join tomorrow. I have nothing to lose by standing up and following my beliefs. So I’ll go to jail. We’ve been in jail for four hundred years.”

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book– The Most Honest Sport: Two More Years Inside Boxing– is available at https://www.amazon.com/Most-Honest-Sport-Inside-Boxing/dp/1955836329/ref=sr_1_1?

In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoSebastian Fundora: The Towering Inferno’s Ascent in the Sweet Science

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoAnthony Joshua Discharged from Hospital After Fatal Nigeria Car Crash — Latest Updates

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoDecember 26: This Day in Boxing History — Jack Johnson, Muhammad Ali, and Global Heavyweight Legacy

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoDiego Pacheco, Joe Cordina, Tito Mercado, and Skye Nicolson Triumph in Stockton

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoMurat Gassiev KOs Kubrat Pulev in Dubai

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoI’m Betting on Jake Paul … To Live*

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Sweet Science Weekly— December 15, 2025

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoDecember 28: This Day in Boxing History: The Enduring Legacy of George Dixon