Featured Articles

Literary Notes from Thomas Hauser: The Story of Len Johnson and More

Literary Notes from Thomas Hauser: The Story of Len Johnson and More

Len Johnson was born in Manchester in 1902, the first of four children from a mixed-race marriage. His father was black and his mother white. BoxRec.com credits him with compiling a 95-32-7 (36 KOs, 5 KOs by) ring record between 1920 and 1933 but acknowledges that some of his early fights might be unrecorded.

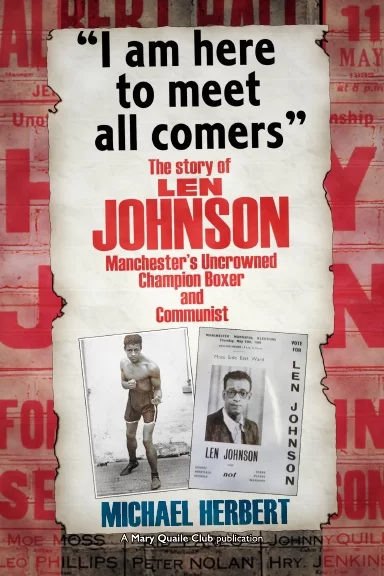

The Story of Len Johnson: Manchester’s Uncrowned Champion Boxer and Communist by Michael Herbert (Mary Quaile Club) explores Johnson’s growing up in Manchester and Leeds; the impact of race and imperialist ideology on British boxing in his time; Johnson’s experience with traveling boxing booths; his professional ring career; and his involvement with the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Johnson fought white opponents throughout his career. But he was precluded from fighting for the British title because of opposition to mixed-race fights at the elite level in England.

The fifth Earl of Lonsdale was a founding member and the first president of the National Sporting Club. In 1909, he gifted the original Lonsdale belts to the club, and they became the club’s official boxing championship trophy. Twenty years later, the British Boxing Board of Control was formed and began the process of consolidating control over the sport. The Board’s regulations stated that contestants for Lonsdale belts were required to be “legally British and born of white parents.”

Speaking of this color barrier, Lord Lonsdale condescendingly noted, “In the case of Len Johnson, we have a very extraordinary position and a very difficult one. Len Johnson was born in England, educated in England and all his associations are English. But he is coloured and, so far as a contest for a Lonsdale Belt is concerned, that rules him out. I am very sorry for his sake because he is a very fine fellow, a really nice man, with a fine personality and a splendid boxer. But there it is.”

The Manchester Evening Chronicler took issue with Lonsdale’s position, editorializing, “Johnson has won his way to the front in the middleweight division and yet is denied the opportunity of competing for the coveted Lonsdale Belt which would set the seal on his fame. Why should a man be debarred from attaining the highest honours at the game merely because he happens to be coloured? Len Johnson is generally regarded as a model of what a boxer should be. Invariably courteous, entirely devoid of any side, he has won through by sheer merit and as such he is surely entitled to be given a chance to reach the topmost pinnacle.”

Johnson seconded that notion, saying, “As a boxer, the greatest ambition of my life is to step into the ring at the National Sporting Club and to prove to the members of that institution which has stood for so much in boxing that I had merited their invitation to box there. I have the national qualifications, and I think I can claim without being regarded as a braggart that my ring history fully qualifies me as being up to the standard required by the controllers of the NSC. And yet I am not allowed to achieve the ambition of my life – to fight in the National Sporting Club of my own country.”

In the end, the forces of repression prevailed, bolstered by views similar to those expressed by Norman Hurst, who wrote in The Sporting Chronicle, “It is not the Len Johnsons, Larry Gainses, George Dixons, Sam Langfords or Al Browns that we have to deal with but the repercussions that are felt all over Africa with its teeming millions of coloured people of quite different mental makeup from any of the above athletes. Urged on by troublemakers, outstanding victories for one of their own colour are usually used as flame to ignite a lot of trouble. This was shown very clearly when Jack Johnson defeated Tommy Burns in Australia.”

In a similar vein, Arthur Conan Doyle (the creator of Sherlock Holmes) supported the ban and declared, “Let black and white keep separate and fight among themselves. Some of the greatest fights in the history of the ring have been between white and coloured men, as when Cribb and Molyneaux met last century. But conditions were not so complex then. The British Empire did not contain so many black people. Nowadays a mixed fight gets beyond sport and enters the region of interracial politics.”

This is the soil in which Johnson’s career was planted. “It was,” Herbert writes, “enough to make him question the values and political structures of British society.”

In 1944, Johnson joined the Communist Party of Great Britain, believing that it was the best vehicle to “lead the fight to mobilize the entire labour movement and fight for the social improvements necessary to help white and coloured people live together in harmony.” Thereafter, Johnson spoke often at Communist Party meetings and was a candidate for local office in six elections, although he received only a small fraction of the vote each time. He remained a member of the party until his death in 1974.

Herbert began researching Johnson’s life in 1982. Ten years later, he self-published a biography of Johnson. New material that became available in recent years led him to update and republish his work.

There are too many fight summaries in Herbert’s narrative – a common failing in fighter biographies. There’s also a lot of political material about the Communist Party in Great Britain that doesn’t relate to Johnson and goes well beyond what’s necessary to place Johnson in the context of his times.

But Johnson’s story is one of those niches in the attic of boxing history that are worth visiting from time to time. The obstacles he faced because of his color are well-told. And Herbert provides a service in recounting the role that boxing booths played in Johnson’s life and the history of British boxing.

The booths, which first appeared in the late-18th century, moved from town to town, charged a fee for admission, and often accommodated several hundred spectators. Men from the crowd were invited to square off against one of the traveling boxers. If a challenger lasted three rounds, he received a cash prize.

Jem Mace is often credited with creating the modern traveling boxing booth. In later years, Jimmy Wilde, Benny Lynch, Tommy Farr, and other British champions got their start there. So did Johnson. Indeed, Herbert recounts that, during one three-day period when the booth he was traveling with was in Nottingham, Johnson boxed 68 fights. And after his formal professional ring career ended, he returned to the booths. At one point, he even owned one.

* * *

Boxing fans have a right to be cynical whenever a promoter, fighter, or anyone else in a position of power says that they’re doing something “for the fans.” Almost always, there’s a bill to be paid and the fans wind up paying it. But last month, as part of building its brand, The Ring did something for the fans. It put the entire 104-year Ring Magazine archive online free of charge.

“It wasn’t easy,” Ring CEO Rick Reeno says. “When we started, there were boxes and boxes of randomly-arranged issues all over the places. And a few hundred issues were missing, especially a lot of the early ones. We bought what we needed to complete the collection, and a company in the UK digitized it all. It wasn’t cheap. And even then, there were problems. From time to time when they were digitizing, they’d call and tell us that a page from one of the magazines was missing.”

Many issues of The Ring from the 1930s through the early-1950s are notable for the full-color paintings that grace their cover. None of the artists will go down in history as being on a par with Rembrandt or Leonardo da Vinci (or even LeRoy Neiman). But their work does catch the eye.

As for the articles, Nat Fleischer (the magazine’s founder, owner, and first editor) was notoriously inaccurate as a historian. But the Ring archive gives readers a window to look through onto a long-ago time. And there are occasional gems from some very good writers.

What are the magazines themselves worth? Craig Hamilton (the foremost boxing memorabilia dealer in the United States) says, “The truth is, once you get past The Twenties and Thirties, there’s not much value to them. Every now and then, a collection comes up. I just bought a full set, bound, from the first issue through 2019 and paid $15,000 for it.”

That leads to an oddity. Some sets were privately bound by collectors with each volume containing one calendar year. But The Ring also sold bound volumes through the 1980s. And at Fleischer’s instruction, each of these bound volumes ran from February through the following January because the magazine’s first issue was dated February 1922. The set that Hamilton bought was an official Ring set supplemented with similarly-delineated, privately-bound later volumes.

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – The Most Honest Sport: Two More Years Inside Boxing – is available at https://www.amazon.com/Most-Honest-Sport-Inside-Boxing/dp/1955836329/ref=sr_1_1?crid=MLXL6UHY8O9E&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.NZgHyDuy4gb1i6YPJ_9vmAMw3oLJh1d9Sxs-G8xJoJY.67ftevZ4BImTjJoSlE9uPWJz-j5i5wJGtSrlNDVZw-g&dib_tag=se&keywords=the+most+honest+sport+hauser&qid=1750773774&sprefix=the+most+honest+sport+hauser%2Caps%2C65&sr=8-1

In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this article in the Fight Forum, please CLICK HERE.