Featured Articles

The Jimmy Clabby Story: The High Times and Horrific Demise of the ‘Indiana Wasp’

Jimmy Clabby was named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame this month and will be formally inducted at the Hall’s annual jamboree in June. Clabby, needless to say, won’t be there. He’s been dead going on 92 years.

Throughout history, many great fighters died under sad circumstances. The case of Jimmy Clabby, the Indiana Wasp, is especially distressing. Clabby was 43 years old when he drew his last breath on a late-January day in a dilapidated shack on the outskirts of a town on the outskirts of Chicago. Starvation, alcoholism, and exposure were listed as contributing factors.

In other words, Jimmy Clabby froze to death.

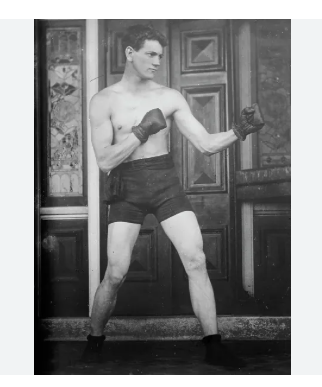

In the ring, Clabby was an anomaly, a defensive wizard, emblematic of his nickname, but with enough offense in his game to be a crowd-pleaser. Outside the ring, with his reddish hair and Irish good looks, he drew admiring glances from women of all ages. No American fighter ever developed a more avid following in Australia.

Born in 1890 in Norwich, Connecticut, Clabby was raised in Hammond, Indiana, the son of a saloonkeeper. A fine baseball player, he found boxing more to his liking and turned pro at age sixteen.

Hammond shares a slice of its border with Chicago. In 1907, when Clabby turned pro, prizefighting in the Windy City was dormant, a residue of the stench from the scandalous 1900 fight between Terry McGovern and Joe Gans. Milwaukee, Wisconsin, two hours away by train, was at the other end of the spectrum. Pro boxing was percolating in Milwaukee with club fights every week, often two on the same night.

Wherever prizefighting sprouts and then flourishes, there’s one wealthy, unswerving sportsman leading the charge. In the Cream City, so named because of the distinctive yellowish bricks that framed many of her buildings, that man was Frank Mulkern, a former newsboy who, like many of the newly rich, built his fortune on the back of automobile makers, introducing metered taxicabs to Milwaukee and surrounding areas.

Mulkern had a great booster and helpmate in Thomas Andrews, the sporting editor of a local newspaper, a man best remembered for producing one of boxing’s first record books. And it mattered a great deal that, in an era when boxing was under siege in many places, Mulkern and Andrews had the support of local politicians. It would be written of Milwaukee Mayor David S. Rose, elected to a fifth term in 1908, that he had a natural antipathy toward moral reform.

In Milwaukee, Jimmy Clabby roomed for a time with future lightweight champion Ad Wolgast whose career was at the same stage of development. On three occasions, they shared the same bill.

Clabby had fought 30 fights in Wisconsin rings, 22 in Milwaukee, when Mulkern took him to New Orleans to meet Jimmy Gardner in November of 1908. Gardner, from Lowell, Massachusetts, was recognized as the world welterweight champion in the state of Louisiana.

After 15 rounds, the referee awarded the match to Gardner but the verdict was unpopular, fomenting a do-over. Clabby and Gardner remained in the city and met again 19 days later. The sequel, a 20-rounder contested on a Thanksgiving afternoon, ended in a stalemate. The aggressor throughout, Clabby had the best of the milling through the first 17 rounds but faded, enabling Gardner to salvage a draw.

Gardner was older and had fought stiffer competition so the close encounters redounded well to Clabby. Moreover, Clabby injured his right shoulder in the rematch and became a better boxer because of it, developing a snappier left hand.

There would be a third meeting, a 10-rounder in Milwaukee, and this bout, like the first two, ended inconclusively. Ringside reporters were evenly divided as to whether Clabby nipped it or if Gardner was entitled to a draw. Clabby’s chief second for this bout was the event’s guest of honor Ad Wolgast, the newly crowned lightweight champion fresh off his epic battle with Battling Nelson. During the evening, both Wolgast and Clabby were presented with large, horseshoe-shaped floral bouquets said to be a gift from Milwaukee’s newsboys.

In the second decade of the twentieth century, in the years preceding America’s entry into World War I, there was a glut of self-proclaimed champions that makes today’s alphabet soup rubble look tidy by comparison. Jimmy Clabby elbowed his way into the ranks of serious welterweight title claimants on May 5, 1910, when he won a 10-round decision over Dixie Kid on a rare visit to New York. “The Wisconsin boy led in every round, dealing out unmerciful punishment,” said the ringside reporter for the New York Globe. (A posthumous inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, Dixie Kid, born Aaron Brown in Fulton, Missouri, was a last-minute replacement for Clabby’s original opponent Mike “Twin” Sullivan.)

Bon Voyage

Jimmy Clabby had five more fights on American soil before beginning the second phase of his career. In the fall of 1910, he sailed off to Australia. With him were three other top-shelf fighters with midwestern roots: Ray Bronson, Billy Papke, and Cyclone Johnny Thompson. The most celebrated of the bunch was Papke, the “Illinois Thunderbolt,” renowned for trading knockouts with Stanley Ketchel in their two vicious middleweight title fights. The voyage took three weeks including a stopover in Suva, Fiji, where the boxers staged an exhibition for the locals.

The junket was a joint venture between Milwaukee boxing interests (Frank Mulkern and Thomas Andrews) and Australia’s premier sports promoter Hugh D. “Huge Deal” McIntosh. Andrews went along as the chaperone, carrying with him several boxes of the “T.S. Andrews’ World’s Sporting Annual Record Book” for sale wherever the boxers appeared.

For his first fight in Australia, Clabby was thrust against New Zealand journeyman Bob Bryant in a bout billed for the world welterweight title. The match was held on Nov. 2, 1910, at Sydney Stadium on Rushcutters Bay where McIntosh had staged the world heavyweight title fight between Jack Johnson and Tommy Burns. Clabby stopped Bryant in seven frames. “His sinister jab punished Bryant with painful regularity,” wrote a ringside reporter who noted that the Indiana lad wouldn’t turn 21 until July of the following year.

In the Land Down Under, Clabby had six fights compressed into 11 weeks. He had so much fun there that he kept coming back. On his last excursion he stayed five years. During this stint, the war was raging in Europe and Jimmy endeared himself to the Aussies by enlisting in the Army where he was deployed as a recruiting specialist. At some of his final fights in Australia, he was introduced to the crowd as Private Jimmy Clabby.

Altogether, Clabby had 44 bouts in the Antipodes, 34 in Australia and 10 in New Zealand. All 34 of his fights in Australia were slated for 20 rounds, and all but 11 went the full distance (a few of these 20-rounders had two-minute rounds). Although he never tipped the scales at more than 162 pounds, at various times he was recognized as the Australian champion in one or more of the four heaviest of the standard eight weight classes.

Clabby met his future wife in New Zealand, a girl said to be “no older than 19.” They married after a whirlwind courtship. Jimmy was previously engaged to the daughter of a man said to be Australia’s wealthiest bookmaker. Lore has it that he stranded her at the altar.

Clabby’s final fight in Australia, on Sept. 10, 1921, was at Sydney Stadium against a modestly skilled middleweight named Frank Burns. Clabby was knocked out for the first time (early in his career he had been stopped a few times on cuts). The end came in round 15 when Burns knocked him out cold with a right to the jaw. Clabby, who looked poorly conditioned, was never in the fight. His old vim and vigor were gone.

He announced his retirement after this fight, which triggered a benefit for him, a custom which dated to the bare-knuckle days in England. At the testimonial dinner, a gala staged at Sydney Stadium, Clabby was presented with a handsome gold watch and a large sum of money.

Jimmy likely needed the dough. From a lifestyle standpoint, Australia was all wrong for him. Betting, particularly on horse races, was ingrained in the sporting life of the country and he was a degenerate gambler. The money he earned in the ring (an estimated $500,000) disappeared as fast as he made it, the erosion accelerating when he acquired a small stable of racehorses as he couldn’t resist plunging on a horse that he owned.

Clabby’s retirement lasted less than a year. He had 10 more fights after returning to America before his career was finally finished. On July 30, 1903, at East Chicago, Indiana, he had what would be his farewell fight. In the opposite corner was Omaha’s rugged but limited Morrie Schlaifer.

It was a predictably sad spectacle. Schlaifer demolished him inside two rounds, knocking him down three times before the match was halted.

There wasn’t much written about Clabby over the next few years other than an occasional note that he had fallen on hard times. In 1932, a dispatch from Milwaukee said he was recuperating in a Milwaukee hospital from a broken leg suffered when he jumped off a freight train. That same year, his New Zealand wife, who bore him three children, sued him for divorce. It was said that she did not know his whereabouts.

The record books say that Jimmy Clabby, the Indiana Wasp, passed away on Jan. 19, 1934, but he may have been dead for several days before his body was found. The New York Times kicked sand on his corpse, metaphorically speaking, writing that Clabby’s final home was a “squalid refuge for tramps [inhabited] by other human derelicts who lived there with him.”

You won’t find Clabby’s name on the list of lineal boxing champions, but he was better than some of the fighters in his era who would be accorded that distinction. He belongs in the International Boxing Hall of Fame and, akin so many boxers who got there ahead of him, his life story reads best as a cautionary tale.

—

TSS editor-in-chief Arne K. Lang, a recognized authority on the history of prizefighting and the history of American sports gambling, is the author of five books including “Prizefighting: An American History,” published by McFarland in 2008 and re-released by McFarland in a paperback edition in 2020.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE