Featured Articles

From Al Jolson to Mark Wahlberg: Hollywood Heavyweights Invade the Boxing Game

On Friday, Nov. 16, on ESPN, Alex Saucedo appears in his first world title fight, taking on WBO 130-pound champion Maurice Hooker. The match between the two unbeatens — Saucedo is 28-0; Hooker 24-0-3 – will play out in Saucedo’s hometown of Oklahoma City.

Hollywood heavyweights Peter Berg and Mark Wahlberg will be rooting hard for Saucedo. They are the cornerstones of Churchill Management, the boutique talent agency that signed up Saucedo and then gathered in 140-pound hotshot Regis Prograis. Berg and his partners also operate the Churchill Boxing Club in sunny Santa Monica, a gym formally called Wild Card West.

Peter Berg has worn many hats: producer, director, screenwriter, actor. He created the TV show “Friday Night Lights” from his film of the same name. Mark Wahlberg needs no introduction. In 2017 he was the world’s highest paid actor. He starred in four of Peter Berg’s movies and played Micky Ward in the award winning film “The Fighter.”

Berg and Wahlberg are merely the latest bigwigs from the world of Hollywood to invest in the future earnings of boxers. In fact, the relationship between boxing and the entertainment industry predates the advent of big Hollywood studios.

During the early years of the twentieth century, there was no bigger star on Broadway than the versatile and astoundingly prolific George M. Cohan. Theatrical producer Sam Harris was the primary backer of two-division world champion Terry McGovern, but Cohan had a piece of Terrible Terry too, as did ring announcer Joe Humphries. In age, Cohan and McGovern were only two years apart. In his free hours, the Yankee Doodle Boy was often seen in McGovern’s company.

Al Jolson made his mark on Broadway before lighting up the big screen in “The Jazz Singer,” Hollywood’s first feature-length talkie. During his heyday, say music historians Bruce Crowther and Mike Pinfold, Jolson “was the most popular all-round entertainer America (and probably the world) has ever known, captivating audiences in the theater and becoming an attraction on records, radio, and in films.”

Jolson was a big boxing fan. One night at LA’s Olympic Auditorium, he became infatuated with Henry Armstrong, a steadily improving fighter who had recently defeated two of Mexico’s best featherweights, Baby Arizmendi and Juan Zurita. Armstrong’s manager, Wirt Ross, was a gambler who periodically had the shorts. Jolson bought the fighter for $10,000. The deal was consummated on Aug. 21, 1936.

What Al Jolson got was a fighter with a 48-10-6 record who was largely unknown outside California. Other than two early fights near Pittsburgh, Armstrong had never fought east of Butte, Montana.

Jolson entrusted Armstrong to Eddie Mead, the manager/trainer of former bantamweight champion Joe Lynch (that’s Mead in the photo, flanked by Jolson and Armstrong) and Al then set about making Hammerin’ Hank a household name. As Armstrong recalled in a 1981 interview with LA Times boxing writer Richard Hoffer, Jolson and Mead hatched the idea of him winning three titles as the only way a black fighter could make headway as a box office attraction with the shadow of Joe Louis looming so large. Armstrong went on to win the featherweight, welterweight, and lightweight titles, in that order, in an 11-month span in New York rings.

In the history of boxing, no one ever “moved” a fighter as adroitly as Al Jolson (Bob Arum would be envious). Of course, it was Henry Armstrong who did the heavy lifting.

It would later come out that Jolson’s friend George Raft, a dancer turned movie actor, routinely cast as a gangster, was a silent partner in Armstrong’s ring affairs. Furthermore, it would be written that Raft was an early investor in the career of future light heavyweight champion Maxie Rosenbloom. In those days, the fight game was thick with underworld characters and Raft, who was pals with racketeer Owney Madden and others of this ilk, fit right in.

In night clubs and concert halls, Al Jolson belted out his songs as he commanded the stage with his effusive body language. Eventually his fame was dwarfed by crooners whose style was more intimate; more laid-back. The giants of the genre were Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra and, like Jolson, they were multi-media stars.

Crosby was a great sportsman. He co-founded the Del Mar thoroughbred track, near San Diego, which opened in 1937, and was the co-owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team from 1946 until his death in 1977. Less well known, he had a piece of middleweight Freddie Steele.

Crosby likely felt an affinity toward Steele because both were products of the Apple State. Steele hailed from Tacoma; Crosby, born in Tacoma, was raised in Spokane. Late in his career, Freddie Steele won the New York State version of the world middleweight title and successfully defended it five times.

In January of 1944, twenty-eight year old Frank Sinatra, flush with money after signing a seven-year extension with the RKO Studio, purchased the contract of beefy Bronx bartender Tami Mauriello. Mauriello, who began his pro career as a welterweight, had twice fought for the NYSAC light heavyweight title, falling short in two tilts with Gus Lesnevich. He would go on to fight Joe Louis before 38,000-plus at Yankee Stadium. The Brown Bomber knocked him out in the opening round.

Francis Albert Sinatra inherited his love of boxing from his father, a Sicilian immigrant who fought professionally under the name Marty O’Brien, compiling a 1-7 record according to research by Thomas Hauser. In 1956, Sinatra hooked up with another fighter, purchasing a 50 percent interest in Robert “Cisco” Andrade, the “Compton Comet.” Andrade went on to compete for the world lightweight title, losing a 15-round decision to title-holder Joe Brown.

In 1974, with his hit TV series “Sanford and Son” going great guns, comedian Redd Foxx launched the pro career of Fred Houpe who had caught his eye while competing in AAU tournaments. A small heavyweight, Houpe, who was given the nickname Young Sanford, was undefeated in 12 fights when he lost a 10-round decision to former amateur rival Duane Bobick. He left the sport two years later, made a brief comeback in the 1990s, and ended his undistinguished career with a record of 14-6. (Houpe may have been the second boxer to break Redd Foxx’s heart. In an interview with an Oakland reporter on the occasion of Houpe’s pro debut, the comedian claimed that as a young man in Chicago he had a piece of china-chinned heavyweight Bob Satterfield.)

As Redd Foxx could testify, were he still alive, sponsoring a young boxer, an aspiring champion, is an expensive proposition that more often than not doesn’t pay off. Forming a syndicate diminishes the risk by spreading out the jeopardy.

Lee Majors, Burt Reynolds, and Motown recording artist Marvin Gaye were part of a syndicate that backed welterweight Andy “The Hawk” Price. The Hawk was good enough to defeat Carlos Palomino and Pipino Cuevas, but no match for Sugar Ray Leonard who knocked him out in the opening round. Ryan O’Neill, Robert Goulet, and Bill Cosby had welterweight Hedgemon Lewis. Trained by the great Eddie Futch, Lewis was 2-3 in bouts billed as world title fights with both wins coming against Billy Backus on Backus’s turf in Syracuse, New York. These syndicates were forerunners of Churchill Management.

Sylvester Stallone did not form a syndicate when he became interested in Lee Canalito. The architect of the “Rocky” franchise wanted Canalito all to himself.

A great defensive lineman in high school (a Parade All-American) and at the University of Houston before his football career was derailed by a chronic knee injury, Canalito made his pro debut at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach with Angelo Dundee in his corner. He had four fights under his belt when Stallone spied him on TV in a preliminary bout on a show that included the Spinks brothers. Stallone was then seeking an unknown actor to play his brother in a movie he had written and would star in, “Paradise Alley,” and when he saw Canalito (here flanked by Stallone and co-star Armand Assante) he found his man. Canalito, who bore some facial resemblance to Stallone, had the look that Sylvester was seeking.

Stallone eventually took over Canalito’s ring affairs. Canalito was 8-0 when Stallone purchased his contract. He installed the boxer in a guest house on the grounds of his spacious Pacific Palisades estate and the two often lifted weights and did roadwork together. The noted photographer Neil Leifer captured the scene in a five-page spread for Life magazine. Stallone’s hoped-for real-life Rocky, nicknamed the Italian Stallion, was a hot commodity before he ever touched gloves with an opponent who had the skill to give him a serious test.

Canalito, who customarily carried 250 pounds on a six-foot-five frame, never fought a top shelf, or even a mid-shelf, opponent. The well-coddled heavyweight was 21-0 with 19 knockouts when he lost interest in boxing and went home to Houston where he currently operates a fitness center, but only five of his victims had winning records when he fought them.

Stallone, far more so than predecessors like Al Jolson, could see that a boxer’s potential earnings weren’t limited to his purses. Churchill Management has taken it a step further. In its prospectus, the company says, “Churchill Management is the first of its kind, a promotional and commercial agency that represents an innovative approach to assist professional boxers with branding, marketing and public relations.” One surmises they will be adding more boxers to their stable in the near future.

Thus far, Alex Saucedo and Regis Prograis have done their part to justify Berg and Wahlberg’s faith in them. Saucedo’s last fight, against Lenny Zappavigna, was a humdinger and Saucedo walked through fire before stopping the Aussie in the seventh frame. The torrid fourth round between Saucedo and Lenny Z was one for the ages.

Who knows if Churchill Management will still exist in a few years? Their clients must keep winning to manifest the company’s vision for them and, to borrow an old Larry Merchant line, boxing is the theater of the unexpected. Regardless, it’s a safe bet that down the road we will see more Hollywood heavyweights dipping their toes into the business side of the boxing game.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

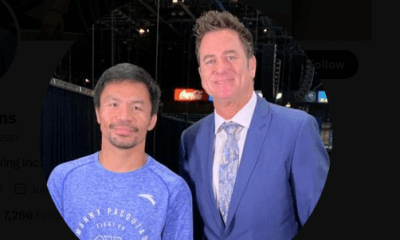

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons