Featured Articles

The Fifty Greatest Light-Heavyweights of All Time Part Five – Nos. 10-1

If I have given the impression that I have been a little disappointed in the depth of talent at light-heavyweight, those thoughts can now be banished. Here is a top ten that very nearly put itself together. Harold Johnson drew the short straw and washed up at #11 but him aside there were really no suitors for the top ten that are not ranked within it. Here be dragons.

So listen.

This, is how I have it:

#10 – MATTHEW SAAD MUHAMMAD (49-16-3)

It is both strange and surprising that Matthew Saad Muhammad, born Matt Franklin, has so few in the way of acolytes in this modern era. Muhammad, sometimes, seems to garner less admiration than that which he deserves, despite the fact that he has all the attributes necessary for a fighter to gather fans in excess of his standing.

He’s unquestionably world-class, and proved it against a huge array of talents and styles; he has one of the most compelling backstories in the entire history of boxing (Google if you aren’t familiar with it); and most importantly of all, he was one of the most exciting fighters of his, or any other era. He was like a huge Arturo Gatti with the crucial difference that he tended to hammer his top-ranked foes rather than be hammered by them.

His apprenticeship ended in March of 1977 with a loss to Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, after which he went on a tear through perhaps the most densely packed light-heavyweight division in history.

Matthew Saad Muhammad was matched tough early, and this, combined with either a learned strength drawn from the adversity he experienced in his tragic childhood or an innate toughness born of genetics, meant Muhammad was ready to engage in and emerge victorious from perhaps the most astonishing shootout ever captured on film. Marvin Johnson, a top fifty light-heavyweight in his own right, dug deep to close the class gap he suffered against Muhammad and turn their astonishing 1977 encounter into the most savage brawl ever seen at the weight. Muhammad triumphed after some of the most terrible exchanges in the history of filmed boxing, in the twelfth, leaving the all-but invincible Johnson staggering around the ring like a zombie. The two split just $5,000.

{youtube}UArIOikqodk{/youtube}

Their rematch early in 1979 was another good fight even if it did not quite reach the heights of their first. Muhammad stopped Johnson in eight to lift a light-heavyweight strap. A strap is all he would ever hold. Muhammad never lifted the lineal title, which lay dormant between the departure of Bob Foster and the arrival of Michael Spinks. But Muhammad was the most significant claimant of this time. In addition to Johnson he defeated the excellent Richie Kates in six and twice dispatched the superb Yaqui Lopez in two great fights in eleven and fourteen rounds. John Conteh managed to make the distance in one contest but was slaughtered in four in the rematch; four, too, was the limit for the fearsome Lottie Mwale. Between his 1977 defeat of Johnson and 1981 when the wars caught up with him and Dwight Muhammad Qawi stopped him in ten, he was almost as splendid a light-heavyweight as can be seen.

Almost.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: John Conteh (#29), Marvin Johnson (#27).

#09 – JIMMY BIVINS (86-25-1)

I’m sorry to play the same old tune but…the heavyweights got him.

In the summer of 1943, weighing 174.75lbs, Bivins was matched over fifteen rounds with the lethal Lloyd Marshall, 164.5lbs, for the duration light-heavyweight title, so named because titlists were able to hold their championship only for the duration of time that the champion – in this case, Gus Lesnevich – was in the armed forces. Marshall, as dangerous a fighter of his poundage as there ever was, and perhaps the best super-middleweight to emerge before that weight division, was coming off twin defeats of Anton Chistoforidis and Ezzard Charles and in the form of his life. Bivins was favoured but much credence was given to the rumours that the two had met in sparring some years earlier, a spar that ended when Bivins had to be rescued from Marshall’s tender attentions. It seemed history would repeat itself, as Marshall came out fast in pocketing the first three rounds, provoking a stern reaction from Bivins who dominated the next three; when Marshall dropped Bivins to take the seventh it seemed another corner had been turned, but Bivins picked himself up, shook himself down and won every remaining round up until the eleventh, which seemed a share. A tired Marshall succumbed to a series of lefts topped off with a vicious right to the cheekbone in the thirteenth.

Then Bivins headed north to the heavyweights, where I rank him at #40. His loss to the history of the light-heayweight division cannot be overstated. Bivins was one of the greatest, and head-to-head one of the most dangerous, light-heavyweights in history.

He was never beaten at the weight. A clutch of heavyweights defeated him while he was weighing in under 175lbs, but that does not concern us here. Anton Christoforidis bested him at middleweight – but in his prime years of 1941, 1942 and 1943, spent almost exclusively at and around the light-heavyweight limit, Bivins ran 14-0 against other light-heavyweights. The level of competition he bested was extraordinary.

In 1941, he defeated, among others, the great Teddy Yarosz, the deadly Curtis Sheppard and Nate Bolden. In 1942 he defeated former middleweight strapholder Billy Soose, reigning light-heavyweight champion Gus Lesnevich (in a non-title fight) and future champion Joey Maxim. In 1943, he dropped the legendary Ezzard Charles seven times on his way to a ten round decision victory; former champion Anton Christoforidis over fifteen rounds; and the deadly Marshall.

For those keeping score, that is a little better than a champion a year, more if you allow middleweight title claims. Bivins was a wrecking machine at 175lbs. He was monstrous.

He did great work at heavyweight too, but that work concentrated at the lighter poundage would have made one of the very greatest 175lb careers.

Of course the #9 slot is nothing to be sniffed at – but one of the many areas where light-heavyweight is marked different from heavyweight is the distinctive differences between the #3 slot and the #9 slot. Probably the former was not out with Jimmy’s grasp. The latter, he very much earned.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Anton Christoforidis (48), Gus Lesnevich (39), Joey Maxim (33), Lloyd Marshall (18), Ezzard Charles, (Top Ten).

#8 BOB FOSTER (56-8-1)

A heavyweight a year beat the tar out of Bob Foster up until his 1965 dull but one-sided loss to Zora Folley. Earlier, thrashings at the hands of Ernie Terrell and Doug Jones convinced him, I think, that light-heavyweight was the division for him. The result was one of the greatest title-runs in light-heavyweight history.

This was despite the fact that champion Jose Torres was less than keen on meeting him in the ring. When middleweight legend Dick Tiger stepped up to light-heavyweight, Foster smelled his chance. Tiger had, as he saw it, been frozen out of the middleweight title picture before moving north and had the will and heart to step in with any man. When Tiger retained in a rematch with Torres and Foster blasted out the superb Eddie Cotton in just two rounds, the fight was imminent.

Foster summarised his stylings beautifully after his destruction of Cotton as “jab, jab, jab, then wham!” This sounds too basic to be true of a legitimate all-time great, but it is the essence of Foster’s strategy. Technically proficient without being a true technician, he was gifted with height and reach but took true advantage of neither, fighting in a strange crouched posture that undervalued his 6’3 frame. The point was, Foster wanted to make his opponents hittable. Whether that was through controlling them with his world-class jab to create openings or through initiating exchanges out of which he always – always – emerged victorious, making punching opportunities was the key to his style. This is because Foster is, perhaps, the hardest p4p puncher in the history of boxing.

That point is arguable, but it is also true that those arguments mean little. The truly great punchers are not survivable. Debating who was the more deadly puncher pound-for-pound between Bob Foster and Sam Langford is a little like arguing about what kind nuclear warhead will leave you more deceased. The handful of punchers that lie at the absolute top of the power tree hit people and those people fall asleep.

Tiger fell asleep when he put the title on the line against Foster. Tiger hadn’t been knocked out in ten years of title fights; Foster knocked him out completely. Unaware that he had visited the canvas Tiger spoke only of darkness and silence. The reign of terror had begun.

Foster’s level of competition is sometimes criticised and in this type of company you can understand why. It is true that his was not an era that provided great opposition, but interestingly there were granite chins in abundance. Chris Finnegan had been stopped before, on cuts – but the devastating one-two Foster laid him low with saw him counted out, lurching in the ropes, his brave attempt at Foster ending in a disaster for his brainstem. Frank DePaula was stopped just twice in his career, but Foster turned the trick in a single round with a crackling right uppercut. No softening his man up; no wearing his man down – when he lands, it’s over. Henry Hank lost thirty-one fights in his career but Foster was the only fighter able to stop him. Mark Tessman was stopped only once by concussion and that concussion was inflicted by Foster’s punches. “Punch resistance” was a meaningless phrase for any light-heavyweight that shared the ring with Foster. The only way to survive was to avoid being hit.

Foster lost to a 180lb Mauro Mina when he was 11-1. No other light-heavyweight defeated him. He was 15-0 in title fights. His reign lasted seven years. While Bivins and Muhammad defeated far and away the better opposition, Foster’s total dominance of the division and my sneaking suspicion that Foster would have poleaxed even those great men, sees him sneak in here ahead of both.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: None

#07 – JOHN HENRY LEWIS (97-10-4)

John Henry Lewis met Maxie Rosenbloom on four separate occasions and the end result was 2-2. But in the two matches that Lewis lost, the men weighed in as heavyweights; Lewis tipped the scale at 182 and 186lbs respectively. When these two elite light-heavies met nearer the light-heavyweight limit, there was only one winner and that was Lewis. What surprises here is that Maxie Rosenbloom was the light-heavyweight champion of the world for these two ten-round non-title meetings, and that John Henry Lewis was a teenager. In fact, he was still at high-school. It didn’t stop him dropping Rosenbloom with a right to the jaw in the first and a left to the kidney in the second in their second meeting in the summer of 1937. Dominating the incumbent champion and then dealing with school the very next day marked Lewis out as something special as he had always been marked out as something special. He first pulled on the gloves as a toddler. He turned professional as a middleweight aged just seventeen. And although he had to wait two years after first defeating Rosenbloom to get his hands on a world champion in a title fight, when he did so he didn’t miss that chance, out-pointing Bob Olin (who had taken the title from Rosenbloom a year earlier) over fifteen in October of 1935. Lewis had already beaten Olin; and Tony Shucco and Young Firpo and Lou Scozza and Rosenbloom. His resume, before he even came to the title, was excellent. Over the coming years he would turn it into something truly extraordinary.

His first defence was staged against #2 contender Jock McAvoy. Lewis, still just twenty-one years old, turned in a performance great maturity and ring-craft, jabbing and counter-punching his way to a decision booed by the crowd for its efficiency rather than any sense that McAvoy had been cheated. Len Harvey, the British and Commonwealth champion was next for a tilt at the title, but before travelling to London to master him, Lewis found the time to dust off Tony Shucco, Al Gainer and former strapholder Bob Godwin, his level of competition remaining outrageously high.

His next defence was a little softer, granting faded ex-champion Bob Olin the rematch he craved and putting him away in eight rounds. “He is the perfect boxer…the best boxer in the world,” Olin later said of his old foe. “He’s fast on his feet with full knowledge of all the scientific departments of the game.” Presumably Emilio Martinez would have agreed with him, succumbing in four rounds, before the perennially ranked Al Gainer pushed him harder over fifteen late in 1938. A late rally protected his title and ensured that he would retire the undefeated light-heavyweight champion of the world. Lewis didn’t just go unbeaten as champion though; he went undefeated at 175lbs. He was never beaten in a match made within 5lbs of the light-heavyweight limit. He was invincible there, dominating a tough era with speedy boxing, a superb left hand and an innate toughness that was only ever beaten from him by heavyweight champion Joe Louis, who stopped him for the first and only time in his career in 1939. Lewis retired shortly thereafter, his eyesight failing him.

One imagines the division let out a collective sigh of relief. Lewis had terrorised it.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Al Gainer (#38), Tiger Jack Fox (#25), Maxie Rosenbloom (#15)

#06 – TOMMY LOUGHRAN (90-25-10; Newspaper Decisions 32-7-3)

A thread has run through this series on the greatest 175lb fighters of all time and that thread is my regular disagreement with history. Whether it’s Sam Langford, the great men of the pre 175lb era generally counted lightheavies by traditionalists or the thorny issues of Billy Conn and Battling Levinsky, I’ve found myself on the rough side of apparent historical truth on numerous occasions. Here, at the sharpest of sharp ends, my trickle of truth finds its way to history’s raging torrent. I add my modest voice to a chorus of more famous names in saying:

Tommy Loughran was one of the greatest pugilists of all time.

Nat Fleischer ranks him at #4, all time, as did legendary boxing man Charley Rose; the IBRO ranks him #6. He appeared at #6, too, on Boxing Scene’s top twenty-five and that is where he is ranked here. This kind of greatness lies on a distant shore and Loughran inarguably belongs there. Simply put, it is impossible to have a list of ten light-heavyweights without placing Loughran somewhere upon it. He was that special, and he proved it.

He proved it first with his record of note standing at just nineteen years old when he was slung in against the immortal Harry Greb. Loughran lost, inevitably, over eight rounds but he won admirers in doing so and impressed with his performance in the opening two rounds and in a sudden desperate rally in the last. He even managed to cut Greb, who spoke in glowing terms of the prospect.

So Loughran matched Gene Tunney.

Again, he did so over eight rounds in a fight generally held to be a draw in 2015. “Not many boxers could outbox Tunney at this stage of his career,” wrote Tunney biographer Jack Cavanaugh. “But Loughran was one of them.”

This statement is far from inarguable but it bears examination. Tunney was one of the very best boxers of his era and is regarded to this day as one of the finest boxers of all time; Loughran, on the other hand, was a teenager. But he was a teenager with perhaps the most cultured, brilliant left hand in history. I’ll say that again: it is possible that the fighter blessed with a better left than Tommy Loughran is yet to be born.

Whatever the details it is a fact that once Loughran made it out of his teens and into his prime, Gene Tunney took nothing more to do with Tommy Loughran. One man who never shirked a challenge, however, was Harry Greb. Loughran fought Greb on a further four occasions, going 1-1-2, defeating him over ten rounds in October of 1923 in a rough contest from which Loughran emerged with the decision via a stern and consistent body-attack.

Most of the other luminaries of the era fell to him too, including Mike McTigue (from whom he took the light-heavyweight title), Jimmy Delaney, Georges Carpantier, Jimmy Slattery, Young Stribling, Leo Lomski, Pete Latzo, Jim Braddock, at which point, as the reader will be unsurprised to hear, the heavyweights got him.

But not before Loughran had staged the fifth of his six victorious world-title fights against Mickey Walker. This was not just a special fight because Walker was so outstanding but also because readily available film survives. Walker, a nightmare for boxers even up at heavyweight, was handled by Loughran. Mickey’s strategy against his timeless jab was to dip and bulldoze but Loughran just tucks his right hand in behind the former middleweight champion’s elbow, adding a superb body attack to his effortless outside game. So successful is this strategy that Loughran begins to feint with the jab to open up the body, and soon Mickey is moving back; Loughran adjusts, re-arranges his jab, throws it, and opens up Mickey’s body again.

Loughran has no qualms about holding Walker while he hits him, he was no saint, but when Walker dips and lifts driving his head into Loughran’s, chin he makes no complaints. He was a shotgun stylist, a renaissance painter who made art with a surgeon’s blade.

Let’s meet the men who keep him from the top five.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Mickey Walker (#36), Jimmy Slattery (#34), Young Stribling (#23), Jimmy Delaney (#14), Harry Greb (Top 10).

#05 – MICHAEL SPINKS (31-1)

As I wrote in Part Four, when contenders passed Dwight Muhammad Qawi they did so on tiptoe, and holding their breath. He was a monster. Two months before Spinks was to take to the ring with this monster, his common-law wife and the mother of his young daughter was killed in a car accident. Just days before the fight he wept openly in front of members of the press – and on the night of the fight?

Nothing.

No glimmer of emotion. Here was a man in absolute control of himself, a professional.

“I live the life of a fighter. I program myself as a fighter.”

Spinks assumed absolute control in the ring, and when his control was challenged he had the tools to equalise the situation with extreme prejudice. Marvin Johnson challenged him, as Marvin Johnson was wont to do, in March of 1981, directly attacking Spinks, and arguably winning all three of the opening rounds in doing so. Spinks backed up, appraised his man, and then delivered an uppercut so brutal that Johnson was unable to continue in its wake. This is the same Marvin Johnson, it should be remembered, that Matthew Saad Muhammad was unable to lay low with three dozen flush power-punches.

So Spinks could be as destructive as he was brilliant, and he was certainly brilliant. When he got to the ring containing Qawi in March of 1983, at stake, the lineal light-heavyweight championship of the world, not only did he show no fear but he showed that brilliance. He dominated Qawi with his jab, and if that brutal sawn-off shotgun of a fighter had his successes against Spinks, there was only one winner. From distance he crackled jabs around Qawi’s head, and when Qawi drew close he found clubbing right hands from an elevated position and a guard-splitting uppercut that snapped the smaller man’s head back repeatedly.

But most of all he controlled Qawi, he forced Qawi to fight his fight, he forced Qawi to jab with him by making himself unavailable for other punches, with cunning, beautifully judged distancing. Malleable in the extreme, his style appeared to be that of a technician, but he had a disjointed approach to building momentum that left rhythm-breakers useless and made learned skills of no practical value to a certain kind of fighter. There are few clues as to what Spinks will throw next.

This occasionally made opponents cautious and led to boring matches where Spinks neglected to take unnecessary chances and his opponents neglect to take any. But he was as capable of the explosive and unexpected as he was of the prosaic.

He staged four defences of the lineal title he finessed and clubbed from Qawi before abandoning it for the heavyweight division, undefeated at 175lbs. There is no company in which Spinks need bow his head – there are other light-heavyweights in his class, but none in excess of it. In some imaginary light-heavyweight maelstrom of greatness, a division made up of the top ten described here, he would excel – if I were betting a single coin on who would emerge as the champion, I might just put it on Spinks.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Dwight Muhammad Qawi (#21), Marvin Johnson (#27), Eddie Mustafa Muhammad (#32).

#04 – GENE TUNNEY (65-1-1; Newspaper Decisions 14-0-3)

I’m not convinced, entirely, that Gene Tunney belongs above the likes of Michael Spinks and Tommy Loughran. What tipped the balance in the end is their respective paper records. Loughran slipped up a few times. Tunney was defeated just once.

And that defeat could hardly be deemed “a slip up.” Tunney lost to Harry Greb, past his absolute prime but still phenomenally dangerous and on the night of the first of five meetings between the two, Greb thrashed Tunney as brutally as he ever thrashed any man; both boxers and the referee finished the contest covered in Tunney’s blood.

The blood was not blue. Tunney’s beginnings were typically working class. But he would raise himself, partly through boxing, all the way to the summit of what passed for American aristocracy, the walking embodiment of the American Dream. Tunney knew that what the US loved most was a winner – this meant that Tunney had to find a way to do the seemingly impossible: he had to find a way to defeat Harry Greb.

He got his first chance to do so nine months later in Madison Square Garden, the site of his ritual slaughter in the first fight, and the officials thought he did enough – Tunney was awarded a split decision victory over fifteen rounds. The result remains one of the most controversial in boxing history. One time trainer of the legendary John Sullivan and the first chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission William Muldoon named the decision “unjustifiable.” Of twenty-three newspapermen polled at ringside, only four found for Tunney; the New York herald went further than many naming the decision “the most outrageous ever awarded in New York.” It is arguable that Tunney did not, then, achieve an unfettered victory in the first rematch, but in the second rematch, their third fight, at the end of 1923, Tunney achieved victory. In September of 1924 the two boxed a draw in their fourth and final fight at the light-heavyweight limit.

Tunney was a Rolls-Royce of a fighter, beautifully balanced with an exquisite left, a digging right (he scored a sizeable number of knockouts with that punch at the weight), he was a solid body-puncher and a world-class counter-puncher. It was a combination that saw him defeat every light-heavyweight he ever met, bar none, Leo Houck, Battling Levinsky, Fay Kesier, Jimmy Delaney and Georges Carpantier among them.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Battling Levinsky (#27), Jimmy Delaney (#14), Harry Greb (Top 10).

#03 – HARRY GREB (107-8-3; Newspaper Decisions 155-9-15)

I suspect that Harry Greb’s high placement above, even, Gene Tunney, may cause some consternation among readers. The internet is awash with accounts of his thousand-glove attack and his supernatural speed, so allow me, instead, to take a purely statistical approach in defence of Greb’s placement.

There are forty-nine other men listed on this top fifty at 175lbs. Greb beat ten of them. In other words, he defeated 20% of the men on this list – nobody, nobody listed above and nobody listed below come anywhere near this statistically. Nor is it the case that Greb cornered past or pre-prime versions of these men. On the contrary, he fought, for the most part, series with each of them over the course of their careers. He gave Jack Dillon two chances at him, beating him firmly the first time and thrashing him the second; Jack Delaney got a second chance but ran 2-0; Tommy Loughran, who shared Greb’s prime, was rewarded with five shots at the great man and for the most part he was beaten firmly. Battling Levinsky received no fewer than six shots at Greb, mostly in no decision contests and in every one of them the newspapermen in attendance favoured the Pittsburgh man. Harry Greb may have been the most dominant fighter in history, and he did a huge swathe of his best work at light-heavyweight.

As for his losses at 175lbs, despite meeting the highest level of competition of any light-heavyweight in history, they were few and far between and often inflicted in what may politely be referred to as “circumstances.” He met the deadly Kid Norfolk on two occasions, getting the best of him first time around only to find himself disqualified in a second contest marred by brutal fouling by both men – eye-witness accounts almost universally decry the disqualifying of Greb but not Norfolk as ridiculous. As we have seen, Gene Tunney holds a legitimate victory over him, winning their December 1923 contest by most sources, but his victory from February of that year is disputed.

Greb twice defeated Tommy Gibbons within the 175lbs limit, but did also drop a decision to him; Loughran managed to win one out of six against “The Pittsburgh Windmill.” He has three legitimate losses at the weight all against all-time greats listed in the top twelve here, men who he also defeated. In total, he holds wins against seven men from the top twenty.

What is disturbing about Greb’s body of work at 175lbs is that even if you removed for some obscure reason his five most significant wins, he would still be bound to the top twenty by his resume, which would very probably remain superior to that of Matthew Saad Muhammad or Roy Jones. Small for a light-heavyweight and famously a fighter of whom no film appears to have survived, his head-to-head ability is inferred by his overwhelmingly positive results against all-time greats, including those of a very modern appearance, like Tommy Loughran and Tommy Gibbons.

Rather than questioning whether or not Greb belongs in the top three, I submit that his absence from the top two is a better cause for curiosity.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Billy Miske (#44), Jimmy Slattery (#34), Battling Levinsky (#27), Kid Norfolk (#20), Jack Dillon (#19), Maxie Rosenbloom (#15), Jimmy Delaney (#14), Tommy Gibbons (#12), Tommy Loughran (Top Ten), Gene Tunney (Top Ten).

#02 – ARCHIE MOORE (185-23-10)

There’s a two-pronged response to the question as to Greb’s placement outside the top two, and the first part of that answer is “Ancient” Archie Moore, the Mongoose. Of course, he wasn’t always ancient but Moore served his lengthy and extreme apprenticeship in the middleweight division before dual losses to the legendary Charley Burley and the mercurial Eddie Booker sent him scampering north to the light-heavyweight division aged twenty-eight. Holman Williams, one of the true monsters of the Murderer’s Row that haunted Moore, elected to follow him and took from him the narrowest of decisions; Moore showed the determination that would carry him to the absolute outer reaches of what is possible for a fighting man in re-matching Williams and becoming only the second man to score a stoppage over one of the best pure-boxers of that or any other era. Moore, as we recognise him today, had arrived.

He became the second man, too, to score a knockout over Jack Chase, another shadowy destroyer from the absurd depths of the middleweight division that now lay below him, defeated Billy Smith, the monster who dispatched Harold Johnson with a single punch – Moore’s own domination of the great Johnson began shortly thereafter. There were disasters, too – the one round knockout loss to Leonard Morrow, although avenged, is hurtful and there were DQ losses that leads one to question what would become one of the great ring temperaments, but it is a fact that Moore had yet to summit at 175lbs. Arguments about whether or not he would actually improve as a fighter are for another day, but what is inarguable fact is that Moore did not come to the light-heavyweight title until late 1952. He was thirty-six years old.

The key, I think, to Moore’s emergence from a pack of fighters to whom he did not prove his inherent superiority (Charley Burley, Holman Williams, Jack Chase, et al) was his ability, perhaps unparalleled, to mount campaigns at heavyweight and light-heavyweight simultaneously. From almost the moment he stepped up to light-heavy he was making matches, too, north of that weight. Moore was using the heavyweights as a tool, I suspect, to enhance his standing as a light-heavyweight, as well as one by which to procure cash.

Whatever the details, his strategy worked and once Moore finally succeeded in getting his opponent into the ring he did not let him off the hook. Maxim fought with astonishing heart, but it is likely that the only round he won was the fourth, awarded to him by the referee after Moore landed a low-blow. That low blow aside, it was a perfect performance and one of the best title-winning efforts on film. Down the years Moore has somehow become perceived by many as a counter-puncher, a fighter who fought in a shell rather like James Toney, waiting for and then pouncing upon chances created by his opponent’s mistakes. Nothing could be further from the truth. Moore was aggressive, marauding but never cavalier. Maxim, easy to hit but hard to hit clean, was just target practice for the Mongoose. He found the gaps that represented half-chances for other fights and made fulsome opportunities of them. His left hook, as short a punch of its kind as can be seen, became a cover for his step in, an industrial elevator of a punch starting at the hip and terminating – well, anywhere, in a singular swift motion. His sneak right which in the first round was a clipping, careful punch, was, by the end of the fight, a steaming dynamo of a punch and one that left the granite-chinned Maxim reeling. Inside, Moore dominated with sniping uppercuts and a savage two-handed body-attack.

By the end, Maxim was desperate. Chewed upon the inside, stiffened by winging punches on the outside, it is great testimony to his heart that he survived the championship rounds. The reign of the greatest ever light-heavyweight champion had begun.

His reign lasted nine years and spanned ten title fights in which Moore went 10-0. These included his astonishing defeat of Yvon Durelle in which he was battered to the canvas three times in the first round and once more in the fifth; of course he survived, of course he stopped Durelle in the eleventh – he had the heart of a lion and the soul of an antique lighthouse. He was in his forty-fourth year. At the time of his final defence against Giulio Rinaldi, he was in his forty-sixth. Moore did not carry out this miracle, like the astonishing Bernard Hopkins, in an era of universal healthcare for fighters who went out twice a year. He did it in an era during which African-American pugilists spent the night before their latest fight in the barn-loft of a local promoter and went out nine times in a year, as Moore did in 1945.

His astounding longevity in tandem with the greatest reign in light-heavyweight history has him near the very pinnacle of this list. All that keeps him from the #1 spot is his very own demon.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Joey Maxim (#33), Lloyd Marshall (#17), Harold Johnson (#11), Jimmy Bivins (Top Ten).

#01 – EZZARD CHARLES (95-25-1)

Moore didn’t like to talk about Ezzard Charles. He loved to talk about Charley Burley. He often expressed his admiration for Rocky Marciano and Eddie Booker and his dislike of Jimmy Bivins. But he did not talk much about Ezzard Charles.

Telling ghost stories is no fun if you live in a haunted house.

The two met first in the spring of 1946 in a fight which was not particularly competitive. Charles was so much better than Moore that referee Ernie Sesto scored the fight ten rounds to zero in Ezzard’s favour; each of the judges found a single round for the Mongoose. It was skill that did it that night and a jab that Moore must have found himself trying to slip in his sleep.

Almost a year to the day after their first meeting they clashed again. Between their first and second meeting they had defeated, between them, Billy Smith, Jack Chase, Jimmy Bivins, Lloyd Marshall and a clutch of other decent fighters. They were untouchable, but to one another. The rematch was closer, so close that Moore could almost touch the win but the result was a majority decision loss, one judge favouring the draw. The deciding factor was likely a single punch, a left hook to the body which dropped Moore in the seventh and caused him to stall thereafter.

Moore was a giant of a fighter but nothing beat larger or stronger within him than his heart. Inevitably he would seek out a third shot at Charles and inevitably Charles would accommodate him. Here was Moore’s moment and he was determined not to let it slip. He began cautiously, boxing defensively, leading at the beginning of the eighth in the main because Charles had two rounds taken from him due to borderline low-blows, but in that fatal three minutes, he opened up in earnest. He jabbed to Ezzard’s mouth and Charles began to bleed. He whipped over that sneaky left hook to Ezzard’s ear and Charles was staggered. That crackling right-hand whipped through and Ezzard was staggered again.

On the cusp of defeat, Charles rescued himself and sealed his greatness forever. Some will even tell you that what followed was nothing less than the springing of a trap that called for him first to be hit and hurt. The two piece that he landed in desperate retort began with a left hook to the temple but the right-hand that followed was described by Pittsburgh journalist Harry Keck as “seeming to travel a complete circle” before it cracked home on Archie’s chin. It was a punch that Moore later claimed he had not seen, and knew nothing of, except darkness.

So there he stands, Ezzard Charles, close to darkness himself, wide-eyed over the quivering form of a detonated nervous system that will in a matter of moments belong again to Archie Moore, unassailable in his greatness. Three times Moore stepped to him and three times Charles defeated him. In the second and third confrontations this difference was arguably a single punch, the fine line between #1 and #2, no more and no less than that.

For despite Moore’s incredible age-defying title reign, he cannot be placed here above Charles. Imagine for a second what it would mean for Joe Louis had he three times defeated Muhammad Ali. There would be no more arguments about which of these two belongs at the top of the heavyweight tree. It is true that Charles did not achieve all that Moore did in the light-heavyweight division. In the aftermath of his knockout of Moore he was labelled a certainty to receive a title shot but Lesnevich, naturally, ducked. In a sense he can hardly be blamed. The single fight film to have emerged of the light-heavyweight Charles is terrifying. Fast, poised, deadly, with a body attack even more savage than Moore he appears unboxable. A fighter as special as Lloyd Marshall seems a boy to a man.

So inevitably, the heavyweights beckoned for the denied light-heavyweight contender and he excelled there too becoming the heavyweight champion of the world, but not before he had defeated, mostly in a dominant fashion, the great names amassed in the greatest light-heavyweight division, including Teddy Yarosz, former middleweight titlist Ken Overlin, light-heavyweight champion Joey Maxim, light-heavyweight champion Anton Christoforidis, the legendary Lloyd Marshall, Jimmy Bivins, Oakland Billy Smith and a swathe of other contenders.

He did not show the spooky longevity of Moore and nor was he permitted to lay a claim to the light-heavyweight title so many great men would throw aloft before and after him, but he did prove beyond all hope of contradiction his inarguable superiority to Archie Moore. This, in tandem with the other fighters he laid low at the weight, is enough to make him the greatest exponent of the fistic art ever to weigh in at 175lbs.

For those of you who have taken the time to read this series of articles from the first word to the last: I thank you.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Anton Christoforidis (#48), Joey Maxin (#33), Llloyd Marshall (#17), Jimmy Bivins (Top Ten), Archie Moore (Top Ten).

Featured Articles

At Long Last: Marvelous Marvin Hagler to Finally Get His Statue in the ‘City of Champions’

At Long Last: Marvelous Marvin Hagler to Finally Get His Statue in the ‘City of Champions’

Not much good news comes out of Brockton, Massachusetts these days but I’ve got some.

Former undisputed middleweight champion Marvelous Marvin Hagler will be posthumously honored in the city he helped keep on the boxing map with a life-sized bronze statue produced by Brodin Studios in Kimball, Minnesota. The statue of Hagler, “in an action stance” will be unveiled on June 13th at a small space near to where the old Petronelli Gym was once located.

According to Hagler’s widow Kay, the space is now called the Marvelous Marvin Hagler Park.

That date, June 13, 2024 will be on the 43-year anniversary of Hagler’s 1981 rematch with Vito Antuofermo at the Boston Garden. As the new champion, Hagler was making the second defense of the world title he won in 1980 from Alan Minter. Hagler’s first shot at the title came in 1979 against Antuofermo in Las Vegas and was ruled a draw. The rematch was a mismatch.

The unveiling, scheduled for Thursday June 13 at 11 am, will also fall on the 31-year anniversary of Hagler’s 1993 induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, NY. Will thousands show up to celebrate like they did when another Brockton boxer was remembered?

Back in 2012, when a 22-foot-tall Rocky Marciano statue was put up by the WBC, many asked why Hagler didn’t also have a statue in Brockton and would he ever get one? The answer is yes.

Somebody finally did something for Hagler. Before he died in 2023, longtime Marciano family friend Charlie Tartaglia told me the reason he put up a bronze plaque for Hagler at Massasoit College with his own money was because as he put it, “Nobody ever did nothin’ for Hagler.”

Brockton state representative Gerry Cassidy secured the $150,000 needed from the state to build and maintain the long overdue statue in tribute to Hagler who died in 2021 at the age of 66.

Hagler’s new sculpture will be on display approximately two miles away from Rocky’s. It won’t be as tall as Marciano’s towering memorial but that’s fine, Rocky was a heavyweight while Marvin was a middleweight.

“This testament to a true hometown sports and community icon will be a permanent monument to one of the greatest champions from our ‘City of Champions,’” said Brockton Mayor Robert F. Sullivan in a public statement announcing the marvelous news.

The legendary physique of Hagler in his prime is befitting of a likeness commemorating it. Somebody on Facebook wrote, “I guarantee his jaw and muscles were stronger than his statue is going to be.” Another Facebooker wrote, “A fitting tribute to a boxing great gone too soon.”

Hagler reigned as middleweight champion of the world from 1980 to 1987 and during this time he carved out a reputation as one of the greatest middleweight champions in the history of boxing. Hagler was a member of the “Four Kings” which also included Sugar Ray Leonard, Thomas “The Hitman” Hearns and Roberto Duran. Hagler beat Duran and Hearns but lost to Leonard.

One of the reasons it took so long for Hagler to be honored in this way is that despite his greatness in the boxing ring, Hagler had another reputation in Brockton and that was as somebody with the capacity for violence against women, most notably his ex-wife Bertha.

Domestic incidents between the pair were common and in her complaint against Hagler, Bertha alleged that she lived in fear of Marvin; that he put his hands on her and threw a large rock at her car. Regardless of all this, Brocktonians are happy and excited to see Hagler and his surviving family finally get what’s coming to him even if it will come three years after Hagler passed away.

Still, not everyone in the City of Champions is so pleased with the planned placement of the new statue. As mentioned, the Hagler memorial will be located a couple miles away from Marciano’s.

“Hagler’s statue belongs at Brockton High School,” says Mark Casieri, owner and caretaker of Rocky Marciano’s childhood home located at 168 Dover Street. Casieri knows a thing or two about Brockton boxing. “It belongs there alongside Rocky’s statue so that the youth coming up through the school system are able to know the sports heroes that came out of Brockton.”

Brockton High School has been in the news recently but for all the wrong reasons. Violence and debauchery at the high school has gotten so bad that politicians considered bringing in military units of the National Guard to quell the unprecedented unrest. It’s ironic but Brockton has become like Newark, NJ, the city that Hagler’s mother moved him away from to protect him.

As a young middleweight just starting out as a professional fighter, Hagler fought nine of his early bouts at the Brockton High School gym including his pro debut against Terry Ryan in 1973.

For the record, I reached out to Brodin Studios for some information about the statue (its official height and weight? What fight is the action poise from?) but they are playing it very close to the chest, saying only what an honor it was to build it for Hagler and the entire Brockton community.

The Marvelous One is finally getting his statue in the City of Champions. Better late than never.

Photo insert: Marvin Marvin and Vito Antuofermo (undated; circa 2010)

*** Boxing Writer Jeffrey Freeman grew up in the City of Champions, Brockton, Massachusetts from 1973 to 1987, during the Marvelous career of Marvin Hagler. JFree then lived in Lowell, Mass during the best years of Irish Micky Ward’s illustrious career. A former member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and a Bernie Award Winner in the Category of Feature Story Under 1500 Words, Freeman Covers Boxing for the Sweet Science in New England.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Fury vs. Usyk: Who Wins and Why? – The Official TSS Prediction Page

The heavyweight division, it has been said, is the engine that drives the sport of boxing. By this measure, Saturday’s match in Saudi Arabia between Tyson Fury and Oleksandr Usyk is the most important fight in decades.

Whenever a very big fight comes down the pike – assuming the odds are not too lopsided – we call upon our fine community of wordsmiths to get their thoughts. The participants in the poll are listed alphabetically.

—

Simply put size matters. Usyk has never fought anyone that weighed more than 225 pounds and given Fury’s recent history it seems safe to assume he should tip the scales north of 260. Eleven years ago, Fury fought another former cruiserweight champion in Steve Cunningham. Cunningham’s speed gave Fury problems early and Fury was even knocked down. But Fury used his size and weight to lean on Cunningham draining him of all his energy. Eventually a badly fatigued Cunningham was knocked out by Fury. I see something happening when Fury faces Usyk. Usyk has success early and maybe even scores a knockdown or two. But Fury leans on Usyk and uses that weight advantage to slowly wear down the smaller man. FURY TKO 10. – MATT ANDRZEJEWSKI

After a lackluster and controversial split decision win over Francis Ngannou, Fury looks fit as a fiddle and should handle the six-inch shorter Usyk by keeping his distance and landing more than enough big blows. In a fight filled with drama and excitement, it’s FURY by unanimous decision. – RICK ASSAD

Fury’s jab and straight right vs. Usyk’s straight left and right hook (think Cotto vs. Pacquiao), whichever two-punch combination is more effective will decide who controls the range and pace. I believe Usyk’s straight left along with his southpaw stance and movement will give Fury trouble, but Usyk doesn’t attack like other smaller heavyweights to the body (i.e. Tyson/Frazier). Like Lomachenko, he uses his footwork to get inside, which will give him enough moments to make a focused and in-shape Fury take it to another level. Fury also isn’t a big body puncher, but he will use his size to lean on Usyk after he lands clean shots to wear Usyk down and gain control of the fight. FURY by decision. – LUIS CORTES III

Oleksandr Usyk is a good little man but he’s in way over his head against a well-trained Tyson Fury who looks to be treating this fight with the respect it deserves. Usyk will puzzle Fury for a few rounds but once Tyson makes his adjustments, he will bring his superior size and power to bear on the smaller fighter, wearing him out to the body and grinding him down late. I pick FURY by TKO in the championship rounds. Usyk will be on his feet when the fight is stopped but nobody will be crying foul about it. – JEFFREY FREEMAN

FURY by stoppage late. He’ll be in condition this time (unlike the Ngannou debacle). And an in-shape Fury boxes well enough and is too big and strong for Usyk to deal with. – THOMAS HAUSER

There’s always a chance that a fight will be stopped on cuts. Of the two, the Gypsy King would seem to be more prone to this unfortunate happenstance. He overcame a terrible gash over his right eye to upend Swedish southpaw Otto Wallin and it was a cut over his right eye during a sparring session – a cut that reportedly required extensive stitching — that pushed back this fight from its originally scheduled date of Feb. 17. Since this fight has a rematch clause, the ring physician may feel less pressure to allow the fight to continue against his better judgment if it boils down to this. Regardless, USYK has lost fewer rounds as a pro and it’s easy to envision the Ukrainian banking enough rounds to stave off a late rally by Fury to cop the decision. – ARNE LANG

A lot of ink has been shed on the cut Tyson Fury suffered in sparring causing a postponement of this fight to this coming Saturday; it’s Tyson Fury’s elbows that interest me though. Fury fought in terrible pain in his third contest against Deontay Wilder in 2021, taking cortisone injections in both elbows prior to this fight. Wilder actually outjabbed Fury early and Fury threw three or fewer jabs in seven of the eleven rounds. Since, he has been inactive (only three fights since his late 2021 defeat of Wilder), unimpressive (especially against novice Francis Ngannou last year) and irrelevant (the world needed Chisora III like it needs more inflation). In short, this fight, which once seemed so clear cut to me, will now be decided by intangibles. Fury looks sleek, I’m interested to see his weight. Over 265lbs and he’s struggling to get the jab working and will be here to maul a fleet-footed Usyk. Under and he thinks his elbows are right and he will look to control the smaller man with his range. Based on the videos team Fury have been releasing, I’ll go for Fury to dominate until his stamina starts to slide at which point, Usyk will take over – I think that will be late enough for Fury to get home with a decision win. But nothing would surprise me now. – MATT McGRAIN

Since his high profile wins over Deontay Wilder, madhatter Tyson Fury has carried himself like a dilettante (admittedly, not the first time he has been guilty of that charge in his erratic career) and the effects showed last year against Francis Ngannou, a boxing newbie who nearly (and risibly) secured a place in prizefighting lore next to Buster Douglas. Fury will find his usual advantages—size, footwork, counter punching—negated by Oleksandr Usyk, who, despite being a converted cruiserweight, has proven he can not only outthink his opponents but outwork them as well. USYK via Split Decision – SEAN NAM

FURY uses size alone for a UD 12, with little drama barring a cut. Unless the distractions of Fury’s celebrity lifestyle have eroded his mauling focus (the wake-up call against Ngannou probably remedied that), I can’t see how Usyk can win this though he’s proved me wrong before. Fury’s mobility makes it very doubtful Usyk will be able to get in and out unscathed to score like he did against Joshua or Dubois, and even more unlikely he can outgun Fury toe to toe. Still, Usyk has perfected his southpaw style into a puzzle nobody has solved yet so Fury might have some early problems. — PHIL WOOLEVER

Editor’s Note: It’s a fair guess that Fury vs. Usyk will be the most heavily bet fight of all time, surpassing Mayweather-Pacquiao. As a rule, fights in the “pick-‘em” range attract the most action. At mid-week, although the action was tilting toward Fury, “11/10 and take your pick” was still readily available. In fact, at some houses, the action is so well-balanced that the operator reduced his vigorish (i.e., the house commission assuming balanced action), going from a 20-cent to a 10-cent line, confident that he could not lose.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

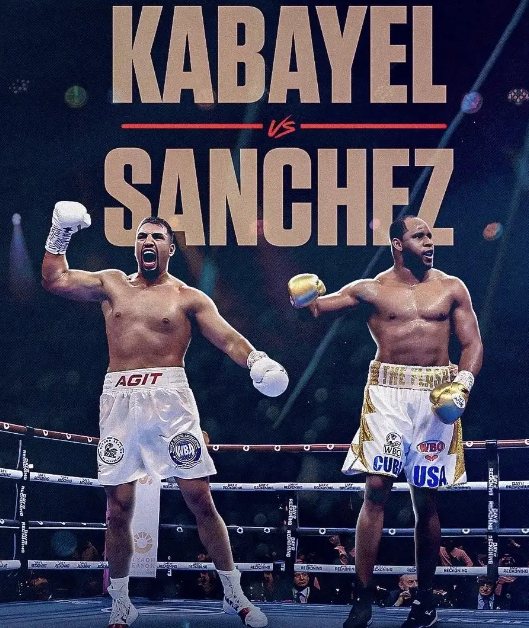

Will Kabayel vs Sanchez Prove to be the Best Heavyweight Fight This Weekend?

Will Kabayel vs Sanchez Prove to be the Best Heavyweight Fight This Weekend?

Tyson Fury and Oleksandr Usyk meet on Saturday at Kingdom Arena in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Barring a draw, the match will produce the first undisputed heavyweight champion in the four-belt era.

The bout is supported by an outstanding undercard that includes a heavyweight fight that may prove to be more entertaining than the headline attraction.

On paper, there’s little to separate Agit Kabayel and Frank Sanchez. Both are listed at 31 years old, arguably the optimal age for a heavyweight. Both are 24-0. Sanchez has 17 knockouts to his credit; one more than Kabayel. Both appeared in this ring on Dec. 23, so neither in theory has any rust.

Kabayel, born in Germany of Kurdish descent, upset the odds in a career-best performance, stopping Arslanbek Makhmudov in the fourth round. Heading in, the “Russian Lion,” who carried 262 pounds on his six-foot-six frame, was 18-0 with 17 knockouts, of which 12 came in the opening round.

This was no fluke knockout. Kabayal chopped him down, scoring three knockdowns with body punches until the fight was waived off.

On the same bill, Frank Sanchez scored a seventh-round stoppage of New Zealand’s Junior Fa. This fight took a long time to heat up, but when it did, the kiwi was outclassed.

Of the two, Sanchez is the smoother boxer. His signature win was a comprehensive 10-round decision over otherwise undefeated Efe Ajagba. He’s also taller than Kabayel who is generously listed at six-foot-three.

As an amateur, Sanchez was purportedly 214-6. And although that record was manufactured from thin air, there’s no doubt that the Cuban Flash, whatever his true amateur record (boxrec has it 43-12), was top-shelf in a pod replete with some of the world’s top amateurs.

By contrast, Agit Kabayel reportedly had only five amateur fights before turning pro.

Sanchez has been training at Eddy Reynoso’s compound in San Diego. That’s another “plus” for him on the handicapping checklist. However, Kabayel is the harder puncher and we suspect that Sanchez is actually older than his listed age, a common deception among Cuban athletes after they leave the island.

Kabayel will have more rooters, which may or may not affect the betting marketplace. His style is more fan-friendly and he’s had a harder road to get to this point in his career. After upsetting Derek Chisora in 2017, he fought only once in each of the next five years, a slowdown related to Covid, managerial issues, and fights falling out.

—

The WBC has sanctioned Kabayel vs Sanchez as an eliminator with the winner next in line to fight the winner of Usyk vs. Fury. But don’t hold your breath. The Fury-Usyk fight has a rematch clause and if the Gypsy King wins, Anthony Joshua will almost certainly leapfrog to the head of the queue.

History informs us that whoever wins the Usyk-Fury fight likely won’t stay undisputed for very long. One or more of the organizations will strip the title-holder for failing to fulfill his mandatory.

That’s what happened to Lennox Lewis after he won his rematch with Evander Holyfield. Nine months later, after Lewis demolished Michael Grant and Frans Botha, Holyfield won the vacant WBA world heavyweight title with a narrow decision over John Ruiz in the first of their three meetings.

In boxing, the more things change, the more they remain the same.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoIn a Massive Upset, Dakota Linger TKOs Kurt Scoby on a Friday Night in Atlanta

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoHaney-Garcia Redux with the Focus on Harvey Dock

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

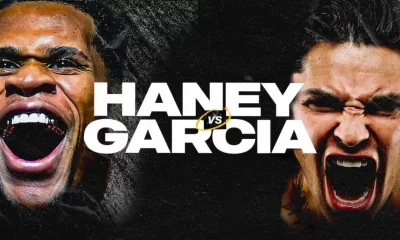

Featured Articles4 weeks agoIn a Shocker, Ryan Garcia Confounds the Experts and Upsets Devin Haney

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 281: The Devin Haney and Ryan Garcia Show

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRamirez Outpoints Barthelemy and Vergil Ortiz Scores Another Fast KO in Fresno

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoA Closer Look at Weslaco ‘Heartbreaker’ Brandon Figueroa and an Early Peek at Inoue vs Nery

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoHaney and Garcia: Bipolar Opposites

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRamon Cardenas Channels Micky Ward and KOs Eduardo Ramirez on ProBox