Articles of 2009

Brute, Part XV: Write Well For Us, Huh?

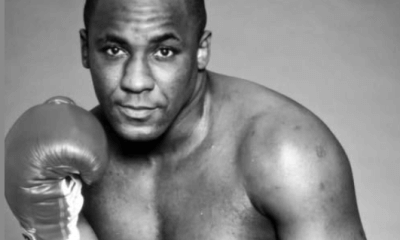

he forthcoming book “Brute” follows two Sacramento boxers: Mike Simms, a cruiserweight who trained with the Olympic team in 2000, who when I found him had lost five successive fights; and Stan Martyniouk, a young, Estonian-born featherweight, who when I found him had just fought and won his professional debut by decision, despite breaking his right hand in the first round.

Over the next few months I look forward to sharing the stories of these two fighters with the readers of the Sweet Science, and I look forward to hearing from any and all of you. –KS

In the lobby of the Red Lion, at 7:30 in the evening, I found that I was not as nervous as I had been for the last fight. In May I was as anxious as if I’d been expected in the ring at eight and had skipped my last two weeks in the gym. Now I felt a little less the stranger. This time I had a ticket, and I hadn’t had to pay for it. I went through the security line and into the ballroom, and did not even look for my seat. The bar, I knew from the last fight, was the best place to see the ring.

I put my pad down on the bar and asked the bartender for a Diet Coke. While I waited for the drink I took a few notes and noticed, as I wrote, that a man was standing at my right shoulder. He seemed as if he wanted to ask me something, but was concerned about interrupting me. “Give me just a moment,” I said.

“I didn’t want to bother you,” he said.

The bartender put down my soda and when I tried to pay her she refused, so I left her a tip and turned to my subject. I could not place him, but perhaps we’d spoken at the fight in May. “What’s up, man?” I said.

“You write for The Sweet Science, right?”

“I do indeed,” I said.

“I read your article after we talked last time.” That confirmed that we had met, though I could not place him in that chaotic evening. “What’s your name again?” he asked.

“Kaelan,” I said.

“Kaelan Smith, or something.”

“That’s right.”

“You’re always taking notes,” he said.

“There’s a lot to take notes on,” I said.

“I should probably do that. I sometimes write for 15rounds.com. Usually I just come here to get drunk.” He had what I assumed was a rum and Coke. The ice in it was hardly melted, though the plastic cup was almost empty, and I figured that he wouldn’t change his routine for this fight. I decided that I should get some fresh air on the pool patio before the punching began, and I shook the hand of my admirer, realizing as I was leaving the ballroom that I’d forgotten to ask his name.

On my way out I saw Nasser Niavaroni near the exit, scowling with his arms crossed and growling into his phone. But when he saw me he uncoiled his arms and waved. “How you doing?” he said.

“I’m well,” I said. I was growing comfortable with the knowledge that in May he hadn’t taken me seriously because, amongst other professional shortcomings, I’d walked into his gym wearing a Red Sox hat and effectively asked him for one hundred dollars. To be bitter about his discounting me was therefore shortsighted and petty. And since I’d found through Mark Wilkie another way to watch the fights for free, I was beginning to look on him differently. With the sort of noble but misdirected audacity Mondale had demonstrated when picking Ferraro to run on his ticket, Niavaroni was trying to revive the boxing culture in Sacramento. For Mondale it was the popularity of the incumbents that proved insurmountable, whereas for Niavaroni it was the celebrity of the challenger—the brutal charm of mixed martial arts—but regardless I was grateful for his enthusiasm.

I didn’t recognize anyone on the patio, so I didn’t stay long. When I got back to the bar I noticed a man who’d been at the weigh-ins the night before. He was a friend of Gerrell’s, and I went up to say hello and to see if the White Tigers had arrived. As I approached him he unfurled a black “Stan the Man” t-shirt and slipped it over his head. Why he hadn’t worn it in I couldn’t imagine. Perhaps he’d been out to dinner before and was afraid he might encounter the white stallion Terrance Jett had ridden up from Las Vegas, but it seemed more likely that the Red Lion ballroom was a more dangerous venue for partisans, even if half the card was from the central valley.

He saw me, and at the same moment his phone rang. He answered it, spoke briefly into it, and then hung up. “Derek?” I asked.

He said that yes, man, we’d met the night before. “Gerrell just pulled in,” he added, looking at his phone to indicate the source of this information. “You write a lot, don’t you?”

“Must take notes,” I said. It was true, I’d found, that in order to write well about an event I had to take copious notes. But I was also beginning to realize that by constantly writing what people said on my page (I was writing as I talked with Derek) I was setting myself apart. It made people wary of me, and at the same time I was acutely aware that they were trying to impress me. As if to punctuate this thought, a young Asian man in a brown blazer who’d been standing in our vicinity came over and put his hand on my shoulder.

“Write well for us, huh?” he said. I promised him that I would. I was, I knew, sometimes making fools of the people around me by cataloguing their words and gestures, but I was also making heroes of some. For instance, I wanted to convey to whatever audience I’d garnered that Stan Martyniouk was a fine, young boxer with great promise, because that was the impression he’d given me. If I mocked Nasser Niavaroni, it was only because he had been inconsistent and duplicitous. Now that he was revising the impression I had of him, I felt it necessary to revise my portrayal.

The announcer stepped into the ring and took the microphone. “The first bout of the evening,” he began, “will start in just five minutes.” The crowd, which had quieted for the sentence, did not display any unified interest in the announcement. Most of them continued talking with the men they hoped to impress with their knowledge of boxing, or to the women whom they’d brought to impress those same men. It should be said that fight fans are still predominantly male despite the relatively recent burgeoning of women’s boxing. Laila Ali is a great boxer, but she is famous first for having issued from Muhammed Ali, second for having danced with the stars, and only third for having punched other ladies in the face. It is therefore a certain type of woman who comes to a fight, the sort that browns under a lecherous glare but does not burn, who wears a very short skirt and large earrings, or in the case of the round girls, often no skirt at all.

While the crowd was forgetting the imminent fight, I saw Mehrad and Gerrell making their way through the horde. They saw Derek first and said hello to him. Then I shook hands with both of them and apologized that I hadn’t worn my “Stan the Man” shirt. “But I did wear black in homage to the ‘Stan the Man’ shirt,” I said. Both Gerrell and Mehrad seemed pleased, although Mehrad appeared nervous. Looking at his face I realized—and I say realized because until that point it really hadn’t occurred to me—that Stan might not win his fight with Terrance Jett. If a boxer is going to lose early in his career, it’s best that he lose his first bout. History forgives and sentimentality prefers a disastrous opening night if the subsequent performances inspire a standing ovation. The nerves accompanying a debut can erase a decade of training, so as a fan it is easy to absolve a young boxer for forgetting to lead with his jab, or failing to disengage effectively after a dance. But what can you say of the man who loses his fourth fight? A manager can over-match a potentially great boxer in his first fight or his tenth. But if a boxer loses that fourth fight (or the third or the fifth) it becomes increasingly difficult to under-match him. It is course par étapes that a handler races his horse against the sort of horses that will encourage growth without stunting it. But if a fighter gets beaten while his career is flowering, he risks becoming the tester and not the tested. Perhaps the most tragic fate for a boxer—worse even than losing his first five and retiring—is to win three and lose one and get relegated to that undercard, fighting four- and six-rounders, and leaving the hall each night before the main event.

As this was now on my mind, I assumed Mehrad was suffering similar anxieties. But he was trying to smile through it all, and I was too, and the White Tigers, now a veritable pride (I’m confusing my cats), looked up at the ring. I’d received an email about the fight card from Mark Wilkie, but had discovered that at the Red Lion the pre-determined sequence of the bouts was more of suggestion than an order. Therefore I didn’t know whom the man was with the towel over his shoulders that had just ducked through the ropes. Neither, from their disimpassioned response, did the crowd.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoA Night of Mismatches Turns Topsy-Turvy at Mandalay Bay; Resendiz Shocks Plant

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering the Under-Appreciated “Body Snatcher” Mike McCallum, a Consummate Pro

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books