Articles of 2009

Joey Gamache's Final Fight, For Truth And Justice, Part I

“There’s no tomorrow for me if I lose. Arturo Gatti’s not an easy fight. He turns everything into a war. I know this is the final chapter of my career.” –Joey Gamache before his last in-ring fight, on Feb. 26, 2000, against Arturo Gatti

Joey Gamache was speaking figuratively when he shared his mindset leading up to his bout against the Human Highlight Machine, boxing’s premier blood and guts warrior, on the undercard of the Oscar De La Hoya-Derrell Coley main event at Madison Square Garden. When he spoke of there being “no tomorrow,” he understand that his professional window was open only a sliver, and that at age 33, after 58 times climbing up those stairs, and into that ring, soon enough he’d need to find something else to fill his days, and pay the bills.

Soon enough, the third generation pugilist knew, he could dive into his drywall business with all his energies. But not yet. There was a comeback to attend to, one last thrust at the upper reaches of the most dangerous game. And a win over Gatti, the pugilistic darling of HBO who epitomized the unfathomable but laudable refusal to quit in the face of a hailstorm of punishment, would propel the Maine native up several rungs on a new ladder, the junior welterweight class. Gatti, like Gamache, had been sipping from the bitter chalice of defeat lately, not the sweet nectar of victory. A loss to Angel Manfredy, two defeats to Ivan Robinson, and he’d deposited another bucket of blood on the canvas in recent defeats. Gatti was compromised, Gamache felt, and ripe for a takedown.

He didn’t feel impregnable after going into the office of Lou DiBella at HBO, and begging for the Gatti fight months before, but he believed in his ability, in his ring generalship, that his style was right to prolong Gatti’s losing streak. Gamache knew full well that Gatti had an in-ring mindset that would make him a bad bet to try and save if he were, say, caught in a riptide. Most fighters, even those guys known for being willing to “go out on their shield,” have a mechanism inside them that kicks in, which recognizes when the current is too strong. They take a knee, send a subtle signal that their cornerman picks up on, so the chief second can throw in the towel, and save their man from having to submit himself. Think of that mechanism as a life preserver. Gatti was prone to grabbing on to that life preserver, and chucking it aside. His fierce pride, mixed with a desire to give the customers what they came for, even if it was to his long-term neurological detriment, meant Gatti always tossed the life preserver to the side.

There will be trading, there likely will be blood, Gamache knew, but he expected that he’d get the better of the trades, with his superior technique, and that more of the blood in the ring at Madison Square Garden would be Gatti’s.

Gamache’s dad, Joe Sr, and his dad, Elmo, had boxed in Lewiston, Maine and thereabouts. They were amateurs, but the third Gamache hitter showed more acumen. He hit a gym on the recommendation of dad, who suggested that boxing workouts might strengthen his arms for Little League. He excelled, stuck with it, and powered through the New England Golden Gloves, on the way to a bronze medal at the 1984 Olympic trials. On the way, he never turned down a fight. At age 12, at one tourney with somewhat lax regulations, he fought a twentysomething sailor, and stopped him with a body shot. He was more boxer than slugger, and he reminded the man who oversaw the vast majority of his pro career, Brooklyn-born advisor Johnny Bos, of Caucasian craftsmen like Joey Archer, Billy Conn, Paul Pender, Willie Pep. Gamache had no problem with a little toe to toe tango, so he definitely had a streak of that caveman in him that can be so helpful when the guy across from you is clubbing you, you’re seeing stars, and a lesser man hits the deck and lets the count reach ten. But you really wouldn’t know it when you interact with him. The opposite of brash, Gamache stands out for his humility and congeniality in a sport that actually boasts far more of these sweet tempered types than the uninformed might know. Gamache is quick to break into a shy grin, most of the time, and it is next to impossible to get him to so much as critique anyone, even if that anyone has done him wrong.

That humility, that decency was apparent when Gamache lost his first bout as a pro. In his first WBA lightweight title defense, he took on 40-3-1 Tony Lopez in Portland, Maine. The action in Oct. 1992 was tight, though Gamache’s eyes were both swollen and discolored. In the 11th, though, “The Tiger” pounced with combos that forced the ref to halt the bout. After, Gamache gave the Sacramento fighter his due.

“He beat me legitimately,” said the now 29-1 Gamache. “No excuses. He's a strong, courageous fighter and he came to my hometown and beat me legitimately.”

Gamache put together seven straight wins after that, as Bos steered him to another title crack, this one against Orzubek Nazarov, in Dec. 1994. The rugged Russian entered the ring in Cumberland, Maine at 19-0, with 15 stops. He broke Gamache’s nose in the first round with a hook, and bore down in the second. A left hook sent Joey down, and soon after, a flurry stopped his night for good, at 2:50 of round two. Again,Gamache gave the victor full credit.

“I feel like I never got started,” said Gamache. “But what can you do? Nazarov had a lot to do with that. He caught me with a good shot and he was exceptionally strong. I never really had a chance. He came in rocking and socking. I'd fire something and he'd come right back. That's how it goes. Tonight, I got beat by a better man.” He got beaten at the box office, too. He was working off the gate at the arena, and the take that night wasn’t enough to pay off Nazarov, and give himself a healthy cut. Or, actually, any cut at all. The cruelest game can be punishing in so many ways, but taking a whupping hurts that much more when you can’t even make the mortgage payment the month after you got worked over.

Gamache absorbed maybe an even crueler slap-down from his community, his people. The adoring throngs who longed to shake his hand, to insinuate themselves into his world, who eagerly bought first-class tix on the Gamache bandwagon on his ascent, just as eagerly disembarked the ‘wagon when Joey disappointed them. The textile mills had shut down, leaving too many of the 35,000 in Lewiston without work, and with a need for good news, and heroes to look up to, to help them forget their plight. Maybe they invested too much into Maine’s best all-time boxer, identified too much with Joey, so when he lost, they took the defeats personally. Instead of helping to build him back up, and bolster his dented psyche, many Mainers avoided him, and stopped buying tickets to his fight. Gamache isn’t one of these brash hitters who can shut everything out. He has a sensitive side, and he took the exodus hard. Were they calling him a fraud, a fake, to his face? Not so much; the bandwagon crew felt jilted, not suicidal. But he heard whispers, read the glances, saw the sneers of disgust. Relations with his own family suffered. His dad and Bos beefed frequently, and Joey was caught in the middle. He tried not to take sides—but this is an impossibility when you are silently asked to choose between blood and other. Joey and Bos saw other people for awhile, but got back together, for one more run to the top of the mountain.

Julio Cesar Chavez had taken on the second loss of his career four months before, to Oscar De La Hoya. The assassin from Culiacan needed to dust himself off, get back on the horse, and hit the trail again…and Bos suggested Gamache as the tester, for a damn good fee, $250,000. Both men had seen better days, but neither wanted to relinquish their spot, as they saw it, in the sweet science realm. In Anaheim, California, they would square off, battling each other, and fighting the little voice in the back of their head that is so tactless, the one that informs you that you are not wine, you are not getting better with age. Both would be trying to counter the effects of erosion from aging with a reliance on smarter strategy and pacing. One man would look the worse for wear after, one of them would reach for one of the games’ saddest symbols: the sunglasses, to be worn at night, indoors, to mask the effects of a hard rain of punches.

END, PART 1

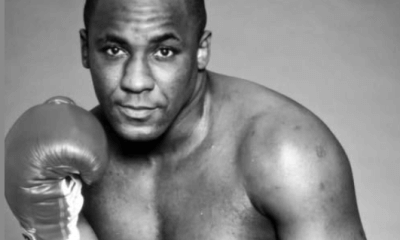

*photo from 1992; courtesy Johnny Bos

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoA Night of Mismatches Turns Topsy-Turvy at Mandalay Bay; Resendiz Shocks Plant

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering the Under-Appreciated “Body Snatcher” Mike McCallum, a Consummate Pro

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books