Articles of 2009

THE KIMBALL CHRONICLES: WHAT'S UP WITH THIS DOC? Ali-Holmes

Earlier this year, ESPN revealed plans to simultaneously celebrate its 30th anniversary and expand its cultural horizons with a season-long film festival that would showcase the work of some of the more acclaimed filmmakers of our time — including but not limited to the likes of Barry Levinson, Ron Shelton, Barbara Koppel, and Albert Maysles.

The “30 on 30” series opened earlier this month with Peter Berg's “King's Ransom,” an examination of the ripple effect throughout the National Hockey League of the 1988 trade that brought Wayne Gretzky, the best player of his era, from Winnipeg to Hollywood. Last week the network premiered its second installment, Levinson's “The Band that Wouldn't Die,” in which the man who made “Diner” looks back at the Colts' 1984 abandonment of Baltimore, a bittersweet paean which affords Levinson one more opportunity to kick Robert Irsay up and down The Block.

The initial airing of the third film, “Small Potatoes: Who Killed the USFL?”, was scheduled for Oct. 20. The work of Mike (“The Bronx is Burning”) Tollin, “Small Potatoes” has already stirred up its share of controversy, thanks to Donald Trump, whose name is the answer to the question asked in the subtitle.

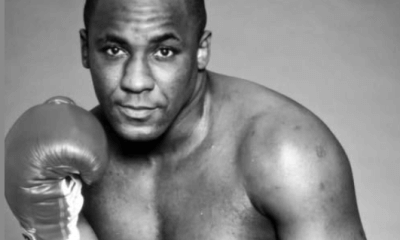

The network which built its early success on live boxing turns its attention to the Sweet Science next week, with the debut of Maysles' “Muhammad and Larry,” a quasi-documentary centered around Muhammad Ali's doomed attempt to regain the heavyweight title in what proved to be the penultimate fight of his 61-bout career.

The Maysles Brothers had been granted virtually unlimited access to the camps of both champion and challenger in the weeks and months preceding the fight at Caesars Palace, but for various reasons (chiefly rights issues concerning the actual fight footage) the footage had remained dormant for the better part of the past three decades. Kick-started by the ESPN agreement, Maysles and his new filmmaking partner Brad Kaplan (David Maysles died in 1987) re-interviewed many of the surviving cast of characters — Holmes, along with Angelo Dundee, Dr. Ferdie Pacheco, Gene Kilroy, and Wali Muhammad from the opposing camp, but not, conspicuously, Ali himself — and augmented their recollections with those of a number of boxing writers in revisiting what had by almost any standard been an incredibly depressing experience for everyone concerned. Including the guy who won the fight.

* * *

I was in London for the Marvelous Marvin Hagler-Alan Minter fight the previous weekend, and was consequently one of the few boxing writers in America who wasn't at Caesars Palace on the night of Oct. 2, 1980.

When we'd talked about it over breakfast a few days before Hagler's fight, Goody Petronelli seemed to think Holmes-Ali was such a foregone conclusion that he wondered why they were fighting at all.

“If everything's right,” he said, “I don't see how Ali can win.”

Even though it loomed a colossal mismatch going in, I was curious enough about seeing it that I'd made sure I'd get home in plenty of time to watch the closed-circuit telecast. Rip Valenti was running a live card at the old Boston Garden that night, followed by the telecast of the fight from Vegas, and my flight to Boston would get me back in plenty of time for both.

Of course, those things don't always work out as planned. Europe had been particularly affected by the worldwide fuel shortage, so the Aer Lingus plane that took off from Dublin first backtracked to Scotland, and re-fueled at Prestwick. From there came the obligatory stopover at Shannon, where the plane was emptied so the passengers would shop. By the time I actually landed, it was already dark. A cousin then working at Logan airport had made arrangements to whisk me through customs and I jumped in a taxi for the Garden, arriving with only minutes to spare before Ali's fight.

We watched from the press room, where they'd set up a few folding chairs. I was joined by the venerable New York Times columnist Red Smith, who'd come up from his summer home on Martha's Vineyard with his friend Eliot Norton, the drama critic at my newspaper, the Boston Herald. At the time of the Holmes-Ali fight, Red had a bit over a year to live, and at 77, Eliot was two years older than Red was.

Smith had never been what you'd call a huge Ali fan, and in a column a few days earlier he'd expressed reservations similar to Goody's, all of which were borne out that evening. Ali started with nothing and had less as each round passed. Eliot must have felt as if he were covering some sort of Shakespearean tragedy; it was that sad and pitiful. None of us could understand why Richard Greene was allowing it to go on, and why in the absence of any intervention from the referee, Angelo Dundee didn't stop it himself.

Finally, at the end of ten, Dundee called Greene over to the corner and asked him to stop it. This in turn produced a beef with Bundini Brown, who tried to overrule Angelo, but Dundee reminded the referee that he was the chief second, and he won that argument. Bundini almost immediately burst into tears, and by the time they got him on camera, Larry Holmes was crying, too.

It was a story we all knew we'd have to write one day, but I was pretty glad I hadn't been there that night. As it turned out, it was a temporary reprieve. I was there the next year when Ali fought Trevor Berbick in the Bahamas, so 14 months later I had to write it anyway.

* * *

Albert and David Maysles had pioneered the documentary-as-art-form, going back to the days of “Primary” (1960) and their 1975 classic “Grey Gardens.” In 1970 they had set out to make the first great rock-n-roll epic in “Gimme Shelter,” and wound up producing the first commercially viable snuff film when they included footage of the Hell's Angels killing a spectator at the Altamont Festival.

In addition to the aforementioned rights difficulties, the Maysles had another problem with “Muhammad and Larry” 30 years ago, which is that the wrong guy won. Whether they actually believed Ali had a chance, or whether they thought that Holmes would emerge from that fight with an enhanced image isn't clear, but the fact is that what happened that night in Vegas seemed so obscene that distributors were convinced, probably correctly, that nobody wanted to look at it again.

Barely half of the hour-long ESPN version is from the original footage, and some of the latter-day observations seem frankly self-serving. The guy who comes off best, ironically, is Pacheco, who had walked away from Ali's corner in 1977 when his retirement advice went unheeded.

Ali had lost and then regained the title for the third time by outpointing Leon Spinks, and then announced his retirement following his final win. The heavyweight title had been divided, with John Tate and then Mike Weaver holding the WBA version. Holmes, who as a nascent pro had been one of Ali's regular sparring partners, had won the WBC version by beating Ken Norton. (The latter remains the only heavyweight “champion” in history who lost the only three title bouts in which he participated.)

The film contrasts Holmes' storefront training camp in Easton with what looks like a 24/7 zoo in Deer Lake, where Ali seems to be more interested in catering to the tourists than in actual training. (A very young Tim Witherspoon, who sparred with Ali for Holmes, offers some interesting observations about his mentor's regimen, or lack of one.)

In the run-up to the Holmes fight, Ali had grown a mustache (he did shave it off when he got to Vegas), and referred to himself as “Dark Gable.” Since this was pretty much the only time he sported facial hair, it's almost like watching a stranger who vaguely resembles Ali speak his lines.

And while the physical problems that would overtake him a few years later hadn't fully manifested themselves, his speech in 1979 was markedly different from what it had been a decade earlier that one can only wonder why no one save Pacheco seems to have noticed.

Early in the film Holmes recalls being approached by a woman — a total stranger — whose first words were “I hate you!” His crime, of course, had been beating Ali. At that point he began to realize that just as his image had suffered because he was considered an unworthy successor, he would henceforth be blamed in some quarters for his part in turning Ali into what he has become today.

Some would argue that this course had already been set. Pacheco, who describes the Holmes fight as “an abomination,” may have gotten carried away with himself when he says that everyone connected with it should have been put in jail, but he, and others, argue persuasively that it probably shouldn't have happened.

With rumors, some of them no doubt emanating from Pacheco, that Ali was evincing symptoms of mental and physical deterioration, the Nevada State Athletic Commission ordered a battery of tests performed by the Mayo Clinic before they would reissue his license. Ali's biographer Thomas Hauser points out that the Mayo tests revealed that Ali had experienced difficulty in performing normally rudimentary functions like touching the tip of his nose, and hopping on cue. These might have been considered clear warning signs, but Nevada issued the license anyway, and for reasons best known to itself, the commission declined to make the Mayo test results public.

In footage from a round-table discussion conducted at the Versailles restaurant in Las Vegas last March for the Maysles film, John Schulian — my Library of America anthology co-editor who had covered Holmes-Ali as a columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times — notes that the Mayo Clinic tests had showed evidence of irregularity in Ali's brain function.

“They did not!” former Ali aide Gene Kilroy nearly leaps across the table as he explodes. “All it showed was that he had some problems with short-term memory loss.”

Since the film lets that pass without comment, it is left to us to break the news to Kilroy: Short term memory loss is usually an early indicator of frontal-lobe brain damage.

In training, Ali probably compounded the problem when he let his sparring partners hammer away at him in the belief that it would toughen him up for the ordeal he expected, but as Pacheco points out, one's kidneys do not bounce back from such trauma. Then, in the weeks before the fight, on the advice of some crackpot doctor and with no apparent medical foundation, Ali received a prescription for thyroid supplements and began using the medicine like so much candy.

Holmes was going to win this fight anyway, but the film effectively makes the point that Ali's chances decreased at almost every turn. Participating in a panel discussion (along with Maysles, Kaplan, Pete Hamill, and ESPN's Jeremy Schaap) after Monday night's New York screening, Holmes complained that by pointing all these things out, the film tended to cheapen his victory by making it appear that Ali had beaten himself.

Even during his long and estimable reign as champion Holmes was always touchy about living in Ali's shadow, and that has apparently not abated with time. While he didn't specifically complain that the film's title has the winner's and loser's names in reverse order, he might have. And, interviewed in Easton this year, Larry's long-suffering better half, wife Diane, takes it upon herself to complain that her husband never got his just do.

“It's like he fell of the face of the earth,” she tells the unseen interviewer. “Look how long it took you to get here!”

As what had become a ritual beating that night wore on, Holmes on several occasions seemed to be imploring Greene to stop it. Jake Holmes, who was in his brother's corner, says that much of the damage inflicted that night came because Holmes, realizing that the referee would be no help, was trying to knock Ali out in sort of a humane gesture that somehow seemed preferable to 15 rounds of protracted torture.

Pacheco says that when he asked Dundee to join his exodus two years earlier, the trainer replied that one good reason for staying on was that he would be a position to rescue Ali should a fight need to be stopped.

“No, you won't,” Pacheco told him — and it turns out he may have been right. In the Maysles film, both retired Newark scribe Jerry Izenberg and Kilroy confirm that Dundee's intervention came only after Herbert Muhammad had issued the order from his ringside seat.

* * *

There may be yet one more reason it took “Muhammad and Larry” thirty years to find an audience. Making a film about a fight billed as “The Last Hurrah” probably sounded like a better idea when it actually looked as if it would be, but once the Holmes fight was no longer Ali's last it may have lost some of its shine as an historical marker.

It wasn't in the rough cut distributed to the media beforehand, but in the final version screened at the Chelsea Theatre Monday, a postscript on the screen notes that in December of 1981 Ali fought for the last time in what the film gratuitously — and inaccurately — describes as an “unsanctioned” fight.

It seemed a curious, albeit deliberate, choice of words, designed to conjure up the image of some backwater bare-knuckle bout, or perhaps a winner-take-all fight to the finish in the basement of a mafia social club. It struck me that the label was tacked on to foster the impression that the Holmes fight was Ali's last “real” one, and that ten rounds against Trevor Berbick shouldn't even count.

Now, there's no question that a lot of silly, undignified things happened on the card billed as “The Drama in Bahama,” ranging from the absence of an actual ring bell (a Bahamian cowbell assumed that role) to the failure of the organizers to provide enough gloves for the undercard participants, but almost without exception those were the responsibility of promoter James Cornelius — a rank amateur — and not of the Bahamian Commission which sanctioned the card.

And make no mistake about it, Berbick-Ali took place in the Bahamas specifically because it was sanctioned there. If it hadn't been, Cornelius would have no doubt another jurisdiction that would sanction it.

Since Brad Kaplan seemed to have done most of the hands-on work with the ESPN version, I asked him about it after the screening. He initially tried to claim the fight hadn't been sanctioned at all, then that what he really meant was that “It wasn't sanctioned by a US commission.”

I asked him if he would have described it as “unsanctioned” had it taken place in Germany. At that point Maysles' partner began to yammer about the absence of recognized officials in the Bahamas. “The referee… and the judges…”

Actually, I told him, I believed that the referee that night was an American, Zach Clayton. (I double-checked when I got home. The same Zach Clayton who had refereed the “Rumble in the Jungle” seven years earlier was indeed the referee for Ali's swan song.)

Two of the judges, Alonzo Butler and Clyde Gray, were Bahamian appointees. The third, Jay Edson of Florida, was an official of more than thirty years' experience in world title fights. (Gray returned precisely the same score — 99-94 — Edson did that night, and Butler may have done a better job than either of them, since his 97-94 scorecard included just one even round, while Edson and Gray were indecisive enough to score three rounds level.)

It will be interesting to see whether the Berbick fight is still described as “unsanctioned” when “Muhammad and Larry” opens for business next Tuesday night.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoA Night of Mismatches Turns Topsy-Turvy at Mandalay Bay; Resendiz Shocks Plant

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering the Under-Appreciated “Body Snatcher” Mike McCallum, a Consummate Pro

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books