Articles of 2005

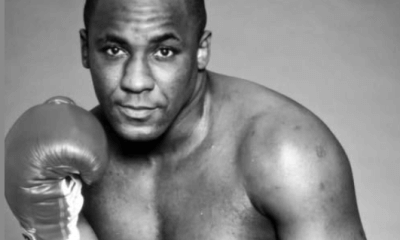

Kirino Garcia – Gutter to Great

By his own admission, Kirino Garcia was a petty thief, a street hustler, a panhandler, one of the thousands of cold-hearted lions that prowled the subterranean jungle of Ciudad Juarez, hungrily searching for strayed lambs. For him, a good day was one that ended absent the too familiar pangs of hunger or the pains of fresh wounds from an endless series of street fights. Home was a squatter’s cardboard shanty ruled violently by an alcoholic father, one that would beat him without reason or mercy.

Garcia was a seasoned warrior in a 22-year-old body etched with a roadmap of scars and grotesque tattoos when several of the border town coyotes convinced him that he could find the path to a better life in the boxing rings of the United States. For the coyotes, Mexico’s piranha of the poor, he had the potential of a human pit bull, but one they would coldly discard in the Chihuahua desert if his earning potential proved less than they demanded. Convinced that anything would be better than what he had, the hardened gang member turned his back on a future as empty as the pockets of his threadbare jeans and headed toward one of the few things he truly feared, the waters of the Rio Grande.

There are five routes between Ciudad Juarez and El Paso on the northern bank of the historic river, none of them requiring travelers to get their feet wet. There are the three main bridges connecting the city’s centers; a fourth span another seven miles to the west; and the fifth a few miles to the east. For Garcia, American law blocked all of them. Instead, shown the way by the coyotes, his first journey took him 100 miles west, through the desert that surrounds Ciudad Juarez to a narrowing of the waterway Mexicans call Rio Bravo, a crossing secluded by high sand dunes on both sides, which would become his favorite gateway into the United States.

“But I can’t swim,” he told his companions. “And I am afraid of the water.”

One of the coyotes pulled from his backpack a folded inner tube and an oversized air pump. “Blow this up,” he ordered Gomez. “You don’t have to swim; you can float across. Or are you a coward?”

Reading Garcia’s eyes, he stepped back quickly. “Never mind, I will blow it up for you,” he said. “With the tube, it will be easy, and we will watch you until you are safely across.”

After the crossing, there was another four-hour walk across the steamy Arizona desert, to a point where another group of coyotes picked him up and drove him into Tucson, where he was paid $85 to let a junior middleweight from New Jersey named Bobby Gunn hammer him for three rounds before the referee gave him the rest of the night off. “The best thing about that,” Garcia told Mike Katz, then the New York Daily News boxing writer, and me in Juarez a few years later, “was that a half-hour after the fight, I was in a diner getting something solid to eat. It was the first food I’d had in two and a half days.” Then he laughed. “The second good thing was when I returned home, I did not have to swim the river; I walked across the bridge.”

Between April 27, 1990 and January 29, 1994, Garcia fought 18 times, all but two of them after slipping across the river into Arizona or Texas. When he could, after the long trip in, he would curl up and catch a few hours of sleep in an alley. He fought when he was exhausted, and he was always exhausted. He fought when he was hungry, and he was forever hungry. Before he could eat, he had to fight. The only thing that added fat on his trips were the records of the men he fought.

“Sometimes he was so tired and so weak from hunger,” said Olvaldo Kuchle, the young Juarez boxing promoter who took over Garcia’s career after his 18th straight defeat, “he was not able to last past the first couple of minutes. He did not fall from a punch, but from hunger and exhaustion. The coyotes got their hooks into him and they did not see Kirino, they only saw the money. The coyotes are Mexican or Mexican-Americans from both sides of the river who turn these kids from Mexico’s slums into punching bags for anyone willing to pay them a few dollars. There’s no training. Nobody looks after them. Until he came with me, Kirino had never seen the inside of a gym.”

On the evening of October 10, 1990, Kuchle watched Garcia fight for the first time. It was not supposed to happen that way; Garcia and some friends had gone to the arena in Juarez to see Raul Gonzalez, a pretty fair middleweight out of Pasadena, California, with a 9-1-2 record. “I fought him four months ago,” Kirino told his friends. “He stopped me in four rounds.” That was no surprise; the Californian had stopped six of his last eight opponents. At the last minute, the Juarez promoter discovered Gonzalez’s opponent was a no-show. Desperate, the unhappy promoter jumped into the ring and asked if there was anyone in the audience willing to fight Gonzalez.

“I will,” shouted the irrepressible Garcia. “How much will you give me?”

After a purse was negotiated, the ring announcer introduced Kirino as Jesus Garcia-Lopez. Upon hearing that name, Kirino merely shrugged. This time, according to the record, Gonzalez knocked Garcia out in the second round, dropping his record to 0-4. “I promised the promoter I would fight,” Garcia told his amused friends later. “I never said how long.” Since that fight, everyone with the exception of Kirino’s immediate family has called him Jesus.

“Hey, that’s a pretty good name,” said Kirino. “Some pretty famous people have been named Jesus.”

By mid-1994, with his record standing at a dismal 0-18 and no one offering him fights, Garcia decided he had better find a different approach. He even considered training, an abysmal thought immediately discarded. While he was fighting as a professional, he still considered himself a street fighter, and street fighters treat gyms and trainers with disdain.

“All his life he ran with gangs,” said Kuchle. “He thought like a gang member. “Then there was the trouble with his father; he never went home. He was always on the street, asking people for money. He’d steal a little here, a little there. He didn’t have time to both train and steal, so he stole. He stole to survive. He didn’t have any equipment; he did not have anything but his fists. He loved to fight. When the gang from his territory would have a fight with a gang from another territory, he was the king of fighting. He’d say: ‘Hey, I am good at fighting. Why should I go to a gym?’”

But by early 1994, after his 15th loss, a six-round decision to a novice named Brian Shaw in Biloxi, Mississippi, the coyotes graduated him to 10-rounders. He fought two; he weighed 154 and 158 pounds, he was listed as 169 and 161, and both opponents were over 170. He took them both 10 rounds but lost the decisions.

“Hey, I was a Mexican named Jesus fighting gringos with names like Shaw and Parker and Carter in Mississippi. I would not have been surprised if the judges showed up wearing sheets,” said Garcia, grinning. “I’d like to fight all those guys in a back alley in Juarez.”

After the three losses in Mississippi, Garcia went to see Kuchle, who by now was the biggest promoter in Juarez. He begged for a local fight. “I’ll fight anybody; I don’t care who comes out of the other corner,” he said. “Please, I don’t want much, just a few dollars.” At first, Kuchle said no. “I have no time for fighters that do not train,” the promoter told him. “Look at your record, Jesus; it is very bad.”

When Garcia persisted, Kuchle said that if he trained a little, he would put him on his next promotion. Garcia trained, a little. On Sept. 9, 1994, he stopped a decent fighter named Norberto Bueno in six rounds. After four years of fighting as a professional, he decided that it felt good to win one.

“You see what training can do?” said Kuchle. “Now train some more, a little harder, please, and let us see how good you really can be.”

By then, Garcia was 26 and had a wife, Margarita and two sons, Kirino Jr. and Jose Carlos, and he knew Kuchle was his last chance to make a better life for his family. With money he had saved from his fights in the United States, he had purchased a small piece of land, a thin oblong slice of arid Mexican dirt, in the neighborhood where he always lived. Next he fashioned a two-room shanty framed with wood and covered by cardboard. The flimsy dwelling was scant protection against wind and rain.

“Some day I will build you a real home,” Kirino promised Margarita. Neither of them had ever known anything else.

Kuchle followed Kirino’s progress through daily reports from Felipe Delatore, whom he had assigned to train his latest tiger. The reports were always the same: Garcia had trained hard that day. “Half the time I had to kick him out of the gym,” said Delatore, laughing. “I had heard about Jesus, how he never trained. When I got him, I thought I’d have to fight to get him in the gym. Instead, I had to fight to get him out.”

As a test of Garcia’s newly discovered resolve, and of his progress, over the next seven months Kuchle sent him to Mexico City for three fights. No one in that group made it past the sixth round. “I guess you are now the best fighter with a 4-18 record in all of Mexico,” Kuchle told him jokingly. “OK, now we will make you some real money.”

Kuchle knew what he had. Garcia’s skills were limited, “but,” said the promoter, “I told him he had a hard head and nobody could hurt him, and he had a big punch. And he was a fighter, a real fighter, not some guy giving dance lessons. I knew the fans would love him.”

Fighting as a middleweight, Garcia won his next five fights, which earned him a shot at the Mexican 160-pound championship. After 12 grueling rounds against Eduardo Gutierrez, the judges ruled it was a draw. Driving himself even harder in the gym, Garcia dropped 154 pounds, his natural fighting weight. In December of 1997, he stopped former WBC welterweight champion Jorge Vaca to win the Mexican super-welterweight championship. That July, he defeated Terrence Alli to win the WBC’s international version of the title. By now, his fists were earning $10,000 to $12,000 a fight.

After the Alli victory, Kuchle called him into his office. “Jesus—,” he began.

“Why do you keep calling me Jesus? Garcia asked, grinning.

“Because that is your name,” said the bemused promoter.

Garcia’s grin widened. “No, my name is Kirino. Everybody calls me Jesus and I don’t know why.”

Actually, his proper name is Quirino Garcia-Vargas. But after Garcia spelled it out, and the proper authorities were notified, Kuchle changed the Qu to a single K because, he said, the initial K more suited a knockout fighter.

“OK,” said Garcia. “As long as people stop calling me Jesus.”

After that was settled, Kuchle told Kirino that it was time to move his family to a better home in a nicer neighborhood. “No way,” said Garcia, upset by the suggestion. It was his neighborhood. His friends lived there. He was comfortable there. Instead, he did what many of Mexico’s legions of poor do if they come into money. Replacing the cardboard with concrete, he converted the shanty into a comfortable six-room, tiled two-story home, one that he built with his hands and paid for with his fists.

By the time Mike Katz and I first met Kirinio in Juarez, and then a few days later in El Paso where he fought Roland Rangel in August of 1999, his record was 18-19-1 (remember he started 0-17), he had just made $50,000 for successfully defending his WBC International title against Eric Holland and was a rising IBA and WBA contender.

As I said, Katz was there covering the fights for The News; I was brought into El Paso (and out of retirement) by Dan Goossen to write biographical sketches of the fighters and to help with the launch of the new promotional firm, AmericaPresents.

I had known Katz since the night I tried to give him a Viking funeral, complete with a well-lit newspaper pyre, in a Las Vegas Hilton cocktail lounge in, I believe, 1979. By good chance I had started with the feet; by better chance, the flames were quickly extinguished by a flood of beer by others. OK, so we had a drink or two. Except for a period of two weeks after that when, for some reason, he kept throwing lighted matches at me, we have been close friends. For our trip across the Rio Grande to see Kirino, we hired a freelance photographer, whose name I cannot find in my old notes, who, along with taking pictures, was amenable to acting as our driver and interpreter.

I have never been comfortable with interpreters, whom I have always suspected of giving shorthand answers to my profound questions, especially when they use, say, a dozen or less words to tell you what the subject just said in a minute or two of nonstop answer. My worst experience happened in Los Angeles, when in 1977, I asked Carlos Zarate, through an interpreter, if he would feel uncomfortable fighting his best friend, Alfonso Zamora.

I listened while my interpreter, who had been provided by a local character known as Vein Head, faithfully framed, or so I thought, my question to the WBC bantamweight champion. I took note when Zarate gave me an odd look while he answered in Spanish. “Si,” said the interpreter, as he turned back to me and said: “Carlos said his mother wanted to be here but she is very sick.”

“Muchas gracias y adiós, amigo.”

The Garcia family home was in an area called Guadalajara Alta, a shantytown colonia of 1,000 dwellings, most of them made of wood and cardboard, where the acerbic brume of factory smoke and car exhaust turns the unwholesome air gray-brown. Kirino had promised his small wife, Margarita, things would be better, and one of the ways was air-conditioning, a luxury found in only four other homes in Guadalajara Alta.

“Thank God,” said Katz when we first stepped into the small living room and felt the artificial coolness. In all places possible were the trophies and mementoes of Kirino’s trips and accomplishments.

Kirino proudly introduced his family, first Margarita; then his parents (he long ago had made his peace with his father), Quirino Sr. and Maria; then his 101-year-old paternal grandfather, Jose Garcia, whom, Kuchle had told us, he adored; and finally his two sons and his daughter, the youngest of the Garcia clan, the diminutive image of her mother.

The grandfather, weathered and shrunken by the years but with a mind undiminished by time, studied the bohemianic Katz with watery but amused eyes. He said something in Spanish, bringing laughter from the others.

“What did he say?” I asked our interpreter, who was trying not to smile. When he hesitated, I repeated the question.

“Well, he said the hairy one looks like an unmade bed,” said the interpreter, with some embarrassment.

“Tell him lots of people say that,” I said, relieved that we had found an interpreter that did not try and skirt any verbal potholes.

After we said our goodbyes several hours later, our photographer drove us to a place called Black Bridge, a place Kirino had mentioned casually during our interview. We were just 40 feet off the main highway on the Juarez side, hard by an old railroad trestle that promised no passage north. To the left was a small peninsula jutting out from the far bank, but the stern presence of a no-nonsense fence in the middle declared that the southern most part belonged to Mexico. On the Mexican side of the grassy knob several youths were practicing soccer. A border patrol car was parked at the head of the tiny thumb of land, a chrome-and-steel message to the youths to keep the ball in their own court. Directly across the way, steep concrete embankments rose out the river, with the whole affair topped by a 30-foot to 40-foot steel fence. Light towers gave the place the grim look of 1940s Europe.

“This is where Kirino said he sometimes had to cross when he was in a hurry to get to a fight,” said the photographer, pointing grimly to where several bouquets of now-dead flowers lay on the ground by the near bank. “You can see why his wife said she was more afraid of him crossing the river than she was of his fighting. At least one or twice a month they will find a body in the water. Sometimes more.”

“The promised land,” Katz said, softly.

Two nights later, after being driven into central El Paso across the Stanton St. Bridge, from where he could have viewed the Black Bridge as the car passed over the historic waterway, a well-fed, well-trained, and well-rested Garcia won a majority decision over Rangle.

“I wish Kirino had started his career without losing those 17 fights,” Kuchle said, shaking his head. “That one big purse, the $50,000 he made fighting Holland, was because it was on Telemundo TV. It was the first television shot we could get him because he has such a horrible record. They see that record and they run away. They don’t know Kirino’s story. It is very frustrating.”

Since fighting Rangle, Kirino has added 19 victories to his chart, a dozen of them under the proscribed length, and he has fought on the mossy side of John Wayne’s Rio Bravo in places such as Miami, Laredo, Tucson and, twice more, El Paso without once ever having to float another inner tube. A few of his victims were less than challenging, the South of the Border variety, but the 5’10” reformed street thug scored 12-round victories over the likes of Simon Brown and Meldrick Taylor, and gave everything onetime-sensation Reid could handle before losing a tight decision. At the time, the former WBA super welterweight champion Reid was 17-1.

If you count the World Boxing Federation and the International Boxing Association, a couple of minor league members of the alphabet boxing cartels, he has twice fought for a world title. He lost by decision to then undefeated WBF 154-pound champion Steve Roberts at the Elephant & Castle Centre in London; and was a loser by decision to David Alfonso Lopez in their fight for the vacant IBF 160-pound championship.

“Both times he made a very decent payday,” said Kuchle with just a touch of pride. “By Mexican standards, he is a well-off young man. If the television people had not been so afraid of his misleading record, he would be well-off by anyone’s standard.”

Kirino is 36 now, understandably a shade battle weary, and his body has begun to complain about all those wars fought on an empty belly and no sleep, and suggests as only a body that has been the target of a thousand fists over the past three decades can suggest, that perhaps now is time to negotiate a truce with life.

Along with the 19 victories he has added since Rangle, there have been seven defeats and two draws. His last defeat, the one that spun his numbers to the current 37-26-3, came this past May in the Poliforo Juan Gabriel, a Juarez boxing citadel next to some soccer fields, was the most ignoble of all. In a fight that did not start until 2:06 Sunday morning, with the notes of Kirino’s entrance music El Rey still stirring the blood of his legions of local fans, the tattooed tiger from Guadalupe Alto was dropped by Gustavo Enriquez three times in the second round, the last by a paralyzing left hook to the liver. With 30 seconds left in the round, referee Juan Lazcano wisely signaled a ceasefire.

“I have an option for a rematch, but I will not exercise it,” said Kuchle, who signed a fighter and found a friend. “I will encourage Kirino to retire. I will tell him it is time.”

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoA Night of Mismatches Turns Topsy-Turvy at Mandalay Bay; Resendiz Shocks Plant

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering the Under-Appreciated “Body Snatcher” Mike McCallum, a Consummate Pro

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books