Articles of 2007

Andrew Maynard: I Didn't Get To Hurt People

After winning a gold medal at the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, Korea, light heavyweight Andrew Maynard was considered a shoo-in to become a professional champion. Several promoters passed on the opportunity to sign the two other gold medalists from the United States, Kennedy McKinney and Ray Mercer, in favor of targeting Maynard.

Although the then 24-year-old Maynard, who hailed from Laurel, Maryland, had only started boxing less than three years earlier, he was considered a better pro prospect than Olympic silver medalists Roy Jones Jr., who was robbed of the gold, and super heavyweight Riddick Bowe, who was considered a malingerer.

Maynard wound up signing with Maryland attorney Mike Trainer, who had guided Sugar Ray Leonard to mainstream superstardom and tens of millions of dollars in purses. Leonard became the integral figure in Maynard’s professional development.

Although Maynard began his career with 12 straight wins, 10 by knockout, he now says that signing on with Trainer and Leonard was the biggest mistake of his life.

“They took away my style, made me into a defensive fighter,” said the now 43-year-old Maynard who runs the boxing program at the Harlingen Foundation for Valley Sports in Texas.

“Instead of being a killer, they turned me into a pussycat. They wanted to make me fight like Ray, which was not my natural style. The new style stunk to high heaven. I didn’t get to hurt people. I spent more time running around the ring than standing and fighting.”

As an amateur, Maynard was an offensive whirlwind. Future professional light heavyweight title challenger John “Iceman” Scully was on the same elite international amateur team as Maynard in the years leading up to the Olympics.

At the Ohio State Fair national tournament in 1987, Scully beat the heavily favored Melvin Foster. Although relatively green, Scully amped himself up before and during the fight by repeating to himself that he had to fight like Maynard.

“Andrew was like a flyweight trapped in a light heavyweight’s body,” said Scully, who is now a respected trainer and author of a forthcoming book called “The Iceman Diaries.”

“I never saw a fighter throw so many punches. He was relentless. Nobody could hold him off. I won the title by imitating his style and just letting my hands go. He overwhelmed everyone he fought.”

Scully remembers seeing Maynard in one of his first televised pro fights, against durable journeyman Mike DeVito who was the first opponent to take Maynard the distance.

“I couldn’t believe it,” said Scully. “He was boxing in circles. I said ‘Wow, I’ve never seen him do that before.’ I remembered him always throwing at least 100 punches a round, even as an amateur.”

“It seemed like on day one of my pro career, I forgot everything I did that made me successful,” added Maynard. “Ray tried to make me a mirror image of himself, but that wasn’t me. He should have tried to bring out the best in me, not make me like him.”

Maynard’s first defeat, by seventh round TKO to Bobby Czyz, came in his 13th pro fight in June 1990.

“They had me running from him, rather than getting into a gunfight with him,” said Maynard. “My head wanted to fight him, but I was acting like a boxer and I couldn’t deflect his punches. I was doing everything Ray told me, and it was useless.”

Maynard says that Leonard also told him to not discuss business with his wife, which he now realizes was also a big mistake. He says that she was more loyal to him and had his best interests at heart more than anyone else he met during his pro career.

Maynard, who is the proud father of three children, said that keeping secrets from his wife caused him no shortage of grief.

“My goal as a fighter was to win a title and make $100 million, just like Ray did, for my family,” said Maynard. “When I was training and fighting, I was always thinking of my family and how my success would benefit them. Ray converted me to only think of myself, which was a big mistake. He hurt me so bad, in so many ways.”

After the loss to Czyz, Maynard put together six wins, including a third round stoppage of former champion Matthew Saad Muhammad, before being stopped himself by Frank Tate, a 1984 Olympian, in 11 rounds in New York in January 1992.

After that the losses came with much more frequency. Maynard was stopped by, among others, Anaclet Wamba, Egerton Marcus, Thomas Hearns, Sergei Kobozev, Torsten May, and Brian Nielsen before retiring in 2000 with a disappointing record of 26-13-1 (21 KOs).

“I lost my fire,” said Maynard. “I was going to be the best fighter in the world, throw 400 punches a round and land 398 of them. Instead, I lost my family, I lost millions of fans, and I never made any money.”

Although Maynard seems to have legitimate reasons to be angry, he still has an outward zest for life that is downright infectious. He refuses to wallow in his perceived victimization and still uses his verbal catch phrase, “Yeah, baby,” with the same enthusiasm he did more than 20 years ago.

Whether or not he is using it to camouflage a wounded heart is anyone’s guess.

“We are thrilled to have Andrew on our team,” said Alex Vidal, the executive director of the Harlingen Foundation for Valley Sports, who was responsible for recruiting Maynard into the program.

“His verbal trademark is ‘Yeah, baby,’ but he brings so much more to the program than his enthusiasm and love for the kids. Since he took over the program, enrollment has increased steadily and more kids are staying with the program.

“We attribute that to Andrew‘s participation,” he continued. “He has an engaging personality and is very approachable, he focuses on safety but is aggressive in training, and he has a great personal history. He won a gold medal, so that makes him a part of history. The community loves and respects him.”

Whatever success Maynard enjoyed at one time did not come without a high price being paid. He grew up a middle child, with three older sisters and a younger and older brother. His sisters, he said, use to beat him up on a regular basis.

“I was in the middle, so I was the odd man out,” said Maynard. “I couldn’t hang with the little brother or the big brother.”

His late father was an over-the-road truck driver who constantly told his children that nothing was more important in life than the love and support of one’s family. What the father didn’t realize was that his wife, the stepmother to his children, was molesting Maynard from the time he was a pre-pubescent.

“She would beat me in the afternoon, and then wake me up late a night to apologize,” said Maynard, who explained that her form of apologizing was to engage in sex.

This began when he was 11 years old and lasted until he ran away from home, consumed by shame and anger, when he was a 16.

Moreover, he adds, “She went through my brothers, but I didn’t know that when it was happening.”

Finally, looking for some direction and discipline in his life, Maynard joined the United States Army at the age of 21. When he told certain family members that he took up boxing in the military, they were not the least bit supportive.

“I had something to prove, no doubt,” said Maynard. “Some people told me I couldn’t take a punch. Other people said if I got hit, I would quit. I had to prove I would run from nobody. As an amateur I didn’t run from anybody. They ran from me. I was a great fighter until I met Sugar Ray Leonard and he turned me into a tap dancer.”

While training with an amateur team that included future pro champions Bowe, Michael Moorer and Al Cole, Maynard took an interest in Scully and Tim Igo, who, being the only white guys on the team, generally kept to themselves.

“I was like a four round fighter and these guys were the cream of the amateur crop,” said Scully. Even Tim (Igo) was an established amateur, who had fought Michael Bentt. Andrew was the life of the team, a real leader.

“He was always saying, ‘Yeah, baby,’ and juicing up the team. He was very energetic and positive, a great guy who I was in awe of. I didn’t have the confidence to approach any of them, especially Andrew.”

One day Scully was reading a magazine by himself. Maynard approached him and immediately made him feel like part of the team.

“He took me under his wing, and suddenly everyone was my friend,” said Scully. “When he stepped up, everyone followed. He turned out to be one of the most honest and humble people I ever met, and he treated me with a lot of respect.”

“My father always taught me that color meant nothing,” said Maynard. “But I knew that really wasn’t true. In elementary school I liked a white girl, but I knew I couldn’t say hello to her. When I saw Scully and Tim in their own white world, I knew what they were feeling.

“In the boxing game back then, whites hung with white and blacks hung with blacks,” he continued. “Whites would pull for whites and blacks would pull for blacks. Sometimes it was like a Joe Louis-Max Schmeling thing, but it was all bull. We were all on the same team and we were boxers. The only people that can really understand a boxer is another boxer, no matter what their color. Scully was cool. I liked him, and I never underestimated him.”

That is the kind of inherent decency that has made Maynard such a popular figure in Harlingen, which is in the Rio Grande Valley in South Texas.

Maynard’s abundance of experiences, both good and bad, is what makes him a great teacher and mentor. He doesn’t pull punches and he doesn’t underestimate anyone. Too many people underestimated him early on, and he proved them all wrong by winning a gold medal with nothing more than what amounted to on-the-job training.

“I lived it baby,” said Maynard. “The good, the bad and the ugly.”

Asked what would rock his world at this juncture in his life, he says that developing an Olympic athlete would be a wonderful culmination to a career that to date has brought him more downs than ups.

“That would be it,” said Maynard. “But I’d never try to force my style on someone else. I’d take their own style and try to perfect it. For so much of my amateur career, I didn’t know jack. I was beating everyone on the desire and determination to prove people wrong. As a pro, I listened to the wrong people.”

So his helping to navigate a talented young fighter through the snake pit of amateur would be a nice finale to a checkered career?

“Yeah, baby,” he responded with so much gusto I could “hear” and “see” his megawatt smile through the telephone.

The Harlingen Foundation for Valley Sports is a non-profit 501-C3 organization. Tax deductible donations can be mailed to:

Harlingen Foundation for Valley Sports

Airport Administration

3002 Heritage Way

Harlingen, Texas 78550

Phone: 956-466-2820

Articles of 2007

St-Pierre, Liddell, Clementi Win @ UFC 79

LAS VEGAS-A reinvented Georges St. Pierre proved he’s ready for the true Ultimate Fighting Championship welterweight title with a dominating win over Matt Hughes and Chuck Liddell returned to the win column in his big showdown on Saturday.

St. Pierre took the final chapter in the trilogy with Hughes and now is the UFC interim champion at the 170-pound division.

Hughes just shook his head after tapping out before a sold out audience at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. It was called “Nemesis” and St. Pierre conquered his nemesis.

“Georges is just a better fighter,” said Hughes (43-6) who beat St. Pierre several years ago, but lost two years ago in a title match. “I just don’t know how much longer I got.”

St. Pierre (15-2) found Hughes using a left-handed stance to change up his attack, but the Canadian quickly adapted and used his quickness, skills and raw strength to take Hughes to the ground.

“If it wasn’t for my wrestling training I wouldn’t have been able to adjust,” said St. Pierre who had been preparing to represent Canada’s Olympic wrestling team.

Inside the Octagon the Canadian was never in danger. In fact, Hughes was the fighter teetering for the entire fight that ended in 4:54 of the second round.

It wasn’t supposed to be that way.

Hughes, known for his wrestling skills, just couldn’t solve St. Pierre’s quickness. Every move the Illinois fighter attempted was squashed.

St. Pierre is now promised a fight against the current UFC welterweight champion Matt Serra, who pulled out of the fight with Hughes because of injury.

“If I don’t get my belt back, I’m going to consider myself champion,” said St. Pierre filled in for Serra with less than a month of training.

After dominating the first round on top of Hughes, the second round was even worse as St. Pierre landed elbows and fists. Though the Illinois fighter escaped from underneath, he was quickly thrown down. Within seconds St. Pierre grabbed Hughes left arm and turned it into an inescapable arm bar.

Hughes screamed out: “I tap!”

St. Pierre now awaits Serra to recover from his back injury.

The semi-main event was no less intense.

The light heavyweight showdown between Chuck “The Iceman” Liddell and Brazil’s Wanderlei “The Axe Murderer” Silva was a three-round punch out between two famous sluggers. In the end Liddell’s sharper punches in the first and third round decided the fight despite a knockdown in the second scored by Silva.

Silva (31-8-1) dominated the second round for four minutes and 30 seconds but Liddell rallied and took the Brazilian to the ground. Two judges were somehow impressed by Liddell’s last 30 seconds and inexplicably gave him that round.

With both fighters huffing and puffing, and Silva with a bad cut over his right eye, Liddell seemed the stronger puncher and landed a back-handed fist and a right hand that stunned the former Pride FC fighter Silva. But he survived the round.

The judges scored it 29-28, 30-27 twice for Liddell who won his first bout after back-to-back losses.

“I knew it was a big fight for everybody and especially for me to get back on track,” said Liddell (21-5). “He had a lot more than I thought he had.”

Silva, who was making his first UFC appearance, was gracious in defeat.

“He won,” said Silva. “I gave my best.”

Temecula’s Rameau Sokoudjou fell short against Brazil’s undefeated Lyoto Machida (12-0) in their light heavyweight contest. The Cameroon native was unable to use his punching power with effectiveness against the karate-trained fighter. Then, unexpectedly, Machida landed a left hand that dropped Sokoudjou (4-2) and proceeded to gain an arm triangle that forced a submission at 4:20 of the second round.

“I’ve been working on my ground game,” said Machida who wants a world title match. “I beat the Alaska assassin, the African assassin, what other assassins are left?”

A heavyweight bout featured two Southern Californians eager to punch out. But San Diego’s Eddie “Manic Hispanic” Sanchez’s experience proved decisive in beating Temecula’s Soa Palelei (8-2) with uppercuts for three rounds. With his nose bleeding profusely and sustaining three consecutive uppercuts, referee Mario Yamasaki stopped the fight at 3:24 of the third and final round for a technical knockout.

“He was out of gas,” said Sanchez (10-1). “He was always putting his head down.”

Undercard

A grudge fight between two Louisiana fighters ended in a decisive submission victory by Rich Clementi of Slidell over the favored Melvin Guillard of New Orleans. A rear naked choke at 4:40 seconds of the first round forced Guillard, who had been predicting domination, to tap out. Though the fight was definitively over, Guillard attempted to assault Clementi but referee Herb Dean grabbed the fighter.

“He still didn’t learn his lesson,” said Clementi after Guillard attempted to rush him after the fight. “I validated what he’s known for six years, I’m the better man.”

James “The Sandman” Irvin (13-5-1) was nearly put to sleep by an illegal knee to the eye from Brazil’s newcomer Luis Cane (8-1) in the first round of a light heavyweight fight. Unable to continue, Irvin was declared the winner by disqualification at 1:51. Cane seemed unaware that UFC rules disallow knees to the head while the person is on the ground. Some mixed martial arts organizations allow it.

Former Ultimate Fighter participant Manny Gamburyan (6-3) quickly took his fight to the ground with former boxer Nate Mohr (6-5). Once on the ground the lightweight used his quickness to grab an ankle and twist. Mohr screamed to stop the fight at 1:31 of the first round.

“I’m so sorry for you man,” said Gamburyan who suspects he broke Mohr’s leg. “Nate’s a great guy.”

San Diego’s Dean Lister (10-5) scraped out a unanimous decision win over Bulgaria’s punch-crazy Jordan Rachev (16-2) in a middleweight bout. The judges scored it 29-28 for Lister.

Articles of 2007

Pavlik Or 'Money': Fighter of the Year Is…

There’s nothing like the terror felt when you have a big black bear snarling and snorting and hunting you down, eager to stuff your tender head into his mouth, to make you run as fast as you’ve ever run.

Thanks, Dana White, aka the big black bear.

Thanks for waking up the semi-slumbering powers that be, and forcing them to acknowledge that boxing needed to step up its game, or be eaten alive, and shifted even further back in the sports world’s relevance race, in 2007.

With UFC threatening to snarf up those much lusted after PPV dollars, the suits went into overdrive, and worked smarter, and harder, to give fans compelling matchups.

They agreed to get along to get money, and they relegated the sanctioning bodies, with those moronic mandatories, and instead listened to you, the consumer, and booked the fights that made sense.

Nobody worked smarter or harder than the PR arms for HBO, and “Money” Mayweather, the artist formerly known as Pretty Boy Floyd. Through his appearance on the ABC reality dance competition “Dancing with the Stars,” and stubbornly effective marketing by HBO (24/7 before the De La Hoy and Hatton showdowns were masterful mini-movies which whet appetites of even non fight fans), “Money” emerged as a pay per view attraction who can take the baton as the premier earner from Oscar De La Hoya.

He transcended the sport, and boxing added another player to the mix of fighters that even non-fight fans in the US recognize the name of. Now there’s Mike Tyson, Oscar De La Hoya, and Floyd Mayweather…

Boxing, a sprawling mess of interests lacking a central organization that insures cohesiveness in marketing, and message, and mission, relies on a central figurehead to maintain its precarious perch in the mainstream sports information flow. Mayweather, a savvy marketer who has outgrown his periodic outbreaks of youthful indiscretions, is a superstar that fits our age to a T.

He knows exactly what buttons to push to keep his name in the papers-—or, more accurately today, on computer screens—and feeds us rabid presshounds of negativity and turmoil red meat, with his intra-familial beefs and 50 Cent-inspired rants proclaiming his peerlessness.

The only thing holding Mayweather back is his own talent, probably, as he owns too much of it. He blew out De La Hoya, and Hatton, and like Roy Jones in his heyday, he so dominates his opposition, that drama is missing from his fights. Most of us tune in to the sport to savor the drama that comes from one man reaching deep into the well of heart and guts to bring forth reserves even he didn’t know he possesses, and imposing his will on an opponent who had been imposing his will upon him. That sort of drama, as manufactured by the late Diego Corrales, is the variety that the sweet science can deliver like no other sport.

We saw it in excess in 2007, from my personal choice for 2007 Fighter of the Year, Ohio’s Kelly Pavlik.

He dug into his well, after getting knocked to the floor in the second round of his tussle with middleweight champion Jermain Taylor, and refused to lose.

All of us could apply his tenacity in staying on his feet, and roaring back to topple Taylor with a furious flurry in the seventh round of their Sept. 29 battle, in our own lives. We all could identify with, and root for, the TSS Fighter of the Year.

One could argue that Mayweather, with ultra high profile wins over De La Hoya and Hatton, who did as much as anyone to keep the sport relevant in the last 12 months, deserves the TSS FOTY honor. As referenced before, maybe his superior level of talent has set the bar too high for us nitpickers. We may be prone to be too hesitant to bestow praise on Floyd, because he makes it look too easy. Sorry, Money, it’s possible you are being penalized for just being too damned good. You certainly are the runaway frontrunner for Fighter of the Decade…

Pavlik, we didn’t know how good he was coming in to this year. We knew how good his promoter, Bob Arum, thought he was. But we reserved judgment, unwilling to make too much of wins over Lenord Pierre and Bronco McKart. We became believers, to a point, when the Ohio native showed boxing skill and a closer’s mentality with his January win over Jose Luis Zertuche (KO8), and true believers with his dominant march over Edison Miranda (TKO7), the heavily hyped Colombian who was no match for the Youngstown hitter’s work rate in their May match.

But we still withheld a measure of respect before Pavlik met Taylor, the middleweight king, in Atlantic City. Maybe we had been burned by (not as great as we were led to believe) white hopes in the past, and were worried that hype and marketing were his greatest attributes as a boxer. The respect came pouring forth when he stayed on his trembling legs in the second round of his September scrap with Taylor, and intensified when he closed the show with a KO crack in the seventh.

The fighter has to be rewarded for staying the course, and not allowing himself to be knocked off the title path since turning pro in 2000, and progressing at a sometimes snailish pace, and sticking with his no-name trainer Jack Loew even though some experts urged him to trade Loew in for a flashier model, and battling frail hands, and getting pinched for slugging an off-duty cop in 2005.

Pavlik’s rise in 2007 came the old fashioned way, via training his tail off, and staying on message mentally, and rising to the occasion when the situation offered a softer, easier choice.

There was no mega marketing machine bombarding our short attention spans with a campaign to make Kelly Pavlik into the torchbearer for the sport in 2007.

But the 2007 leg of his march to prominence reaffirms the best of what the sport has to offer, and reminds us that with talents like Pavlik, the sweet science will never crumble into obsolescence.

Articles of 2007

Resolution Time For Harold Sconiers

When Harold Sconiers of Tampa, Florida, looks in the mirror these days he doesn’t see the journeyman heavyweight with a 15-17-2 (10 KOs) record that most other people do.

What he sees is the dynamic, hard-hitting heavyweight who made it to the finals of the 1996 Olympic Trials, and began his pro career with six straight knockouts and one decision victory.

Since being stopped in the first round by then undefeated Bermane Stiverne, who had won all nine of his fights by knockout, in February 2007, Sconiers has completely reassessed his life and career.

He has come to understand what transformed him from an exciting amateur and fledgling young pro with seemingly limitless future to a nominal heavyweight who had at one point lost 10 fights in a row.

Now aligned with a new manager, David Selwyn of New York, he plans on utilizing that newfound knowledge to embark on what he believes will be the comeback story of 2008.

“I always knew I had a lot of talent, but I never let that talent completely develop,” said the 31-year-old Sconiers, who has lost to such notables as Clifford Etienne, Maurice Harris, Donovan “Razor” Ruddock, David Defiagbon, DaVarryl Williamson and Eric Kirkland.

“I had a lot of different problems, but my biggest problems were self doubt and self sabotage. I would do things to make sure I never rose above a certain level.”

During his intensive, exhaustive and brutally honest re-examination of himself, he chose to forego all of the negative aspects of his career and instead focus only on the positive. Through lots of reading and candid discussions with his former trainer Larry Berrien, he went about changing the mindset that made him so comfortable with losing.

The first thing he did was look at his complete record from a totally different perspective. Rather than just dwell on the losses, Sconiers lauded himself for beating six previously unbeaten or once beaten fighters. Among them was Ray Austin, who was 14-1 at the time and later challenged Wladimir Klitschko for the heavyweight title.

He also fought Edward Escobedo, who was 12-1, to a draw, and lost a split decision to Ruddock, who has always been a formidable ring presence.

When he examined his 10 fight losing streak, he realized that his opponents had a combined record of 164-32-8. Of the 32 losses, Harris, who had revitalized his once dismal career in much the same way Sconiers hopes to, had incurred 10 of them.

And the always competitive Sherman Williams, accounted for another 10, which means eight other opponents had only 12 losses between them. Several were undefeated at the time they faced Sconiers.

“Losing to all of those guys gave the boxing world the perception that I was washed up and just didn’t care anymore,” said Sconiers. “I realized I had to change that perception, and the only way to change it was to change my old habits and my old ways of thinking, dissect everything I’d been doing wrong, and working really hard to establish a new belief system.”

Tapping deep into his own psyche, Sconiers came to realize that much of his lack of self worth was rooted in childhood issues. As a kid he had a passive personality, and both of his parents were college graduates who held what he calls high ranking positions in the corporate world.

He was bright enough to skip grades in school and he scored high on IQ tests. In no way was he destined to become a boxer. His parents had told him on many occasions that he would be well-suited as psychiatrist or attorney.

His life changed when his father held a Mike Tyson fight party at the family home. To say that Sconiers was mesmerized would be a gross understatement.

“I was instantly locked in,” said Sconiers. “I told myself that I have to do this.”

Sconiers ventured to the Frontline Outreach Gym in Orlando, where he met Antonio Tarver, who was roaring through the amateur ranks en route to the 1996 Olympics. Because Tarver was a few years older than Sconiers, he became a surrogate big brother to him. To this day, Sconiers has the utmost respect for Tarver as both a fighter and a friend.

During Sconiers’ amateur career, which consisted of 77 fights, of which he lost 9, his mother continuously reminded him that, in her opinion, “boxing was for dummies.”

Still, he managed to win a silver medal in the 1996 U.S. Nationals, where he beat eventual Olympic representative and future heavyweight title challenger Calvin Brock, as well as the finals of the 1996 Olympic Trials. In that tournament he lost to Williamson and Lamon Brewster.

When his pro career began to get derailed, the young and immature Sconiers blamed everyone but himself for his shift in fortune.

“I thought the problem was outside me, and thought everyone was responsible but me,” he said. “I dumped Larry in order to self-manage myself. I left what had always kept me grounded. Some of the fights I lost I could or should have won. There’s no way I should have lost to Etienne, but all I did was show up. The Ruddock fight should have been mine.”

As Sconiers lost interest and motivation, he also began dabbling in drugs and alcohol. More times than not, he would take fights on short notice. Even if he had time to train, he never cared if his opponents were switched or where he was lacing them up. Resigned to the fact that he was just fighting for money, he didn’t train hard, if at all.

He’d also pick up a few dollars working as a sparring partner for the likes of Etienne, Shannon Briggs, Jameel McCline, Larry Donald and Kirk Johnson, but the passion was gone. Many of those fighters, as well as their trainers, told Sconiers to snap out of his trance because he was a lot better fighter than he gave himself credit for.

While working with Etienne, the esteemed trainer Don Turner told Sconiers he could make him heavyweight champion of the world if only he’d “get his (stuff) together.”

Sconiers said he was at his personal abyss in mid-2003, when he was stopped by Kirkland, who was 16-1, in the first round in Vallejo, California.

“That was a real bad time for me,” he said. “I was up all night using drugs and alcohol and just didn’t care about anything.”

Although it would be nearly four more years before Sconiers embarked on his personal renaissance, when he looks back on his sordid past that is his most vivid memory. He has learned to use that memory to his advantage.

“A lot of people go down the same route I did and destroy themselves completely,” he said. “I was close to that point around the time of the Kirkland fight, but managed to survive another four years. It is so obvious to me now that I was trying to destroy myself.”

Sconiers is the first to concede that once you fall into the role of an opponent, it is hard to extricate yourself.

“A lot of guys go through this and fall by the wayside,” he said. “Look at Emanuel Burton (Augustus). He’s an immensely talented guy who’s good enough to be competitive and probably beat anyone. But he is in that opponent role, which is hard to snap out of.”

Having done lots of reading on positive thinking and overcoming psychological roadblocks, as well as completely revising his physical training regimen, Sconiers believes he has snapped out of it.

Besides the steadfast support of his beloved wife of six years, Jennifer, who just earned her master’s degree, he believes that his association with Selwyn is a pivotal component to the success he foresees for himself.

They plan on having a momentous and memorable 2008.

“Harold says he is going to be the Cinderella Man of 2008,” said Selwyn. “We plan on keeping a very busy schedule. History has shown that heavyweights are always just a few wins away from redemption. At his best, Harold is very good. It is undeniable that he was his own worst enemy in the past. Now he believes in himself, Larry believes in him, and I believe in him. I’m really looking forward to working with him so he can reach his full potential.”

“We plan on a busy schedule and a lot of upsets,” added Sconiers. “After my first couple of wins, people will probably say they were a fluke. I’m not quite the Cinderella Man and I’m not quite Rocky, but I am an underdog who can make it. Hope sells in boxing, and I plan on being one of the biggest stories of the new year.”

Manager Dave Selwyn can be contacted at: Boxingkid@aol.com or 845-893-2829.

*photo courtesy Harold Sconiers

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoA Shocker in Tijuana: Bruno Surace KOs Jaime Munguia !!

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Ortiz-Bohachuk Thriller has been named the TSS 2024 Fight of The Year

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFor Whom the Bell Tolled: 2024 Boxing Obituaries PART ONE (Jan.-June)

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoLucas Bahdi Forged the TSS 2024 Knockout of the Year

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

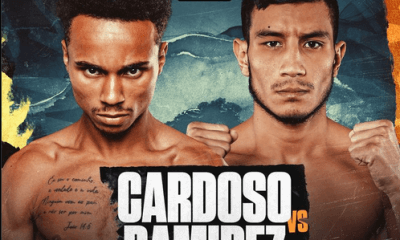

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCardoso, Nunez, and Akitsugi Bring Home the Bacon in Plant City

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoL.A.’s Rudy Hernandez is the 2024 TSS Trainer of the Year

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoUsyk Outpoints Fury and Itauma has the “Wow Factor” in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk is the TSS 2024 Fighter of the Year