Featured Articles

Bruce Lee in Boxing Trunks

“Most people aren’t aware of it, but Bruce Lee was very into boxing. Scientific boxing.”

—Dan Inosanto

Game of Death, Bruce Lee’s unfinished masterwork, gave us the enduring image of the first international Asian superstar in a yellow tracksuit, ascending levels of a pagoda where assorted challengers await him. On the third-floor was Filipino-American Dan Inosanto, a friend and student of Lee who took the role as a favor. The challenger that loomed on the fifth floor was billed as “The Unknown” and played by Los Angeles Laker Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Lee’s climactic match against the seven feet two inch giant has awed adolescent boys ever since, especially the short ones.

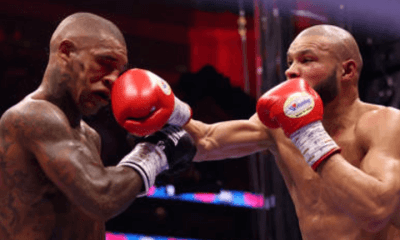

Fans of the dragon didn’t miss the tribute last Saturday night. Nonito Donaire made his way to the ring wearing a robe and trunks modeled after Lee’s iconic tracksuit. Dan Inosanto, now seventy-five years old, followed close behind while challenger Jeffrey Mathebula—the Abdul-Jabaar of Jr. Featherweights—loomed up ahead. Donaire admitted to HBO that he’d “never faced a guy who’s taller than me, especially not five inches taller than me. I want to figure out that kind of style.” He wants to figure out all kinds of styles, “step by step,” as if climbing a pagoda.

Donaire is a fighter after Lee’s own heart. Game of Death was, after all, intended to do more than empower sprouting boys to feel their oats. Lee intended it to showcase a theory of combat that revolves around formlessness, around the ability to adapt to changing conditions and different styles. “Things live by moving,” he said, “and get stronger as they go.” Every successive opponent that he conquered in the film symbolically led him to a higher level, a higher state of being. Few got it. He tried explaining himself on a Canadian talk show in 1971, particularly his desire to teach how to “express one’s self honestly, not lying to one’s self” but the host was as receptive as a bucket of ice. “This is very unwestern,” he said.

Nevertheless, Lee’s theory of progressive spirituality in the form of combat has been radically applied by another beast from the East: Manny Pacquiao has ascended through boxing’s pagoda to seize four true crowns in four weight divisions. Bruce Lee went straight to his head and landed in his hairstyle.

Donaire’s receding hairline doesn’t allow for that kind of tribute, and he has not—despite the boxing world’s penchant for lying to itself—taken a true crown yet. But he too is a disciple: “I want to learn every aspect of who I am and what I can do,” he says. He studied film before the Mathebula fight; he studied Game of Death. Like Lee against Abdul-Jabbar, he attacked his towering opponent from two ranges, outside Mathebula’s reach and pressed up against Mathebula’s chest. He angled around, dipped under long hooks, and threw looping shots up where the air is thin to catch that dangling chin.

I was half-expecting him to flick his lip with his thumb.

…..

Boxing was part of Lee’s beginning. He boxed in Hong Kong as a teenager and was good enough to win a tournament involving fifteen high schools in the late fifties. Inosanto is confident that he could have been a top-ranked lightweight in the sixties, during the era of Carlos Ortiz. His intensity, speed, and dynamism would have been assets, though what would have set him apart was the “unbelievable power” he could generate despite his size.

In 1959, Lee left Hong Kong and began teaching Wing Chun in the United States. He had not, at the time, evolved out of the traditional school of martial arts with its upright stance and straight-ahead attack and he had not yet incorporated the feints, angles, and broken rhythm he would become known for. It took a Golden Gloves boxer named Leo Fong to demonstrate the value of these decidedly Western ideas. He did it by inviting Lee to attack him. Lee rushed forward with chopping hands and Fong simply stepped off to one side and turned over a left hook. It was an epiphany for the young master. Fong would soon convince him that the typical martial artist’s stance, with the lead hand held high and the back hand held by the solar plexus, was inferior to the American boxer’s stance, where the lead hand is low and the back hand is high enough to protect the chin. “I like it because I can’t trap your lead hand,” Lee told Fong. “Over the next few years,” Fong recalled, “Bruce completely changed his primary fighting stance and eventually adopted more of a boxing stance as his own.” This happened around the time that Lee began developing his dynamic style.

Boxing —practical, spontaneous, and multidimensional— may have been the impetus that shifted Lee away from traditional forms and toward the fighting system that became Jeet Kune Do.

The Tao of Jeet Kune Do, which is a compilation of his notes, relies heavily on boxing principles. Lee referenced Jack Dempsey and Edwin L. Haislet’s Boxing (1940) at least twenty times. He reportedly owned more than a hundred boxing books in his library.

He also owned one of the largest collections of fight films in the country and would invite associates to his house for marathon viewings on Wednesdays. “Bruce used to analyze those films,” recalled one of them. “We could only take it for a couple of hours, but Bruce could sit there for eight or 10 hours and still show the same interest and enthusiasm he showed in the first five minutes.” He was capable of mimicking not just the Ali shuffle, but the Sharkey roll, Joe Louis’s six-inch punch, and Kid Gavilan’s bolo punch (which was, incidentally, another import from the East, as is the bolo itself. Filipino fighters based in California during the 1930s introduced it.) Whenever a move interested him, Lee, a southpaw, would rewind the film, stand and turn his back to watch it in a mirror, and practice it.

Joe Lewis, a karate champion, attended the “Wednesday Night Fights” hosted by Lee. “Willie Pep, reputed by many to be pound for pound the best boxer of all time,” he said, “was the fighter whose footwork Bruce and I would study.”

In round two of Saturday night’s bout, Donaire mimicked Lee’s dancing footwork. However, Lee’s dancing footwork wasn’t his own—it was Willie Pep’s. Boxing begins and ends the circle.

…..

The Sweet Science whispered its truths to the dragon and the dragon listened. Boxing’s impact on Western culture cannot be overestimated. Neither can Bruce Lee’s. Lee learned from Western culture and then confronted it. “In the United States,” he said, “something about the oriental, the true oriental, should be shown.” And so it was. Lee single-handedly redefined the image of the Asian male while the whole world watched and learned. The buck-toothed, bowing oddity portrayed on film since Charlie Chan was rolled back in the wake of his fame. It happened as fast as that kick he landed on Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s face. Asian boys suddenly had nothing to be “so sorry” about once he lifted their chins and gave them an image to be proud of; the image of himself, an image they could find in the mirror.

Nonito Donaire was one of them. A bullied child made to feel ashamed of his appearance has evolved into a true disciple of the dragon. He looks in the mirror and sees Bruce Lee in boxing trunks

—and Bruce Lee looks back.

____________________

References include “Talking with Leo Fong,” by WR on Real Fighting.com; Jerry Beasley’s “How Bruce Lee’s Jeet Kune Do Techniques Revolutionized Joe Lewis’ Karate”; EsNewsReporting’s “How Boxing Helped Bruce Lee Become a Legend”; and Bob Birchland’s essay “Bruce Lee Training Research: How Boxing Influenced His Jeet Kune Do Techniques.”

Springs Toledo can be reached at scalinatella@hotmail.com“>scalinatella@hotmail.com.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

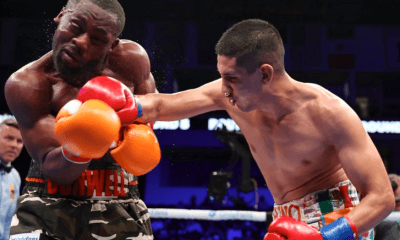

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFloyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

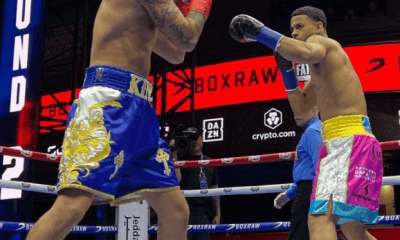

Featured Articles4 weeks agoChris Eubank Jr Outlasts Conor Benn at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoJorge Garcia is the TSS Fighter of the Month for April

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

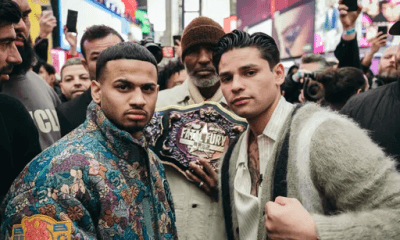

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRolly Romero Upsets Ryan Garcia in the Finale of a Times Square Tripleheader

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 324: Ryan Garcia Leads Three Days in May Battles

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCanelo Alvarez Upends Dancing Machine William Scull in Saudi Arabia

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoUndercard Results and Recaps from the Inoue-Cardenas Show in Las Vegas

3 Comments