Featured Articles

ESPN THE MAGAZINE’S “CUBA ISSUE” STIRS STRONG FEELINGS

The Feb. 17 issue of ESPN The Magazine, like so many that preceded it, was largely devoted to a particular theme. In this instance, the cover photo, of the Los Angeles Dodgers 23-year-old phenom, right fielder Yasiel Puig, hinted at much of what was inside: a series of articles about Cuba, which the publication proclaimed was the launching point for the “opening (of) the next great pipeline in sports.”

That pipeline has been free-flowing from Cuba to the United States and other countries for many years, predating the Fidel Castro-led revolution that toppled the admittedly corrupt regime of President Fulgencio Batista in 1959, although any use of the word “free” doesn’t come close to describing living conditions in the island nation located just 90 miles south of Key West, Fla. The Soviet Union might have formally dissolved on Dec. 26, 1991, which led to the tearing down of the concrete-and-barbed-wire Berlin Wall and the figurative but no less real “Iron Curtain,” but the “Sugar Cane Curtain” that continues to separate Communist Cuba from the U.S. remains in place. That reality is much to the chagrin of the large Cuban-American population in south Florida and more than a few government dissenters in Cuba’s population 11.3 million, who dream of making it to our shores, or at least of the restoration of the freedoms which are denied them in their homeland.

“Some Americans who have never experienced anything else don’t understand how important freedom is,” said Maria Alejandra Santamaria, a retired educator in Miami who came to America from her native Havana in 1968. “Freedom should never be taken for granted. You have to fight for what you want. You have to earn your happiness, and that only comes through hard work and dedication. It’s not easy; nothing worthwhile ever is. But when you have been through so much to even get to the United States, and to live free, you realize what a precious gift that is.

“There are so many young Cubans who live there now who are as desperate to leave as we were because they know there is something else, something better, than they have grown up under.”

Cubans know there is something better in no small part because of breakout athletes like Miami Marlins pitcher Jose Fernandez and Puig, Cuban defectors who finished first and second, respectively, in the voting for the 2013 National League Rookie of the Year Award, and, in their early 20s, already are millionaires. They know something of the repeated attempts by those players, often at the risk of their own lives or of imprisonment, to reach the U.S. They are familiar with the story of WBA and WBO super bantamweight champion Guillermo Rigondeaux, the two-time Olympic gold medalist (2000 and 2004) who tried on seven different occasions to escape Cuba before he finally reached the U.S. and freedom. In doing so, Rigondeaux – who was incarcerated after one failed defection attempt and was stripped of his national-hero status and his most prized possession, a car – made the gut-wrenching decision to leave behind his wife, 5-year-old son, 15-year-old stepson and seven siblings.

“You are a champion, and it means nothing,” Rigondeaux is quoted in the ESPN piece about him and other Cuban boxers who made it out. “We are like dogs. After all your time is over, you end up telling stories on a street corner about how you used to be a star.”

What is not so widely known are the success stories of Maria Alejandra Santamaria and her husband Jose (known to his many friends and family members as Pepe), who arrived in New York City with little more than the clothes on their backs and, over time, forged new, prosperous lives for themselves and their three children, all of whom were born in the U.S. Including brothers, offspring and in-laws, there are 18 members of the Santamaria clan who live in and around Miami.

“Many Americans believe that what has happened in other countries, including Cuba, can’t happen here,” said Roxana Santamaria, the youngest of Pepe and Maria’s grown children. “That is the danger.”

I know the Santamarias’ saga well, because Pepe is my wife’s first cousin. My beloved Anne is half-Cuban, her late mother, the former Georgina Ortiz, having met and married my future father-in-law, the late J.E. d’Aquin, in 1948 while he was in Havana as an employee of the U.S. government. Anne I met on a blind date as high schoolers in New Orleans in 1965 and we married 3½ years later. Although I am not Cuban – my lineage is a hodgepodge of Spanish, English, French, Irish and Swedish – our four children are part Cuban, as are our five grandchildren. Havana is a city that for many years I have felt connected to, although I have never been there and probably never will. Maybe that is because I have become so immersed in the Cuban culture through our trips to Miami, which sadly are less frequent than I would prefer. When Anne and I are visiting the Santamarias, Maria – better known by her nickname, “Marita” –makes sure I am always well-fortified with café con leche, a particular favorite, and mounds of black beans and plantains. While platters of food are not being passed around the dinner table, tales of what was and hopefully will be again are also exchanged.

“Castro was putting people in concentration camps,” Marita told me of those harrowing days for those who opposed the bearded one’s totalitarian rule. “I didn’t want Pepe to go into a concentration camp. I asked a relative, who used to live here in Miami, to send Pepe money for airfare so he could go to Madrid, Spain. The day before Castro’s people came to arrest him, he left for Madrid. He stayed there for a few months before, with the help of the Catholic Conference, he was able to join me in New York.

“It was terrible being separated. Many Cubans went to one country or another and they never were able to get back together with their families. It was hard for Pepe to make the decision to leave, but it was his only chance to stay out of the concentration camp, where I know that some people died.”

Anne returned with her parents for a brief visit to Havana when she was an infant, and again in 1955 or ’56 (she doesn’t recall the exact year), when she was 6 or 7. What she does recall is the sound of gunfire echoing in the hills when she and her parents went to see her mother’s aunt.

“It was machine guns, I think,” she said. “We knew that there was fighting between Castro’s supporters and Batista’s soldiers in the mountains. I remember being terrified. I think we stayed there for just a day or two before we went back to Havana.

“All my life I’ve wanted to go back there, but after Castro took over we never did, of course. I hope someday, if things are different, I’ll be able to visit again.”

As a sports writer for these past 43 years, and even before, Cuba and Cuban athletes have drifted in and out of my consciousness with surprising regularity. For reasons I still don’t quite understand, one of my favorite pitchers as a kid was Camilo Pascual, the Cuban righthander with the big overhand curveball who performed with distinction for the Washington Senators and Minnesota Twins. I also liked the flair with which outfielder Minnie Minoso played both in the field and at the plate, a style which is replicated by the swashbuckling Puig. Then again, a bit of showmanship has always been an integral part of the Cuban approach to sports. What Minoso brought to the diamond the great welterweight champion Kid Gavilan, with his signature “bolo punch,” brought to the boxing ring.

Said Jose Fernandez, the Marlins pitcher, in ESPN The Magazine: “I am who I am. I come from a different place. Baseball in Cuba’s a lot more emotion, a lot more passion. At the end of the day, it’s a game, and you’re supposed to have fun, right?”

I’m not sure if it was fun I was seeking when I requested the assignment from my editors at the Philadelphia Daily News to cover the 11th Pan American Games in Havana, which if nothing else would have given me an opportunity to report back to Anne all that I had seen of the land of her mother’s birth. But much to my regret, a columnist with more pull and seniority, Bill Conlin, got that gig.

I did, however, cover the 10th Pan Am Games in Indianapolis, Ind., in 1987, which produced no shortage of sights and sounds that made clear the wide gap, ideological and otherwise, that existed between Castro’s Cuba and the U.S.

One of the stories I wrote was about the conundrum in which members of PAX-I, Indianapolis’ Pan Am organizing committee, found themselves while trying to smooth the ruffled feathers of the Cuban delegation after an anti-Castro group paid for a private plane to fly over the Pan Am site towing a banner urging Cuban athletes to defect.

Also on the political front, officials of the American Legion, who had agreed to allow the use of their outdoor mall for the closing ceremony, withdrew that consent when it was learned that a central theme would be the honoring of Cuba, which was to be the site of the 1991 Pan Am Games. The venue for the closing ceremony was shifted to the Hoosier Dome, but even that move wasn’t without incident. PAX-I had hired Gloria Estefan and the Miami Sound Machine, a popular salsa-rock group, to provide entertainment sure to please the glut of Spanish-speaking visitors. But the Cuban delegation reacted to the Miami Sound Machine with the same lack of enthusiasm they might have shown Sylvester Stallone had he paraded through the athletes’ village dressed as Rambo. Cuban Olympic Committee president Manuel Gonzalez Guerra noted that Estefan’s father once was a bodyguard for Batista’s wife. Guerra said the selection of Estefan was a “provocation” of the Cuban delegation and he threatened to boycott the closing ceremony.

The Cubans did, in fact, attend the party, but when Estefan and Miami Sound Machine took the stage, Guerra and his athletes stood up, turned their backs and remained still and silent throughout the show. I have sometimes wondered how many of the protesting Cuban athletes later defected, or tried to.

There was intrigue in competition, too, not the least of which was in boxing. Although the U.S. led the way with 370 total medals and 169 golds, Cuba finished second in both categories, with 175 total medals and 75 golds. Ten of those golds and a bronze went to Cuban boxers, while American fighters were limited to one gold, four silvers and four bronzes.

“Everybody is dwelling on the Cuban thing,” one of the U.S. boxers, future WBA super middleweight champion Frankie Liles, said of the bitter rivalry that was developing in the ring between the two countries. “One of the things that’s in the back (of the American boxers’ minds) is stopping the Cubans – not just beating the Cubans, but stopping them.”

Liles and his teammates came up way short, and four years later, at the Pan Am Games in Havana, the Cubans were still kicking American butt inside the ropes: 11 golds (no silvers or bronzes) to one gold, four silvers and four bronzes for U.S. fighters. It’s little wonder American promoters were so hot to get their hands on some of the more accomplished Cubans.

Then again, not every Cuban superstar, in boxing or baseball, viewed defection as a path to paradise. In 1974, Bob Arum and Don King each tried to entice celebrated heavyweight Teofilo Stevenson, then 22 and the winner of the first of his three Olympic gold medals, to come to America to fight an aging Muhammad Ali. But Stevenson, who was 60 and pretty much broke when he died last year, refused to be swayed. “What is a million dollars,” he reasoned, “compared to the love of eight million Cubans?”

The baseball equivalent of Stevenson, according to Conlin, was Omar Linares, whom Conlin observed at the ’91 Pan Am Games in Havana. “The best third baseman I have seen not named Mike Schmidt,” wrote Big Bill, who also noted that Linares was a “devout Fidelista” who wasn’t going to defect for anything so crass as stacks of U.S. dollars.

All I know is that the Havana I have heard about so often, the one of the Santamarias’ pre-Castro memories, remains an alluring destination for those of us who have ever read a Ernest Hemingway novel. You don’t have to fire up a contraband Cohiba to know something has been lost to Americans who are prohibited from traveling to Cuba, or to realize that even more has been lost to Cubans who haven’t been able to make it to this land of the free.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

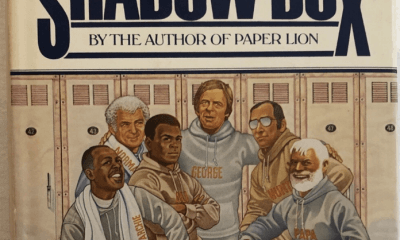

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates