Featured Articles

Behind the Scenes At Pacquiao-Bradley 2: Part One

Shortly after one o’clock on the afternoon of Thursday, April 10, Manny Pacquiao concluded a series of satellite interviews that originated in Section 118 of the MGM Grand Garden Arena. The interviews were designed to promote his April 12 fight against Tim Bradley and everything had gone according to plan.

“My advantage is that I’m quicker than him and punch harder than him,” Pacquiao told one interviewer.

When asked about being knocked out by Juan Manuel Marquez, Manny responded, “Sometimes these things happen. That is boxing.”

An interviewer for Sky-TV posed the all-but-obligatory question of whether or not Pacquiao would fight Floyd Mayweather.

“I’m happy for that fight,” Manny said. “If not in boxing, maybe we can play one-on-one in basketball.”

As for his musical talents, Pacquiao acknowledged, “I can sing, but my voice is really not that good. The fans like my singing because of what I’ve done in boxing.”

At one point, Manny noted, “Sportsmanship is very important to me because it is my way of displaying respect to the sport of boxing, to my opponent, and to the fans.”

After the interviews ended, Pacquiao was leaving Section 118 when a voice from across the arena shouted out loud and clear: “Manny, we love you. Manny, we love you. Manny! Manny!”

Pacquiao turned to acknowledge the fan, one of many who follow him wherever he goes. Then his face broke into a broad smile. The man shouting was Tim Bradley.

Manny waved, Tim waved back. In two days, they would try to beat each other senseless in a boxing ring. But for now there was fondness between them.

Welcome to Pacquiao-Bradley 2, featuring two elite fighters who carried themselves with dignity and grace throughout the promotion with no lapse of decorum by either man.

Pacquiao’s saga is well known. In an era of phony championship belts and unremitting hype, he has been a legitimate champion and also a true peoples’ champion. The eleven-month period between December 6, 2008, and November 14, 2009, when he demolished Oscar De La Hoya, Ricky Hatton, and Miguel Cotto were his peak years in terms of ring performance and adulation.

That was a while ago.

Tim Bradley believes in himself and epitomizes Cus D’Amato’s maxim: “When two fighters meet in the ring, the fighter with the greater will prevails every time unless the opponent’s skills are so superior that the opponent’s will is never tested.”

Most elite athletes are overachievers. Bradley comes as close to getting one hundred percent out of his potential as anyone in boxing. He’s a more sophisticated fighter than many people give him credit for. He’s not just about coming forward, applying pressure, and throwing punches. He has a good boxing brain and knows how to use it. But he isn’t particularly fast, nor does he hit particularly hard. The keys to his success are his physical strength and iron will.

“I’m not the most talented fighter in the division,” Tim acknowledges. “Not at all. There are guys with better skills and better physical gifts than I have. Where I separate myself from other fighters is my determination. I wear the other guy down. That’s what it is; hard work and determination. I work my butt off. I come ready every time. People keep saying that I don’t hit that hard, that I don’t box that well. But I keep winning, don’t I?”

Before each fight, Bradley promises himself that his opponent will remember him for the rest of his life. Marvin Hagler is his favorite fighter. Blue-collar work ethic, shaved head, overshadowed by boxing’s glamour boys.

Pacquiao and Bradley met in the ring for the first time on June 9, 2012. During that bout, Tim suffered strained ligaments in his left foot and a badly swollen right ankle. He was rolled into the post-fight press conference in a wheelchair.

“Both of my feel were hurt in that fight,” he recalls. “And I had a lion in front of me. All I could do was take it round by round. And it wasn’t enough to survive each round. I had to win them.”

Bradley, as the world knows, prevailed on a split-decision. A firestorm of protest followed.

In the aftermath of the bout, Pacquiao was an exemplary sportsman. “I’m a fighter,” Manny said. “My job is to fight in the ring. I don’t judge the fights. This is sport. You’re on the winner’s side sometimes. Sometimes you’re on the loser’s side. If you don’t want to lose, don’t fight.”

But others were less gracious. The beating Bradley took outside the ring was worse than the punishment he took in it.

“After the fight,” Tim remembers, “they announced that I was the winner. I was on top of the world, and then the world caved in on me. It should have been the happiest time of my life, and I wound up in the darkest place I’ve ever been in. I thought the fight was close. I thought the decision could have gone either way. You prepare your entire life to get to a certain point; you get there; and then it all gets taken away. I was attacked in the media. People were stopping me on the street, saying things like, ‘You didn’t win that fight; you should give the belt back; you should be ashamed of yourself; you’re not a real champion.’ I got death threats. I turned off my phone. All I did was do my job the best way I could, and It was like I stole something from the world.”

“It was bad,” says Joel Diaz, who has trained Bradley for the fighter’s entire career. “Tim was all right with people criticizing the decision, but the personal attacks really hurt. Tim is a proud man, and it was hard for him to walk tall anywhere.”

In Pacquiao’s next fight, he suffered a one-punch knockout loss at the hands of Juan Manuel Marquez. Eleven months later, he rebounded to decision Brandon Rios. Meanwhile, Bradley edged Ruslan Provodnikov in a thriller and outboxed Marquez en route to another split-decision triumph.

That set the stage for an April 12 rematch at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. Bradley was the reigning champion, but Pacquiao was the engine driving the economics of the fight. The event was labeled “Pacquiao-Bradley 2”, and Manny was guaranteed a $20 million purse ($6 million less than for their initial encounter). Tim was promised $6 million (one million more than the first time around).

Each fighter felt that there was unfinished business between them.

“There is a big question mark on our first fight,” Pacquiao said at a February 6 press conference in New York. “This time, we will answer that question.”

“The whole Pacquiao situation still bothers me,” Bradley added. “So on April 12, I’m going to clean that up.”

Fight week had a strange feel to it. The Pacquiao-Bradley rematch hadn’t taken place earlier because neither HBO nor Top Rank (which promoted both fighters) thought it would sell well. But after Marquez starched Pacquiao and Bradley beat Marquez, the possibility of beating Tim loomed as a more impressive credential for Manny. Also, as part of a deal to secure the fight, Bradley agreed to a two-year extension of his promotional contract, which was due to expire in December 2014.

That said, the promotion was struggling a bit.

Elite fighters have a glow, an aura around them. Pacquiao in his prime was electrifying. But in recent years, the Pacquiao super nova has dimmed.

In the days leading up to Pacquiao-Bradley 2, the narrative was no longer about Manny’s Magical Adventure. The media no longer waited in heightened anticipation for his arrival at publicity events. The fighter himself seemed to have a bit of “Pacquiao fatigue.” Certainly, he was aware of the talk that his career was nearing an end.

Again and again during fight week, Manny told interviewers, “My time in boxing is not yet done. I want to prove that my journey in boxing will continue.”

There was the mandatory appearance by Pacquiao on Jimmy Kimmel Live and all of the ritual hype. But pay-per-view sales were tracking poorly, an estimated 650,000-to-700,000 buys (down from 875,000 for the first Pacquiao-Bradley fight). Ticket sales were respectable, but there wouldn’t be a sell-out.

It was Bradley who generated much of the energy in the media center. Tim is inherently likable with an exuberance for life and a smile that lights up a room when he enters. Insofar as his status as a role model is concerned, he and his wife, Monica, appear to have a loving stable marriage. When Bradley takes his children to school in the morning, it’s not a designed photo op for television cameras. There’s no bimbo girlfriend, no charge of domestic violence, no conspicuous spending. The thought of Tim blowing twenty thousand dollars in a strip club is ludicrous.

Bradley loves challenges. “I’m looking forward to the fight,” he told the media. “It will be fun.”

Reflecting on his football-playing days, Tim opined, “Boxing is more fun than playing quarterback. I like it better where, if someone hits me, I can hit him back.”

Defending the judges’ decision in Pacquiao-Bradley I, Tim told an interviewer, “Everybody has an opinion. That means I have an opinion too. Manny Pacquiao is one of the best fighters ever to lace on a pair of gloves. I’m a big fan of Manny Pacquiao. But I beat him.”

Then the interviewer stated proudly that he was rooting for Pacquiao, and Bradley responded, “If you’re a Pacquiao fan; hey, Manny is a good dude. I respect the person he is and I respect what he has done for the sport. I have no problem with anyone who roots for him.”

That left the trashtalking to Bob Arum, who spent much of the week denouncing the host site and the MGM Grand’s president of entertainment, Richard Sturm.

Arum was appropriately angry that the hotel-casino was festooned with advertising for the May 3 fight between Floyd Mayweather and Marcos Maidana to the detriment of his own promotion. Introducing Sturm at the final pre-fight press conference on Wednesday, he referenced the executive as “the president of hanging posters and decorations for the wrong fight.”

Then, at the end of the press conference, Arum went further, declaring, “I know the Venetian [which had hosted Pacquiao’s previous fight in Macau] would never make a mistake like this, They would know what fight was scheduled in three or four days, and they wouldn’t have a 12-to-1 fight all over the building that’s going to take place three weeks from Saturday. That’s why one company makes a billion dollars a quarter and the other hustles to pay it’s debt.”

The following day, Arum elaborated on that theme, telling reporters, “There are two companies which are the leadingAmerican companies in gaming, and it’s for a reason. It’s because they’re smarter than these guys and they know what they’re doing. First is the Venetian-Sands company and then there is the Wynn. Pick up a paper and look at where the stock of each company is going. Then tell me who has smarter people. Is it luck? I don’t think so. If one company is making so much more than the other company and doesn’t have financial problems because they borrowed too much money, it’s not luck. It’s because they’re smarter and conduct themselves better. This company really has a serious management problem.”

Thereafter, in various interviews, Arum called Sturm “a horse’s ass . . . totally clueless . . . a moron . . . a brain-dead moron,” and added, “He doesn’t have a fucking clue what the f— he’s doing.”

On Friday, the promoter proclaimed, “They [the MGM Grand] did something that I believe is an absolutely horrendous thing to do. It shows tremendous disrespect for the Filipino people, who are suchnice people. If I were Flipino, I would never patronize an MGM Hotel again.”

Then, as a helpful guide to Filipino high-rollers who might have been offended by the slight, Arum listed all of the MGM Grand properties that they might want to avoid in the future.

Meanwhile, the odds had settled on Pacquiao as a 9-to-5 favorite, down from 4-to-1 in the first Pacquiao-Bradley encounter.

Bradley has never been thought of as a big puncher. His ledger shows a meager twelve knockouts, with only one in the past seven years. Pacquiao, by contrast, has 38 career KOs. But Manny’s record is devoid of stoppages since his 2009 demolition of Miguel Cotto.

That led Bradley to declare, “Manny is still sensational physically, but I don’t think the fire is there anymore. He’s not the same fighter he used to be. He’s still a tremendous fighter. But the killer instinct, the hunger, is gone and it won’t come back again. Manny fights for the money. I have the hunger to win. I just feel that his heart isn’t in it anymore.”

Were Bradley’s comments about Pacquiao no longer having “killer instinct” designed to undermine Manny’s confidence? Or perhaps to goad him into fighting recklessly?

“Neither,” Tim answered. “I’m simpy stating a fact.”

Team Pacquiao didn’t entirely disagree with Bradley’s thought. Trainer Freddie Roach acknowledged, “Recently, Manny has felt it was enough to just win his fights. He didn’t want to hurt his opponent more than he had to. I’ve had a lot of talks with him about that and I’m sure it’s not going to happen again. When Bradley told Manny that he’d lost the killer instinct, frankly, Manny got pissed off. He thought it was disrespectful.”

“Sometimes I’m too nice to my opponent,” Pacquiao added. “I have been happy winning on points because it is winning. But the fans want to see that hunger from me, and I’m always concerned about the fans and their satisfaction. So I’m going to fight this fight to show that I still have that hunger and that killer instinct.”

But there were questions as to whether, intent aside, Pacquiao still had the strength and physical stamina to close the show against an elite opponent.

“To me, it’s not about killer instinct,” Joel Diaz noted. “I don’t think Pacquiao is being compassionate. I don’t think he can finish anymore. Look at what happened when he fought Marquez in their third fight. The judges scored it for Pacquiao, but a lot of people thought Marquez should have won. Everyone knew it was close. And Pacquiao couldn’t come on strong late. Pacquiao is getting older. He’s not the fighter he used to be in the second half of his fights.”

Bradley understands that there are no sure things in boxing. “I may lose this fight,” he said in a teleconference call. “You never know.Things happen in the ring when you least expect it.It only takes one punch to end the night.”

But as Pacquiao-Bradley 2 approached, Tim was confident, saying, “I’m a more mature fighter now than I was two years ago. I’m better at getting in and out on guys and controlling the distance between us, which I showed in the Marquez fight. I’m a better fighter now than I was the first time Pacquiao and I fought. And Manny can’t say that.”

“This is the first time I’ve fought the same guy twice,” Bradley continued. “And I think it’s an advantage for me. The first time we fought, I didn’t know how much intensity Manny brought to the ring. Omigod! He throws so many feints and closes the distance so fast and punches from all angles. He always keeps you guessing when he’s going to come in and out. Now I know what to expect. I was able to make adjustments in the first fight, and Manny had problems with me when I was moving. I’m excited; I’m happy. On Saturday night, I’ll get to show what I can do on the biggest stage possible. I know there are people who say I can’t hurt him. If Manny feels that way, let him come in reckless and see what happens.”

And there was another factor to consider. In his first fight against Pacquiao, Bradley had done something stupid. For the only time in his career, he’d entered the ring without socks because he’d once heard Mike Tyson say that going sockless helped him grip the canvas and increase the leverage on his punches. Bradley had trained sockless in the gym for that fight. But the canvas in the ring on fight night was different from the gym canvas. And the demands on fight night are different from the demands of sparring. In the early going against Pacquiao, Tim had suffered ligament damage in his left foot and sprained his right ankle.

“With two good feet, I’ll be able to move quicker this time and set down harder on my punches,” Bradley promised. “With two good feet, I can adjust my footwork to deal with whatever Pacquiao brings to the table. Pain-free is another dimension, and I’ll be pain-free this time.”

Indeed, the main concern in Bradley’s camp was that the judges might overcompensate for the perceived injustice of the scoring in Pacquiao-Bradley I and, fearing ridicule, have a default setting on close rounds in favor of Manny.

“We know the judges will have a lot of weight on their backs,” Joel Diaz noted. “The stage was set for Tim to lose the first fight, and it didn’t happen. Now the stage is set for Tim to lose again. If the fight goes the distance and it’s close, the judges will give it to Pacquiao. All I ask is for the judges to be fair. If Tim wins, give him the win. If Pacquiao wins, give him the win.”

Meanwhile, as the clock to fight night ticked down, it seemed as though Bradley had more enthusiasm for the battle than Pacquiao did.

“I got something to prove,” Tim declared. “I got something to prove to the media; I got something to prove to the fans; I got something to prove to everyone who says I didn’t win the first fight. This fight is redemption for me. I feel deep in my heart that I won the first fight and I didn’t get any credit. I’m going to beat Manny Pacquiao again. And this time, I want the credit for it.”

Team Pacquiao, of course, had a different view.

“Bradley is a very good fighter,” trainer Freddie Roach said. “He’s tough and resilient. He takes good shots.He has a good chin. He has determination and a lot of heart. When you hit him, he fights back.”

“But I don’t think Bradley has all the abilities that Manny has,” Roach continued. “He’s not as fast. He doesn’t punch as hard. When Manny is on his toes and uses his footspeed, he closes the distance better than any fighter in the world. Once you put Bradley on the ropes, his chin goes up in the air, he opens up, and he punches wild. When that happens, Manny can beat him down the middle. Once the scores have been announced and you’ve lost a fight, there’s nothing you can do about it except say, ‘We’ll get him next time.’ I think Manny beat this guy once, and I think he’ll beat him again.”

Pacquiao agreed with his mentor.

“I am impressed with what Bradley has done since our fight,” Manny acknowledged. “His style is hard to explain. He is not easy to beat. But I am still faster than Bradley and I still punch harder than Bradley. He says that he wants to see my killer instinct, so he will see it.”

Part Two of “Behind the Scenes at Pacquiao-Bradley 2” takes readers into Tim Bradley’s dressing room in the dramatic hours before and after the fight. It will be posted on The Sweet Science tomorrow.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

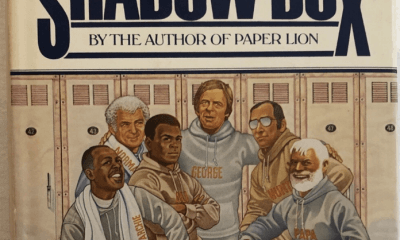

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates