Featured Articles

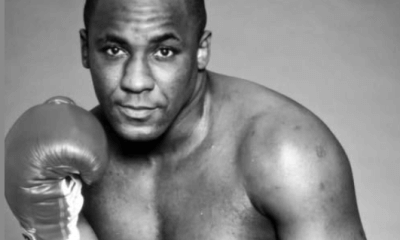

Mike Jones Returns in Search Of Lost Spotlight

Out of sight, out of mind.

It is the fear of losing their celebrity, or at least at some measure of relevance, that apparently spurs the Kardashian sisters to relentlessly pursue anyone with a camera or a microphone willing to document their latest exploits. In a media-driven world, possession of an actual talent apparently is not required for shameless wannabes to become rich and kind of famous.

But the turning off or misdirection of the spotlight has an even more deleterious effect on those with a truly special skill-set. WBA super middleweight champion Andre Ward is widely regarded as the finest pound-for-pound fighter on the planet not named Floyd Mayweather Jr., and there are those who would argue he’d be at the summit of the pugilistic mountain now if he were fighting more often. But injury (surgery on his right shoulder in January 2013) and a contractual dispute with his promoter, Dan Goossen, have kept Ward off to the side instead of in the ring. The likelihood of a drawn-out litigation to resolve the matter – the Oakland, Calif., native hasn’t fought since defending his title on a unanimous decision over Edwin Rodriguez on Nov. 16, 2013 – is, at 30, putting on hold too long a stretch of his prime. And time, precious time, is something no boxer, especially the special ones, can afford to waste.

Former welterweight contender Mike Jones (26-1, 19 KOs) is not Andre Ward. He is not now nor has ever been on any pound-for-pound lists. But the lean Philadelphian rose to No. 1 in the WBO rankings not so very long ago, and no lower than No. 3 in any of the other three so-called major sanctioning bodies. He was far ahead on points on all three judges’ scorecards in his bout with a faded but still-dangerous former WBO junior welterweight champion, Randall Bailey, in their matchup for the vacant IBF 147-pound title on June 9, 2012, at Las Vegas’ MGM Grand, when he was knocked out by a ripping right uppercut in the 11th round.

Had he avoided that big shot (he also went down in the 10th round) and made it to the final bell, Jones – who was and still is co-promoted by Top Rank, in conjunction with Philly-based J Russell Peltz – might have been in line for a high-paying, high-visibility matchup with Filipino superstar Manny Pacquiao, the undisputed lead attraction in Top Rank’s stable. And even if he didn’t snag that plum assignment (no one was apt to nominate Jones-Bailey for Fight of the Year), as a new champion he was assured of a nice consolation prize.

“As bad as the fight was with Bailey – as boring, as monotonous as it was – he was 3 minutes and 8 seconds from at least a half-million-dollar payday overseas with England’s Kell Brook,” Peltz said a few days after Jones’ “comeback” bout, against Jaime Herrera on Aug. 23 at Bally’s Atlantic City, was announced. “And when you see how they’re always scrambling (to come up with acceptable opponents for Pacquiao), Mike would have had to fit in there somewhere.

“But you’re only as good as your last fight. If only Mike had won, he could have capitalized on that. But when your previous few fights were tedious also, it’s harder to do that. Top Rank invested a lot of money in him. They put him on three of the biggest stages you could put a fighter on – Cowboys Stadium, Madison Square Garden and the MGM Grand. Come on, fighters dream of that. And he didn’t come through on any of those big stages.”

Jones is 31, older than Ward, and he’s been off longer. It will be 26 months before he steps inside the ropes against Herrera, not exactly an eternity but a long enough period of inactivity to expunge him from every alphabet organization’s ratings for inactivity and for him to collect at least a veneer of ring rust. Nor can Jones pin at least part of the layoff on injury; he does not have a note from his doctor to explain why he has virtually disappeared from public consciousness.

“(Top Rank officials) told me, `Russell, you get him a comeback fight,’” Peltz said. “But Mike has been stubborn. He was all ready to sign a year ago to fight in Atlantic City, but it fell out over a contract squabble with (co-managers) Doc (Nowicki) and Jimmy Williams.”

Whether Jones’ return to action is cause for the renewal of high expectations is a matter of some conjecture. He will be favored to win, and look good in doing it, against the 25-year-old Herrera (11-2, 6 KOs), but even if he does it will not make for a dramatic announcement that he is indeed back. Jones needs to make up for lost time, and in a hurry. He said a more regular slate of ring dates, against an increasingly higher level of opponent, will restore the luster to his damaged image. Destiny delayed is not necessarily destiny denied.

“I would say just being busier,” he said when asked what it would take to re-enter the ratings and to reclaim as much of his receded prestige as possible. “I just need to get some fights, to get back in the groove of things. Once that happens, I’ll be back where I’m supposed to be.”

If everything does begin to fall into place, it will be because Jones – who relocated to Henderson, Nev., just outside of Las Vegas, only weeks after his loss to Bailey – will have a new look, a new style. Which is to say it will be his old style, the one that he made the mistake of abandoning once he began to gain prominence.

The Mike Jones that grabbed fight fans’ attention was the one who mowed through a succession of designated victims at the New Alhambra in South Philadelphia, now known as the 2300 Arena. He was a compelling local story, a father of two young daughters who helped make ends meet by working part-time as a forklift operator at the Home Depot in Cherry Hill, N.J., when he wasn’t knocking guys stiff in the 1,100-seat bandbox where he made his reputation. Of his 12 bouts at the New Alhambra, Jones won 11 inside the distance, often in spectacular fashion. It was what was to be expected of someone whose first boxing mentor was the late, great former heavyweight champion, “Smokin’” Joe Frazier.

“Joe wanted all his guys to be modeled after him,” Jones said before his Dec. 3, 2011, bout with Sebastian Lujan at Madison Square Garden, a month after Frazier’s death following a prolonged bout with liver cancer. “He’d say, `You want to plant those feet and get those knockouts. Be grounded and have that foundation first. Sit in the pocket and really dig it out.’”

Even then, though, Jones was beginning to hold something back, increasingly playing it cautious instead of really digging it out and going for the knockouts so prized by Smokin’ Joe. He had risen too far, he figured, to be taking foolish chances and to expose himself to a defeat which could send him back to the New Alhambra. Top Rank chairman Bob Arum was grooming him for stardom, wasn’t he? When he came in as Peltz’s promotional partner on Jones, Arum had said, “We really like Jones. We think he’s a major talent. He represents the future of the welterweight division.”

“Some guys just fight to get the victory,” Jones said in acknowledging the metamorphosis of style that would prove so detrimental. “Some guys put their heart and soul into every fight. That’s how I began in this game. I lost it little by little as I started to get more successful. I was fighting not to lose instead of letting it go and fighting to win.

“Before, I always went for the knockout. That’s just the kind of fighter I was. But you know what? I’m still that kind of fighter. I definitely want to get back to fighting that way. I know I can do it.”

Peltz, who again is charged with the task of helping Jones further his now-stalled career (Top Rank, for now, is more or less sitting things out), hopes that the words aren’t merely hollow promises. He knew what he had in rising star Jones, and he said it was something that excited him to a degree he hadn’t felt in some time.

“I thought Mike Jones singlehandedly was going to revive boxing in Philly at a major level, the way his career started out,” said Peltz, who was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2004 and who has promoted, among others, fellow Hall of Famers Matthew Saad Muhammad and Jeff Chandler. Before the Lujan fight – a desultory, 12-round decision that was televised by HBO – Peltz had offered the opinion that Jones “has a chance to be a megastar. I’m looking for this kid to get it all.”

And now?

Arum, who is recovering from knee-replacement surgery, was unavailable for comment, but Carl Moretti, Top Rank’s vice president of boxing operations, issued something less than a full-fledged endorsement of Jones as the growth property he was once considered to be.

“It remains to be seen if he can get back to where he was,” Moretti said. “I don’t know if it was really anywhere to get back to. He fought on HBO a couple of times and didn’t exactly light it up. Depending on how he does and how active he is, that will determine how far he can go. But there’s no question it’s an uphill road.”

Added Peltz: “Mike’s been his own worst enemy for the past two years. I try not to believe what I read on the Internet, but from the few stories I’ve seen he’s not happy with anybody. There’s nothing in my contract with Mike Jones that says we have to like each other.”

The wild card in the deck is the very real possibility of lawyers getting involved. After Jones and Herrera duke it out, the next round could be fought in a court of law by attorney Eric Melzer, who represents Jones (as well as Bernard Hopkins) and Nowicki’s lawyer, Joe Grimes. If a lawsuit is filed and a settlement not reached, Jones’ return could again be put on hold.

“Almost every fighter I’ve had, when the end of their contract is coming up, thinks that somebody else is going to do better for them,” said Nowicki, who detailed all he had allegedly done for Jones above and beyond the functions a manager normally would be expected to provide. “When you get a guy to a shot for a world title, when that guy is climbing up the ladder, everybody wants to be his friend, everybody’s telling him how great he is. They think he’s making millions of dollars.

“Look, if he doesn’t want me to be his manager, I certainly don’t want to be associated with somebody that doesn’t want to be associated with me. But I’ll be damned if I have a deal with somebody and then they try to tell me there is no deal. I’ll probably have to take him to court.”

Jones, who said he has no manager now and doesn’t intend to take one on, disputes Nowicki’s claims.

“My position is that no valid contract exists because it wasn’t signed in front of a commission,” he said. (EDITOR NOTE: Who can weigh in here and offer a guesstimate on how many such deals ARE signed in front of a commission?) “If everybody’s not working in perfect harmony, you should split and go someplace where you’re more appreciated. Have a new beginning. It’s no good when everybody’s not on the same page.”

It’s a familiar tale in boxing, one side saying A-B-C, the other saying X-Y-Z. Sometimes the right and the wrong of it is starkly black or white, right or wrong. Other times, not so much. Shades of gray exist that must be interpreted and ruled upon by a judge or an arbitrator. For now, though, Jones would like to have another chance to compare notes with Ward, who, in his role as an HBO analyst, spoke to him in the ring after Jones’ rematch victory over Jesus Soto-Karass on Feb. 19, 2011.

“He just talked to me about the fight,” Jones recalled. “I think we’d have a lot more to talk about now.”

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoA Night of Mismatches Turns Topsy-Turvy at Mandalay Bay; Resendiz Shocks Plant

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering the Under-Appreciated “Body Snatcher” Mike McCallum, a Consummate Pro

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books