Featured Articles

KELLIE BY KO Promoter Frank Maloney Stuns The Fight World

The revelation, delivered in a Brit tabloid on Saturday, does make one who knew Frank Maloney when he was a top-dog boxing manager and promoter in the UK, heading up Lennox Lewis’ promotions re-evaluate who he was, how he acted, what he said, back in the day.

When Maloney drew a deep gulp of breath, and shared with the world that he has really basically always felt like he was a female trapped in the shell of a man’s body, the legendary fightmakers’ legacy veered sharply, from that of a Hall of Fame level mover of pugilists and marketing and salesmanship and such, into a whole ‘nother realm.

When the person formerly referred to as “Frank Maloney” allowed a photog to take some photos that showed off, to a world he had to know wouldn’t be universally embracing of his choice, his new look, and his new identity, which he told us is “Kellie,” the man showed as much courage as any of his boxers did walking up those four steps toward an uncertain fate.

The 63-year-old Maloney, who many US fight fans might remember as a smallish fellow who’d stand and exult by the side of Lennox Lewis as the long, tall Brit of Jamaican heritage showed off his stuff and had his hand raised in triumph, downing the likes of Evander Holyfield while advertising proudly his homebase in a Union Jack blazer and slacks outfit, told the Sunday Mirror that he’s been taking female hormones for about two years.

“I was born in the wrong body and I have always known I was a woman,” the 5-3 Maloney, aka “Kellie,” told the paper. “I can’t keep living in the shadows, that is why I am doing what I am today. Living with the burden any longer would have killed me.”

The dealmaker, who walked away from the sport last year, citing burnout, said he had a hard time living a lie, and grew quite depressed, and self medicated his sorrows with booze. When assessing his life arc, one can now look at Maloney’s chapters, and be tempted to ponder what choices he made under the influence of his hidden duress.

Younger Maloney contemplated the priesthood but didn’t cotton to a stint at a seminary. He tried the jockey life, gave football a go, tried cooking as a trade, but all along, he stuck with the boxing thing, after taking it up in grade school. Makes sense, we all understand that the sport, with its low barrier to entry, attracts square pegs and drifters and loners and even the most refined and mannered and psychologically grounded, to boot…

Armchair analysis aside, Maloney and Lewis worked together and got along well enough that they partnered from 1989, when LL debuted as a pro, til 2001. Maloney’s star brightened immensely when Lewis was handed the WBC crown Riddick Bowe dumped in a trash bin, in December 1992. The diminutive Maloney showed a big bark and could bite when defending Lewis, who naysayers sometimes said fought too cautiously. He drew sympathy when he absorbed the slurs from the likes of Don King, who termed him a “mental midget” and in fact gave Maloney a free boost in recognition a $100,000 retainer to a top firm couldn’t have managed.

The 6-5 Lewis, now 48, stood up for the helmer, taking to Facebook to post his support for the ex manager’s new path. On Sunday, Lewis wrote, “I was just as shocked as anyone at the news about my former promoter and my initial thought was that it was a wind up. The great thing about life, and boxing, is that, day to day, you never know what to expect. This world we live in isn’t always cut and dried or black and white, and coming from the boxing fraternity, I can only imagine what a difficult decision this must be for Kellie (formerly Frank Maloney). ?However, having taken some time to read Kellie’s statements, I understand better what she, and others in similar situations, are going through. I think that ALL people should be allowed to live their lives in a way that brings them harmony and inner peace. I respect Kellie’s decision and say that if this is what brings about true happiness in her life, than so be it. #LiveAndLetLive.”

Maloney’s last top drawer client was heavyweight David Price. Last October, the boxing lifer exited the sphere, saying, “For the last year I have gradually fallen out of love with boxing and my passion has been missing. I did much soul searching over the summer and my heart is no longer in the sport that I loved so much. If I continued as his promoter it would be unfair as I cannot give the commitment and love for the sport that is needed to get his career back on track. When I saw (Price) in the gym last week it was my first visit to one for months and I no longer got the buzz I used to get. The sport has changed so much over the last few years. So many boxers listen to the last person they meet, and trainers who give time but invest no money into the sport are afforded too much power. It has also been a tough time for me personally and I feel a lot more at ease with myself by reaching this decision.”

At the time, I thought it…odd…that he put the word out that he didn’t want to be bothered, and wanted to simply step away, and let that statement speak for him. No interviews or requests to chat about legacy or such, he said. Now we know better why, I suppose…

Maloney is not to be confused with the still-in-the-game Frank, Frank Warren, the head of Box Nation, who has a smaller than it used to be but still respectable stable. He and Maloney sparred regularly, and then would make up, and do some business together. Maloney took one to the chin and heart when his boxer Paul Ingle was brain damaged in a 2000 bout. But he kept at it in this most dangerous game, though his fondness was dealt a blow when he and Lewis parted ways in fall 2001. There was friction in the partnership when Lewis lost his crown to Hasim Rahman in April 2001, as trainer Emanuel Steward said Maloney has been too MIA when it came to Lewis. Maloney shifted his gears and took up politics, running for the Mayoral seat in London. He stepped in when he went on the attack against gays, in 2004, saying, “I don’t (gay people) do a lot for society. I don’t have a problem with gays, what I have a problem with is them openly flaunting their sexuality…I’m more for traditional family values and family life. I’m anti same-sex marriages and I’m anti same-sex families….I don’t think it’s right for children to be brought up that way. I don’t think two men can bring up a child. ..If you are homosexual, you are homosexual – just get on with your life and stop bitching about things.” He finished fourth in the Mayoral hunt. By 2006, he was back all-limbs in the boxing waters, getting then cruiserweight David Haye to sign on, while also steering feather Scott Harrison to a title. He was tested in 2009, when he had a heart attack after finding his boxer, Irishman Darren Sutherland, dead from hanging in the fighters’ apartment. His split from second wife Tracey, at the end of 2012, took something from him, as well.

Maybe he was feeling some tension from home stuff when he made the beyond-tasteless crack that Wladimir Klitschko was probably happy he didn’t have to pay a trainer cut to Emanuel Steward for his fight against Mariusz Wach in November 2012, soon after Steward passed away. In October of 2013, Maloney had enough, and waved adieu to the sport.

Maloney’s decision will bring up recollections and discussions of the former Richard Raskind. The New York born Raskind was a tennis ace, and showed off mad racquet skills at Yale. Raskind went into opthamology, but gender orientation issues plagued him, and by 1975, he was a she. As “Renee Richards,” she sued to be able t play in the US Open. She won, and rose as high as 22 in the ranks on the pro women’s circuit. It is clear that such decisions and stories as this Maloney development aren’t happening in a vacuum. The boxing family warmly embraced Orlando Cruz, who came out as a proud homosexual in October 2012, and while there were the odd Twitter cracks by lunkheads, as we’ve seen in reaction to the “Maloney-Kellie” affair, the buzz stirred up lasts less and less every time a Jason Collins (NBA, came out April 2013 to the world) or Michael Sam (NFL, came out as gay in Feb. 2014) break new ground.

Maloney said in the Mirror stunner that he isn’t in a mode to think about a romantic romp or anything of the sort. The now avowed transsexual was twice married and has three children.

To wrap up, I will leave it to Lewis, who threw a tight flurry on Facebook, stating, to those getting wound up over the Maloney-to-Kellie deal, “There are more important things in this crazy world 2b mad about! Starving children, poverty, conflict. LeBron leaving Miami.”

Amen, Lennox. I wish Kellie nothing but the best of luck, and admire the ration of gumption it took to surrender to the truth.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

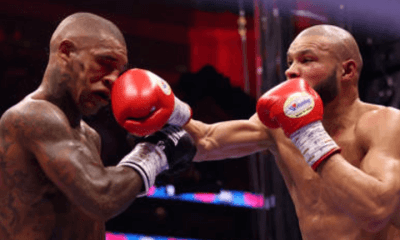

Featured Articles4 weeks agoChris Eubank Jr Outlasts Conor Benn at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

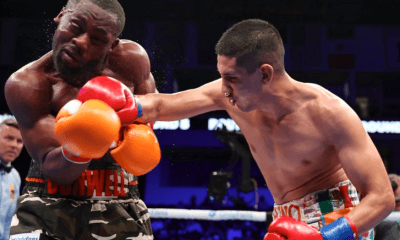

Featured Articles3 weeks agoJorge Garcia is the TSS Fighter of the Month for April

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

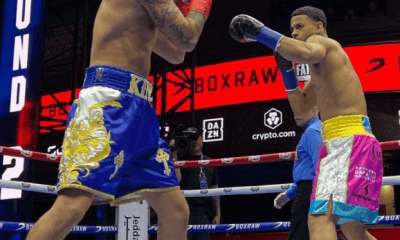

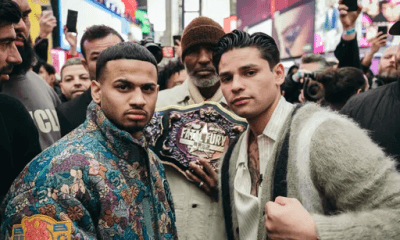

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRolly Romero Upsets Ryan Garcia in the Finale of a Times Square Tripleheader

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 324: Ryan Garcia Leads Three Days in May Battles

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCanelo Alvarez Upends Dancing Machine William Scull in Saudi Arabia

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoUndercard Results and Recaps from the Inoue-Cardenas Show in Las Vegas

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoBombs Away in Las Vegas where Inoue and Espinoza Scored Smashing Triumphs

1 Comment