Featured Articles

Why ‘The Old Mongoose’ Means So Much To Me

The framed poster, from a fight card staged on Aug. 18, 1944, in San Diego, Calif., had yet to be picked up by its owner from the custom frame shop in the leafy Philadelphia suburb of Bryn Mawr, Pa. It was lying against a wall behind the counter when Philly-based promoter J Russell Peltz, an avid collector of vintage boxing memorabilia, saw it and decided it would make a nice addition. So he asked the proprietor, who did all of Peltz’s framing, to whom the poster in question belonged.

As it turned out, I was that owner. Ironically, it had been Peltz who, in response to a question I had posed to him several days earlier, had suggested I bring a boxing item that was near and dear to me to that particular shop.

“I’ll give you $300 for that poster,” Peltz told me the next time we spoke. I presume his offer was in addition to the cost of the framing, which was a bit pricier than what you might expect at a shopping-mall frame shop.

“Not for $300,” I told him. “And not for $3,000.”

Probably not for $30,000, either, although in these difficult economic times, I might have had to consider an offer so exorbitant that no memorabilia collector in his right mind, unless he was Bill Gates, Warren Buffett or George Steinbrenner, would have made. But this poster was special to me, and not just because the main event, in large block print, hyped a main event in which evolving legend Archie Moore was to take on Jimmie Hayden.

It was a name, in smaller print, listed below “The Old Mongoose’s” that set this poster apart for me from so many others made distinguished by the Hall of Fame-level fighters at the top of the card. Two bouts – listed by promoter Onyx Roach as “Double Semi-Final –Each 6 Rounds” — advised would-be attendees that Bill Campbell was be swap punches with Kid Hermsilla, and that Jack Fernandez was paired with Jimmy Hatmaker.

Jack Fernandez’s given name was, in fact, Bernard J. Fernandez. The eighth of eight children born to Lillie Fernandez and her husband Emile Fernandez Sr., Jack’s lengthy and quite accomplished amateur career was forged in large part during the Great Depression, as was the case with so many fighters in those days. His nickname was conferred upon him by observers who thought his crouching, attacking style was somewhat reminiscent of Jack Dempsey’s, and his many friends continued to call him Jack until his death, at 74, on March 4, 1994. For purposes of this story, let it be noted that the fighter’s full name underwent a slight renovation when he became Bernard J. Fernandez Sr., after his only child, a son, was born amidst the howling winds and flooding storm surge of a hurricane (the National Weather Service had yet to begin naming them) that struck Jack’s hometown of New Orleans, La., on Sept. 21, 1947.

That poster is not the only memento I have of my father’s brief professional boxing career, but it is the most treasured and now something of a family heirloom, to be passed down to one of my two sons after I, too, receive the eternal 10-count. There also is a belt buckle with Jack’s name engraved on it, for winning an amateur tournament of some importance in New Orleans, and a raft of yellowing newspaper clippings that have had to serve as the only portals I have into his boxing past, as there are, to the best of my knowledge, no tapes or film clips existing of his six pro bouts (final record: 4-1-1, with one knockout victory). One clipping tells the tale of Jack, then in the Navy and in training in Corpus Christi, Texas, for his World War II sea duties, scoring an electrifying knockout victory over a local fighter, Manny Gonzales.

“Fernandez, fighting in a crouch, literally won the fight with the first punch he threw – a stunning left hook to the jaw – which sent his opponent crashing to the floor for the count of nine,” the story recounted. “Fernandez’s sharp left hooks and powerful rights found their mark repeatedly the remainder of the first round and only the sheer gameness enabled the Corpus Christi idol to last the round.

“Early in the second round Fernandez floored his foe again with a hard right to the left ear. Gonzalez staggered up at the nine count, but the New Orleans slugger tore in for the kill and finished the fight with a right smack flush on his opponent’s jaw.”

Another article, written for a New Orleans newspaper by the paper’s future sports editor, Art Burke, who also was serving in the Navy, read, in part:

“We had a monthly `smoker’ here at the gymnasium (in San Diego) Wednesday (which opened with the returns of the Conn-Louis fight) and one of our New Orleans Reservists, Jack Fernandez, fought on the eight-bout boxing program and scored the only clean-cut knockout of the night. You may remember this boy since he reached the semifinals of the Sugar Bowl boxing tournament in 1940. His victory was all the more thrilling by the fact that the boy he kayoed in the second round was Utah state champion for three straight years and had not been knocked out in 75 fights.”

Perhaps, had he not spent the better part of four years in a desperate fight to avoid being killed by the Japanese Imperial Navy during World War II, Jack might have had more than the few pro bouts he accepted when his damaged ship, a destroyer escort, was in San Diego and being refitted for combat. Perhaps he might have fulfilled the ring promise so many believed he had until the bombing at Pearl Harbor changed everything for millions of Americans.

Then again, my dad was a realist. His window of opportunity as a fighter had closed, or at least was closing, and, besides, his fiancee – that would be my mother – didn’t want him to expose himself to further danger, as would be posed by opponents’ gloved fists. So upon his return from WWII Jack promised her that he would give up boxing and take up a safer pursuit, which turned out to be a 27-year career with the New Orleans Police Department, where he might – and did – occasionally come up against armed felons. Go figure.

I always think of my father – well, at least more than usual – in March, around the anniversary of his death, as well as in June, when the annual International Boxing Hall of Fame induction weekend is staged, and in December, because that is a month that has special significance to me because of his link, however tenuous, to the great Archie Moore. They appeared on the same card just that once, Archie knocking out Hayden in three rounds while my dad – in his final pro bout — and Hatmaker had to settle for a one-round technical draw after an inadvertent clash of heads left both men with nasty gashes that left them unable to continue, at least in the eyes of the ring physician or the referee, as the case may be.

As a child who worshipped his father, and came to love boxing because he loved it so, I remember asking him if he knew Archie Moore, given a moment in time when they shared the same stage at more or less the same time. Jack said no, that the Mongoose was probably having his hands wrapped when he and Hatmaker were butting heads like frisky mountain goats. But I always chose to believe that Archie had slipped out of his dressing room to catch a glimpse of the left-hooking sailor from New Orleans who, in my mind, surely was winning his bout with Hatmaker until the inopportune butt deprived him of the victory to which he surely headed.

Many years later, when Moore was training George Foreman in the second stage of Big George’s remarkable career, I might have had the opportunity to query him about that long-ago August night in San Diego. But those interviews were always in group sessions, with other reporters present, and I thought it unseemly to take up part of the available time with so personal a question. Then again, it could be I just preferred to preserve my own wishful version of what had or hadn’t happened. And in that version, Archie Moore was as big a fan of Jack Fernandez as Jack Fernandez was of Archie Moore.

Until the day he died (more on that a bit later), my father always contended that I had achieved more in boxing that he ever had. It was, of course, a crock. He made his mark with blood and sweat and the kind of courage all fighters have to find within themselves when the going gets tough, while I typed away on a portable word processor, crafting stories about individuals who risked so much more than I ever had, or ever could. Jack was my hero, my role model, and a better man than I was then, or am now.

To repay the debt I always believed I owed him, for basically giving me my career as a boxing writer born of together watching so many “Gillette Cavalcade of Sports” TV fights on Friday nights on our little black-and-white home screen, I flew dad to London, his only trip to Europe, for the Lennox Lewis-Razor Ruddock fight on Oct. 31, 1992. He also accompanied me to Las Vegas, for the rematch of Mike Tyson and Razor Ruddock on June 28, 1991. They were the kind of big fights, on brightly lit stages, that I suspect he always hoped would have been his destiny under different circumstances.

TSS readers know that I sometimes write about the anniversary dates of certain fights that should be remembered regardless of how much time has passed since they occurred. In recent months I have authored pieces on Rocky Marciano and the Spinks brothers, among others. It is perhaps a concession to my senior-citizen status that I more cherish the memory of classic bouts in my rear-view mirror than some that will or might happen in the future. When I sat down to write this piece, it was to have been about watershed events that took place in December during Archie Moore’s long march into boxing history: His death on Dec. 9, 1998, in San Diego; his 11th-round knockout of Yvon Durelle in Montreal on Dec. 10, 1958, an electrifying rally in which the Mongoose weathered four knockdowns before turning the tide, and his long-delayed winning of the light heavyweight title, after 16 years as a pro, on Dec. 17, 1952, when he outpointed Joey Maxim over 15 rounds in St. Louis, Mo.

Then I looked up at the poster hanging in my home office, and my approach changed, something akin to Muhammad Ali deciding on his own that what later came to be known as the “rope-a-dope” might work better against the heavily favored George Foreman in Zaire than the presumably more sensible stick-and-move strategy that had been laid out by trainer Angelo Dundee.

The International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Class of 2015 was announced on Thursday, which also has special significance to me because there wouldn’t even be an IBHOF in Canastota, N.Y., were it not for the fact that that central New York village’s favorite son is the late, great Carmen Basilio, who happened to be Jack’s favorite fighter in the 1950s. It stood to reason that Basilio was my favorite fighter, too, during my early grade-school years, with Jack and I cheering him from the semi-comfort of our cramped living room whenever the “Onion Farmer” was appearing on those Friday Night Fights telecasts.

Canastota also was a favored destination of my dear friend Angelo Dundee, who was to the IBHOF what the Pied Piper of Hamelin was to the children who were so drawn to the sounds of his magic flute. Every time Angelo, who died on Feb. 1, 2012, returned for IBHOF induction weekend, fight fans surrounded him, in part because of who he was and what he meant to boxing, but also because even in a minute of pleasant conversation he could make everyone he encountered feel like a friend of long-standing.

Jack had his own moment with Angelo, which actually was an hour and a half in duration. During the trip my dad and I made to London for Lewis-Ruddock, we came down for breakfast at the White House Hotel in the Kensington section and ran into Angelo, who was also staying there. The three of us shared a table, ate a little and talked a lot, with Jack and Angelo exchanging tales, as fight people are wont to do. Angelo’s two most famous pupils, Ali and Sugar Ray Leonard, were topics of discussion, but not as much as Basilio and two champion fighters from New Orleans Ange had also worked with, Ralph Dupas and Willie Pastrano. It was the happiest I had seen my dad during that trip; by then his legs were giving him trouble, he tired easily and he either couldn’t complete or begged out of standard sightseeing ventures to the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey and the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace.

Whenever I’d speak to Angelo thereafter, he inquired after Jack. One day in 1994, however, I had to tell him that my father had passed away, during the last and worst of his several hospitalizations for cardiac problems. My mom, Alice, had called to say that I needed to get to New Orleans as quickly as I could, that this one was serious. The emergency trip from Philadelphia lasted the better part of six hours before I made it to East Jefferson General for what would prove to be the last hour of Jack’s life. It was then that I was informed that my father, in terrible pain, had refused medication that would have eased his suffering because he didn’t want to be unconscious or unresponsive when his son made it to his bedside. To this day I am convinced he held on in those figurative championship rounds until I got there.

As I recounted the particulars of Jack’s most heroic battle, which he lost only on the ultimate judge’s scorecard, the usually upbeat Angelo turned serious. “I’m not surprised,” he told me. “Your dad was a fighter.”

So it doesn’t matter much whether Archie Moore and Jack Fernandez actually met. They probably didn’t, and I know for sure Jack and Carmen Basilio never spoke. To me, they, and Angelo, are all part of a broader mosaic that comprises the fabric of my life. As far as visitors to the IBHOF are concerned, only Archie, Carmen and Angelo are Hall of Famers. Most wouldn’t have a clue that a fighter named Jack Fernandez ever existed.

But a plaque on a wall shouldn’t be all there is to certify a Hall of Fame life. As I look upon the framed poster that is at once my proudest possession and the standard of personal conduct to which I constantly aspire, I understand that some memories can’t, and shouldn’t, come with an attached price tag.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

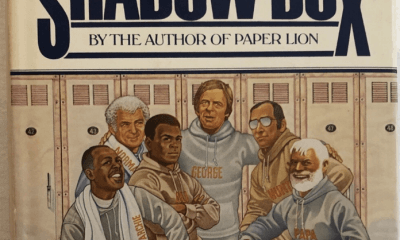

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates