Featured Articles

The Heavyweight Bogeyman

When a heavyweight is defeated in the manner that undisputed heavyweight #1 Wladimir Klitschko defeated Alexander Povetkin at the end of 2013, he usually has the good grace to disappear.

Ernie Terrell went 7-4 after Ali spent fifteen rounds turning his face into luncheon meat in their infamous “what’s my name!” encounter from 1967; behind the hideous beating he absorbed against a furious Rocky Marciano in their 1953 rematch, the excellent Roland LaStarza managed just 3-4 before hanging them up for good.

It is physical, yes.

Professional athletes of this standard, whether they are a surgeon of Ali’s calibre or a cannonball of Marciano’s density, do damage. They shift organs. They grind bone. But it is also psychological. Fighters, in reaching the summit of their personal Everest only to be confronted by an animal so in excess of their own evolutionary prism that they are, in essence, chanceless, perhaps don’t want to climb again. Every blow absorbed, every meal missed, every first step taken by a toddler to whom the fighter is a stranger, is for a reason in the beginning – The Title, The Title, but when The Title seems no longer a possibility it becomes easier to stay down, to clinch instead of punch, to run instead of box. Terrell and LaStarza found the end of their string in the ring of the dominant champion that bloodied their respective eras, and with that string providing a definitive measurement of their abilities, certain realities had to be accepted.

Yesterday in Moscow, Povetkin reversed this trend, finalising his rehabilitation with a sensational first round knockout over #10 heavyweight Mike Perez.

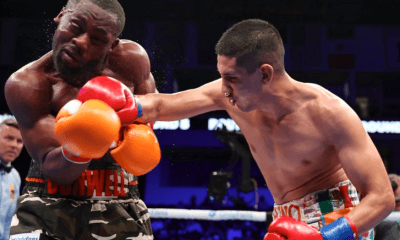

Perez is an impressive scalp almost regardless of circumstances. A superb body-puncher capable of deploying a high workrate (when he’s in the mood), Perez is a rarity in the modern heavyweight division on two different scores and his technical gifts and counter-punching ability certainly put him in the “handful for anyone” category despite certain doubts concerning his temperament (and his commitment to training). These doubts deepened after the injury tragically inflicted upon Magomed Abdusalamov by Perez during their rousing 2013 encounter in New York. In the wake of this contest, doubts surrounding Perez’s already questionable temperament deepened, but he was desperately unlucky against Bryant Jennings the following summer, missing out on a draw by virtue only of a point deduction in the final round. Jennings had been pushed to the absolute brink by a more talented fighter who could not match his athleticism. That said, Jennings adapted superbly, eschewing his reach advantage to come inside and make a fight of it after being cleanly out-boxed over the first three rounds.

Neither man was disgraced in that contest, but what it meant for Perez was that he was to enter his showdown with Alexander Povetkin last night in Moscow with, having knocked out cruiserweight journeyman Darnell Wilson in two rounds earlier this year, and drawn with the ranked Carlos Takam in January of last year, a 1-1-1 ledger for 2014 and 2015. Despite the bad luck, tragedy and slick counter-punching that had defined his previous 30 months in the ring, a loss would have sent Perez bumping roughly down the ladder to gatekeeper status.

More shockingly, a loss would have had the same impact upon Povetkin.

Re-watching Perez-Jenkins this morning, I was struck by how efficiently Harvey Dock managed the Cuban’s fouling early in the fight. Every time, without exception, that Perez placed his forearm or any weight across the American’s neck or back, the referee stepped in to separate the two. What would Povetkin have given for such a referee the night of his contest with Wladimir Klitschko?

Luis Pabon was the third man in the ring the night of Povetkin’s shot at king Klitschko, and as the champion over and over again drew the Russian in with his enormous reach before placing his full 241lbs on the smaller man’s back, crushing him, literally, with his superior size, the referee neglected to act. It was an exhausted Povetkin who was repeatedly barrelled to the canvas by the champion as the fight descended into a physical and technical mis-match. Much spleen was vented in the aftermath concerning Wladimir’s solution to Povetkin’s rushing tactics, but the scorecards of the three judges, bereft of any instruction from Pabon to remove any points from Wladimir’s total, sang out their scores as a choir: 119-104. Povetkin had been outclassed and had absorbed a horrific beating in the process.

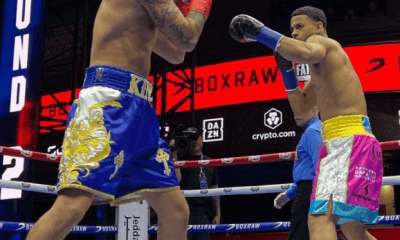

When he returned, Povetkin did so against the perfect opponent, Manuel Charr. The enormous Lebanese, who boxes out of Germany, was neither ranked nor particularly dangerous, but he was known, courtesy of his crack at Vitali Klitschko’s alphabet strap, and he was durable. He promised a comeback victory and a good workout. Povetkin’s triumph was no surprise but the manner, perhaps, was. Charr, who had been stopped just once on a cut, was blasted out in seven, the finishing left-hook/right-hand combination so spectacular as to remind one of Joe Braddock’s near decapitation at the hands of Joe Louis. Returning to ranked competition, Povetkin did a similar job on Carlos Takam, dropping him in the ninth, following fluid combinations with a monster right hand, before landing a glorious left hook to end proceedings in the tenth.

This performance pricked my ears a little; Povetkin, perhaps, was not going to go the way of Terrell and LaStarza. But what was his role to be? That was decided in last night’s contest with Mike Perez.

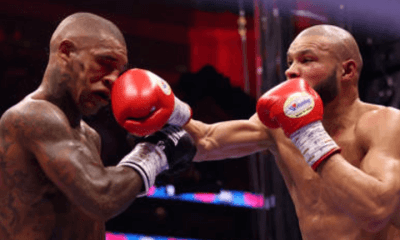

Perez came out showing measured aggression, probing with the jab before launching a two-handed attack over the top. Povetkin gave ground and then re-took his territory in the middle of the ring. When he threw his first one-two it was clear that Perez was surprised by the speed with which Povetkin punched; he made no attempt to counter. When, after leading with his own one-two seconds later he was caught by a lightning-fast right-hand to the top of the head, Perez lost his feet. He stammered backwards, hurt, and not just physically but neurologically – he was suffering not from messages of pain but from messages of disaster, his nerve endings alerting his brain to the fact that he no longer had complete control over his body.

It is worth reiterating at this point that Perez, like Charr, like Takam, has never been stopped; his chin was tested by Magomed Abdusalamov, among the hardest punchers in the division when he repeatedly reached the Cuban’s chin; Jennings, too, repeatedly landed clean, crisp shots to little affect. But here was Perez, grasping for the canvas. Seconds later, when Povetkin stepped out of a half clinch to give himself room for the shortest of right hands, Perez was suddenly on the ground looking up. Closed-faced, he defeated the count, and stepped tenderly towards the gallows. A sweeping left sent Perez crashing into the ropes and out of the rankings and made Povetkin once more the preeminent heavyweight in the world with a name other than Klitschko.

Generationally, it makes no sense. On paper, Povetkin’s time had come and gone. In reality, he looks better than he did before Wladimir beat the contendership out of him. He almost looks faster but in reality it is a new sharpness that appears to have gripped his offense. The punches that Povetkin is throwing are absolutely deadly.

His ability to absorb the beating that Terrell and LaStarza could not is partly a matter of physiology. He is made of different stuff and that stuff has reacted differently. Partly it is circumstantial; such is Povetkin’s promotional support in Russia that he was able to reintroduce himself immediately to good money – and to draw ranked fighters to the Moscow fortress that served him no advantage against Klitschko. But I wonder, too, if he is not driven by a certain sense of injustice. As I wrote in coverage for that fight, “if heart is the greatest attribute to which a fighter can lay claim, then Povetkin was a great opponent indeed, for in the eighth he showed as much as any heavyweight who has ever stepped into the ring.” Povetkin really tried against Klitschko and to a degree was let down by an incompetent referee. After the fight he made all the right noises, calling Wladimir the better fighter, but having reviewed the footage it must irk him that his heart-fuelled stab at the title was rendered chanceless by officiating. Perhaps the top of the mountain holds no fear for him, despite the agonies he suffered there, for this very reason.

Regardless, such was the margin of the defeat of Povetkin by Wladimir Klitschko that despite his ranking above some of the other top heavyweight contenders by virtue of his wider and deeper resume, he was not really in any discussion over who is to meet Wladimir Klitschko next. Even when he was restored to the #1 contender’s berth ahead of the likes of Tyson Fury, Deontay Wilder and Bryant Jennings, nobody expected Wladimir to drop everything and rematch Povetkin at the expense of the next generation; but Povetkin’s destruction of Perez in mere seconds has made him something new, even though that thing has yet to take on any real form. Ethereal in his identity, without a belt, or a route to the legitimate heavyweight king, Povetkin has become a bogeyman to the division and most especially to the two men jostling for a shot at Klitschko next. Do not expect to hear talk of either Tyson Fury or Deontay Wilder matching the #1 contender in an attempt to cement their own status as contenders. They will both neatly sidestep the man policing the world heavyweight title and wait for the call. The reason is a sound one: he would beat either one of them.

Povetkin will haunt Wilder and Fury now until they have had their title shots, or have been shorn of any belts. He will dog Wilder’s comeback. He will be made to lurk but will do so in the full glare of the #1 contender’s slot that has been made his until such time as he is beaten, something that only Wladimir Klitschko can do, but equally, something he has already done and something he is unlikely to do again any time soon. The champion has his own problems.

Made to look, for the first time, old, by Jennings, who in turn was made to look limited by Mike Perez, who in turn has been blasted out in mere seconds by a vastly superior Povetkin, Klitschko is poised at the far edge of an illustrious career. This combination has ushered in a game of thrones for the biggest seat in boxing. The heavyweight division is much maligned, but in my view the last few months have made it fascinating once more, a twisted web. In the middle of this web sits an ageing spider that has been preying upon all manner of intruders into his domain for an incredible eleven years – arranged around him are suitors positioning themselves in the belief that they are the right man to take advantage of his advancing years.

Should someone surprise us by doing so, or if Wladimir should reach the end of his ride, Povetkin’s haunting of the division will end with another title shot.

What price, King Povetkin?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoChris Eubank Jr Outlasts Conor Benn at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoJorge Garcia is the TSS Fighter of the Month for April

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

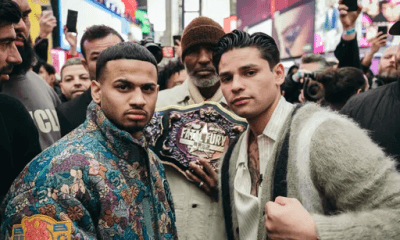

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRolly Romero Upsets Ryan Garcia in the Finale of a Times Square Tripleheader

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 324: Ryan Garcia Leads Three Days in May Battles

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoUndercard Results and Recaps from the Inoue-Cardenas Show in Las Vegas

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCanelo Alvarez Upends Dancing Machine William Scull in Saudi Arabia

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoBombs Away in Las Vegas where Inoue and Espinoza Scored Smashing Triumphs