Featured Articles

Tyson’s Bludgeoning of Biggs Another Example of Boxing’s Crueler Side

Compassion? Oh, sure, there is lots of it in boxing, if you know where to look. There is the memory of a concerned Floyd Patterson kneeling over the knocked-out Ingemar Johansson, Ingo’s left quivering uncontrollably, after the Swede had been felled by Floyd’s leaping left hook in the second of their three classic confrontations. There is WBC heavyweight champion Larry Holmes, in the process of stopping outclassed challenger Marvis Frazier in the very first round, signaling with his right hand to referee Mills Lane to step in and save Larry’s young friend from taking additional punishment.

“I met (Marvis) when he was a little-bitty kid,” Holmes, at the post fight press conference following the Nov. 25, 1983, bout in Las Vegas, said of the son of Joe Frazier, whom Holmes had long held in the highest esteem. “I was working with Joe as his sparring partner. That was one of the happiest moments of my life. I was like a kid in a candy store. It gave me a great thrill, even when Joe broke my ribs. We remained friends until the day they put him in the ground.”

But while the crucible of the ring has forged much mutual respect and more than a few lasting friendships, it also must be noted that animosity also can be the unforgiving residue of the hardest sport. Some fighters enjoy inflicting pain if they dislike their opponent or believe he has somehow done them wrong. Sometimes there doesn’t even have to be a reason for intentionally prolonging a beatdown; some great champions simply have a sadistic streak that served them well, in a professional sense.

Case in point: the Oct. 16, 1987, meeting of undisputed heavyweight champion Mike Tyson and 1984 Olympic super heavyweight gold medalist Tyrell Biggs in Atlantic City’s Boardwalk Hall. Tyson was seething even before the opening bell, and determined to do as much damage as was humanly possible to Biggs until the referee or ring doctor intervened.

“I was going to make him pay with his health for everything he said,” Tyson said of the revenge motive that prompted him to ease off whenever it appeared the battered Biggs was ready to go. “I could have knocked him out in the third round, but I wanted to do it very slowly. I wanted him to remember this for a long time.”

Biggs remembered, all right. Decked twice, he suffered two cuts that required 22 stitches to close – 19 above his left eye, three in his chin.

“I didn’t say anything that should have angered him,” Biggs said, incredulous that Tyson had made his destruction such a personal matter. “All I said was that I was confident I could beat him.

“There’s good guys and bad guys in wrestling, like Hulk Hogan and Ivan the Terrible. Well, I think Mike Tyson is the Ivan the Terrible of boxing.”

Truth be told, Tyson’s resentment of Biggs far predated anything that went on in the weeks preceding their actual meeting in the ring. They both were at the Olympic Trials in 1984, when Tyson was a callow teenager still in the process of refining his skills. Henry Tillman, who would not make it out of the first round against Tyson as a pro, instead was the United States’ heavyweight representative in Los Angeles.

In Tyson’s book, “Undisputed Truth,” he claims that Biggs belittled him at the Olympic Trials. When a woman approached Biggs to wish him and his newly certified teammates luck in the Olympics, and Biggs, nodding at Tyson, allegedly said, “He certainly ain’t getting on that plane.”

Any resentment Tyson may have harbored toward Biggs bubbled up after the fight was announced, with Biggs and chatty cornerman Lou Duva expressing their belief that Tyson was overrated and beatable.

“He’s never fought anyone like me,” Biggs said at the final prefight press conference. “I don’t know this Tyson, the way you guys (media) talk about him. I know Tyson from way back when. He’s strong, but his strength will not hurt me.”

It might have been typical bluster on the part of Biggs and Duva to hype the event, but Tyson was building up a rage inside himself that would be unleashed like a volcano on fight night.

“I want to hurt him bad,” he said of his plan for Biggs. And so he did.

“When I was hitting him with body punches, I heard him actually crying in there, making woman gestures,” a smirking Tyson said. “I knew that he was breaking down. I was very calm and I was thinking about Roberto Duran, how he used to cut down the runners and just wear them down. I had that frame of mind when I was in the ring. I wasn’t even thinking about (targeting Biggs’) cut. I was thinking about hitting him to the body – softening him up.”

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise that Tyson would reference Duran, whose mercilessness as he went about his work had made him Tyson’s hero and role model. What Tyson had tried to do to Biggs, and largely succeeded in achieving, was what Duran, the “Hands of Stone,” had done to a pretty good lightweight named Ray Lampkin when he sought to dethrone Duran, the WBA 135-pound titlist, on March 2, 1975, in Panama City, Panama.

As was the case with Biggs a dozen years later, Lampkin had made some seemingly innocuous remarks about how he thought Duran might be ready to be taken. And, as Tyson did against Biggs, the imperious Duran, who once said, “I’m not God, but something similar,” had used that as fuel for his fury.

“They were trying to make Duran out to be this Superman character,” Lampkin had said in the lead-up to the fight. “He’s human, and when you cut him he bleeds, just like I do. They’re acting like he can’t be beat, but I saw Esteban (DeJesus) do it.”

Unfortunately for Lampkin, he wasn’t Esteban DeJesus on a night that he needed to be more than he was. Duran, who also was a master of backing off when an opponent was on the verge of toppling, finally closed the deal in the 14th round. So damaged was Lampkin that he was unconscious for over an hour, and remained hospitalized for five days.

“I was not in my best condition,” Duran said in assessing his brutally effective performance. “Today I sent him to the hospital. Next time I’ll put him in the morgue.” It was a quote that forever defined Duran as a remorseless assailant. And while Lampkin recovered enough to resume his career, he was never the same.

“That was the fight that sent me downhill into retirement,” he said. “I never recuperated. I wanted to make myself believe that I did, but I kept getting hurt.”

Before he did what he did to Biggs, Tyson worked faster but just as devastatingly against Marvis Frazier on July 26, 1986, in Glen Falls, N.Y., four months prior to the 20-year-old Tyson winning his first heavyweight championship. The fight lasted just a half-minute, with Tyson going after Frazier like a ravenous wolf going after a slab of raw meat. But that was just the way he always fought, right? Well, maybe so, but there are those who believed then, and still do, that Tyson had more motivation than usual to make a statement against the son of the great Smokin’ Joe.

An unfailingly polite sort who is now a minister, Marvis didn’t really say anything that might have served to inflame Tyson. But Joe did, although his comments on how Marvis would handle Tyson was interpreted by some as how the elder Frazier thought he would do if only he could go back in time and be the one swapping haymakers with the young Iron Mike.

“I don’t see who (Tyson) really has beaten,” Joe said is dismissing Tyson as a false creation of the Cus D’Amato/Jimmy Jacobs hype machine. “You need to sit him down and teach him things instead of having him fight all the time against somebody who ain’t nobody. Putting him in the ring and having him knock out somebody who needs to be in the house cooking, it don’t make any sense. I don’t know how that’s going to make him champion.

“Marvis will be moving all the time. When he jumps in to fight, he’ll fight. He won’t be standing there holding hands and playing around.”

Beau Williford, who had trained Tyson victims James “Quick” Tillis and Lorenzo Boyd, understood how Tyson would react to Joe’s taunting. There would be hell to pay, and Marvis was the one who would do the paying.

“Tyson will eat him alive, spit him out and step on him,” Williford said of what Marvis could expect. “And if the old man keeps running his mouth, Mike will knock him out, too.”

A prime-on-prime matchup of Joe Frazier and Tyson, so similar in style and physical attributes, would be on any fight fan’s list of dream fights, if only wishing could make it so. But Smokin’ Joe did get it on three times with Muhammad Ali, who also gets a couple of nods as someone who could find the darker recesses within himself as the occasion warranted.

One such instance was Ali’s 12th-round stoppage of Floyd Patterson in Nov. 22, 1965, in Las Vegas, Ali’s second defense of his heavyweight championship and the first after he had scored that controversial first-round knockout of Sonny Liston in their rematch in Lewiston, Maine.

Ali, of course, had changed his name from Cassius Clay at that point, although Patterson was unwilling to identify him as such.

“I have been told Clay has every right to follow any religion he chooses, and I agree,” Patterson said. “But by the same token, I have the right to call the Black Muslims a menace to the United States and a menace to the Negro race … I do not believe God put us here to hate one another. Cassius Clay must be beaten and the Black Muslims’ scourge removed from boxing.”

Ali set out to not only defeat Patterson, but to humiliate him and to make him suffer for his temerity. Time and again Ali seemingly had Patterson teetering on the abyss, and time and again Ali backed off to allow the former champ time to recover and thus be pounded on some more.

By the 12th round, even Ali’s trainer, Angelo Dundee, had tired of the cat-and-mouse game. “Knock him out, for chrissake,” Dundee implored his fighter, who decided to do as requested. That 12th-round stoppage could have and probably would have come much earlier had Ali not been toying with Patterson, or had Floyd not been so obstinate in the face of certain defeat.

“It was hurting me to watch,” said referee Harry Krause, who wanted to step in numerous times but was hesitant to do so because Patterson was doing all he could to try to fight back. “Patterson was hopelessly outclassed. He lobbed his punches like a feeble old woman.”

Another Ali opponent, Ernie Terrell, would discover, as Patterson had, that there were consequences to referring to Ali as “Clay,” even if it was mostly unintentional.

Prior to their Feb. 6, 1967, bout in Houston’s Astrodome, Terrell, the WBA heavyweight champion, said the name that could set Ali off as nothing else could.

“I wasn’t trying to insult him,” Terrell is quoted as saying in “Muhammad Ali” His Life and Times,” by author Thomas Hauser. “He’d been Cassius Clay to me all the time before when I knew him. Then he told me, `My name’s Muhammad Ali.’ And I said fine, but by then he was going, `Why can’t you call me Muhammad Ali? You’re just an Uncle Tom.’

“Well, like I said, I didn’t mean no harm. But when I saw that calling him `Clay’ bugged him, I kept it going. To me it was just part of building up the promotion.”

But what’s good for the goose isn’t necessarily good for the gander. Although Ali would say his calling Joe Frazier a “gorilla” and “ignorant” was simply a means of building up the promotion of their fights, Frazier didn’t think that should have been the case. And neither did Ali when Terrell made the mistake of calling him Clay. From the eighth round on, Ali taunted Terrell, shouting time and again, “What’s my name?,” followed by bursts of blows to Terrell’s badly swollen eyes.

Tex Maule, writing in “Sports Illustrated,” concluded that Ali had engaged in “a wonderful demonstration of boxing skill and a barbarous display of cruelty.”

It is both elements – the compassion and sportsmanship, to be sure, but also the undeniable element of meanness – that go into the bubbling brew that makes boxing so compelling a reflection of the human condition. As Puerto Rican poet Martin Espada once noted, “Violence is terribly seductive; all of us, especially males, are trained to gaze upon violence until it becomes beautiful.”

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

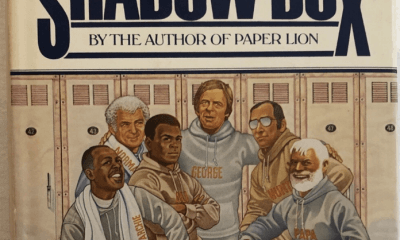

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates