Featured Articles

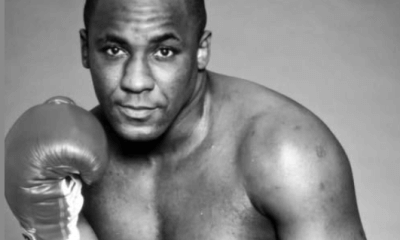

BACKUS IS ALWAYS `CANASTOTA’S OWN,’ BUT HE IS STILL WITHOUT A HALL PASS

The 27th annual International Boxing Hall of Fame induction class will be announced on Dec. 16, and again none of those to be enshrined next June will be named Billy Backus.

It is a curious case of inclusion and exclusion for a native of the picturesque central New York village of Canastota, where the IBHOF opened its doors in 1989 and welcomed its 53-member inaugural group of inductees in 1990, primarily because it is the hometown of the late, great Carmen Basilio and, to a lesser extent, his former world welterweight champion nephew, Backus.

But Basilio, who was 85 when he died on Nov. 7, 2012, is regarded as ring royalty everywhere, a tough-as-nails former welterweight and middleweight titlist who was a participant in THE RING magazine’s Fight of the Year five years running (1955 through ’59), a record that almost certainly never will be matched, much less broken. Whenever he returned to his hometown for the IBHOF induction ceremonies, Basilio, who had relocated to Rochester, N.Y., was the pugilistic equivalent of a rock star. The “Upstate Onion Farmer’s” annual appearances in Canastota were as much a cause for celebration as Elvis Presley coming back to his birthplace in Tupelo, Miss., to relive old times with the locals.

Backus, now 72, also is something of a prodigal son – since January 2006 the retired New York correctional department employee has lived in Pageland, S.C. – but his status on those occasions when he shows up in Canastota is not so much that of cherished civic treasure as of nice local boy who had his moment of glory in the ring, but not one so lasting as to assure him of immortality in the form of a plaque hanging on an IBHOF wall.

And while Backus isn’t really accepting of the situation, at least he’s come to grips with it.

“I usually come in on Wednesday (the day before the first events in the four days of official activities on Hall of Fame weekend) to see family and friends,” he said. “I come in early because I can, and before the rush (of fight fans) comes in. When the rush does come in, of course I don’t get to see my family as much. But I stay over to the next Wednesday, when I leave to go back to South Carolina.”

Backus – who almost always is introduced as a former world champion and, of course, as the nephew of Carmen Basilio – admits to being disappointed that he is not an inductee and, in fact, again wasn’t even on the ballot. There were 30 fighters on the list of “Modern” candidates (three newly eligible and 27 holdovers) for the electorate (full members of the Boxing Writers Association of America and a panel of international boxing historians) that determines which three will be part of the Class of 2016.

The IBHOF has drawn some flak in the past for having inducted fighters (Ingemar Johansson in 2002, Arturo Gatti in 2013 and Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini just this year are three that come to mind) who were well-known former world champions but, critics say, failed to attain the threshold of greatness that should be the standard for entry into any sport’s Hall of Fame. Those who believe the bar for joining the club should be set very high have argued that the voting process is flawed, especially in years when there are no cinch candidates to be considered, and that it has become something of a popularity contest in any case.

With a career record of 48-20-5 that includes 22 victories inside the distance, Backus is generally considered to be someone who falls into the category of the very good, but not indisputably great. But he figures his accomplishments are the equal of some who have been inducted, or at least those who made it onto the ballot, and it stings that he has been on the outside looking in on his June visits to a place that otherwise holds nothing but fond memories for him.

“I’ve questioned it in the past,” Backus said of his failed quest to be even be considered for induction. “I’ve given it up now. The guy in charge of the Hall of Fame, (executive director) Ed Brophy, was my neighbor in Canastota, right next door. In fact, I was the one who got him interested in boxing. From what I understand, talking to sports writers from all over, my name never even comes up. I asked Ed about it and he said, `Well, we have to put this guy up first, this other guy’s going to be eligible soon.’ They keep handing me a bunch of bull.

“But if that’s the way it’s going to be, I just have to let it go. I’ve given up on it. I probably should have been inducted five or 10 years ago. But now … if it happens, it happens. My oldest son – he’s 54 – told me, `When they do induct you, Dad, I’m not even going.’ He’s upset about it. But I don’t hold any grudges. It is what it is.”

With or without the Hall’s stamp of approval, however, nobody can ever take away or diminish Backus’ signal accomplishment, which is his stunning, fourth-round stoppage – as a 9-to-1 underdog – of intimidating welterweight champion Jose Napoles on Dec. 3, 1970, in War Memorial Auditorium in Syracuse, N.Y., just 20 miles or so from the house in which Backus grew up.

Forty-five years later, Backus said his upset of Napoles, a 1990 charter inductee into the IBHOF who was born in Cuba and based in Mexico City throughout much of his career, is the most indelible memory of his boxing career. The only thing that might have made it better is if he had actually been paid for that dream shot at the title.

“Napoles got $62,000, which was a lot of money at that time,” Backus recalled. “I got nothing. The five members of the Canastota Boxing Club had guaranteed Napoles so much to bring the fight to Syracuse, there was literally no money for me after Napoles got paid. Those guys had to take up a collection – remember, this was around Christmas – to put together $800 so I could buy presents for my kids.”

How Backus even got the title shot is a story unto itself. He was a pedestrian 8-7-3 after his first 18 bouts, more than a few of which he took on short notice and against fighters more experienced than himself. It seemed he was going nowhere fast, and when he lost an eight-round decision to Rudy Richardson on March 5, 1965, his third straight defeat – and, ironically, on Backus’ 22nd birthday – he decided to call it quits.

“I was working construction at the time,” Backus said. “I’d get a call from Tony (Graziano, his manager and first trainer) and he’d say, `I got you a fight on Friday night.’ I either had to leave work early or beg out entirely for that day. But I could pick up $50 or $60, and that was my motivation for staying in it – to get some extra money for my family. I wasn’t in it to get ahead in the boxing game.”

But then Backus got laid off from his construction job, which more or less forced him to devote himself more fully to boxing. And a funny thing happened. He began to win, slowly building up his own credibility to go with the distinction of being Carmen Basilio’s nephew. Name recognition doth have its privileges.

“If I performed really well, it was always noted that I was the nephew of the great Carmen Basilio,” Backus said. “But the more I looked at it, I realized it meant more publicity for me, more things for (the media) to write about. So eventually I was, like, `OK, I’ll go along with it.’

“Even Carmen laughed about it. He’d say, `I know, I know, they have to put it in there.’ He understood. I understood. What are you gonna do?’”

After Napoles stopped Pete Toro in nine rounds in a non-title bout in Madison Square Garden on Oct. 5, 1970, three possible candidates for the WBC/WBA champion’s next bout, an optional defense against someone in the top 10, and their representatives met in New York City to meet with Napoles’ management team. It was at that meeting that one of those fighters would be selected to challenge the champ.

“It was me, Eddie Perkins (whom Napoles had outpointed over 10 rounds on Aug. 3, 1965) and I can’t remember the name of the third guy,” Backus said. “I think he was from Hawaii or California, or maybe it was Michigan or Chicago.

“As far as records go, mine at that time wasn’t really that impressive (29-10-4, 15 KOs), even though I’d beaten some good fighters. Remember, I was working construction in the early part of my career so I was taking fights on short notice, when I wasn’t in great shape. I’d only be able to go hard for five or six rounds, then sort of glide through the last four. I lost a few decisions that way. Did Napoles (whose record then was 63-4, with 43 KOs) take me lightly? Oh, without a doubt.”

But for this fight, the most important of his career, Backus would have a not-so-secret weapon: his uncle Carmen.

“After I signed for the Napoles fight, Carmen came to me – he was working at LeMoyne College, as the physical ed director – and asked, `Do you need my help?’ I said, `Yeah, if you have the time,’” Backus recalled. “So it happened that we got to work together.

“Carmen had a lot of words to say, and I listened to them because I knew what he had gone through, what he had accomplished. He gave me the best way to get things done in the ring, to be the best that I could be.

“Now, as far as styles, his was a lot different than mine, even though we were both infighters. I stood back a little bit more and looked for the jab. Carmen always wanted to dig to the body and throw as many punches as he could. He made me more of a combination puncher. I think I hit with a little more power, but he threw punches in bunches. It makes a difference.”

If Napoles expected Backus to be a pushover, he learned soon enough that was not the case. And Backus just as quickly determined that Napoles, his pristine reputation notwithstanding, was a human being, not some indestructible god of the ring.

“Napoles was the Superman of the welterweights. He scared a lot of guys, but he didn’t scare me,” Backus said. “I’d been in the ring with my share of tough guys, and, of course, I’d studied films of him. He was a very good puncher, a sharp puncher. But how was he going to react when I punched him back?

“I gave him a couple of shots to the ribs and I heard him (groan). That’s all you need to hear when you hurt somebody a little bit. I don’t think he expected to get some real punishment back. He probably thought he was the superstar and I wasn’t supposed to be a threat to him.

“When you find out the other guy hits back hard enough to hurt you, then it’s a different program, and it’s not your program.”

After a terrific, back-and-forth third round, Backus, a southpaw, stung Napoles with a right hook. A bit later in the round, another right hook opened a laceration above Napoles’ left eye that was severe enough for referee Jack Milicich to step in and stop the bout.

Basilio went over to Napoles’ corner to have a look and was startled by what he saw. “He told me, `Wow! You can see the eyeball through the cut,’” Backus said.

“But I wasn’t looking to stop him on a cut,” Backus continued. “I wanted to knock him out with a right hook, like the one that caused the cut. I wanted to put him down and out.”

After winning two non-title bouts, against Bobby Williams and Robert Gallois, Backus’ first defense was a rematch against Napoles, on June 4, 1971, at the Forum in Inglewood, Calif. This time “Mantequilla” took back his title on an eighth-round technical knockout.

There would be more good nights for Backus, and some not so good. He got three more shots at the welterweight championship, losing twice to Hedgemon Lewis for the New York State Athletic Association version of the title and, in his final bout, by second-round stoppage to WBA ruler Pipino Cuevas on May 20, 1978.

Perhaps, had he had a few successes like his first meeting with Napoles, Backus would now be finding the closed door to the inner sanctum of the IBHOF at least somewhat ajar. But if he didn’t rise to the level of his uncle Carmen, at least he did enough to make the older man proud.

“Billy winning the world title is the best thing ever to happen in my life, even better than me winning the world title,” Carmen gushed after Backus had surprised Napoles.

It might not be as tangible a testimonial as his own plaque in the IBHOF would be, but for Billy Backus, earning his uncle’s seal of approval stands as an affirmation that is nearly as good.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoA Night of Mismatches Turns Topsy-Turvy at Mandalay Bay; Resendiz Shocks Plant

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering the Under-Appreciated “Body Snatcher” Mike McCallum, a Consummate Pro

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books