Featured Articles

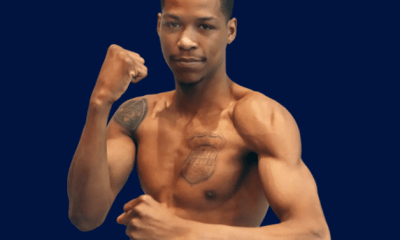

The Greatest Fighter Alive

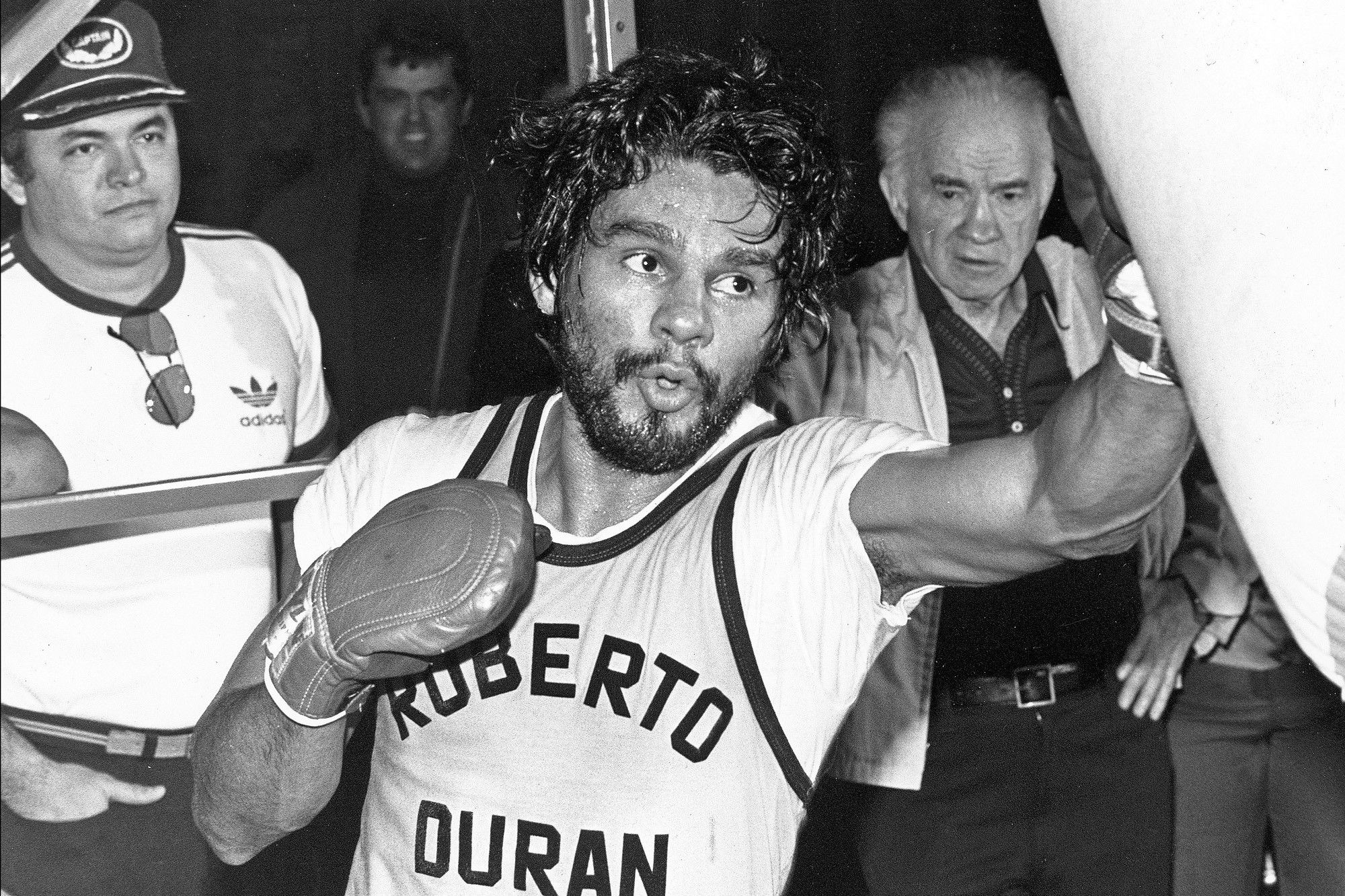

The Greatest Fighter Alive – Forty-four years after swiping Ken Buchanan’s world lightweight championship and thirty-six years after shoving Sugar Ray Leonard off a gringo pedestal to take the world welterweight championship, Roberto Durán is back in the limelight. “Hands of Stone” is something of a corrective to 30 for 30’s “No Mas” episode (2013) in that it recognizes Durán as something far more than Leonard’s straight man, though it only touches the barely-restrained savagery that had become his persona by 1980, a persona that Al Pacino admitted was the model for the Tony Montana character in “Scarface.”

Ray Arcel is played by Robert De Niro despite the fact that the rough-hewn actor more closely resembles Duran’s “other trainer” Freddie Brown. It was Brown, not Arcel, who was most responsible for streamlining Durán’s savagery but if you scan the screen looking for Brown’s trademark green sweater you’ll get no more than a glimpse. The movie also perpetuates a fable about Leonard’s first defeat that is as carelessly tossed around as Durán’s shaggy locks at street parties. I borrowed Ray Arcel’s comb and straightened things out for the record and with the record, but writer-director Jonathan Jakubowicz never got the memo.

Originally published on TSS as “The Fifth God of War,” what follows is closer to the truth than “The Hands of Stone” and carries a new title more to the point.

The Greatest Fighter Alive

A battered and bloodied world welterweight champion glowered at his corner men as the thirteenth round was about to begin. “If you stop this fight,” he said, “I’ll never talk to you the rest of my life.” In the opposite corner, a surging Henry Armstrong sprang out of his corner at the bell. Trainer Ray Arcel, a cotton swab in his mouth, watched the last three rounds with Barney Ross’s words echoing in his ears and a prayer on his lips. He prayed not that Ross would win, but that he would survive.

The vanquished champion was brought back to the hotel where Arcel put hot towels on his swollen face and tended to his wounds. He stayed with him four days and four nights.

That was 1938. Arcel had already been in the fight game two decades. He was at Stillman’s Gym from the beginning and taught hundreds of young men how to fight, including twenty world champions. His first was in 1923. His last was sixty years later.

Arcel met Freddie Brown at Stillman’s. Brown grew up on Forsythe Street in the Lower East Side not three miles from Benny Leonard’s house. He began training in the 1920s and had what A.J. Liebling described as the unmistakable appearance of old fighters: “small men with mashed noses and quick eyes” and a chewed-up stogie stuck on his lip that contrasted nicely with the clean cotton swab of Arcel.

Mangos

Twenty-year-old Roberto Durán’s American debut was at Madison Square Garden. Thirteen thousand, two hundred and eleven ticket-buyers watched him lay out Benny Huertas like a red carpet in less than a minute. Dave Anderson covered the fight for the New York Times. “Remember the name,” he advised.

Arcel was just sitting down when that stone fist crashed on Huertas’ temple. As the Panamanian left the ring on his way to the dressing room, he startled the old man again when he kissed him on the cheek. A month later Durán would be introduced to Brown and the triumvirate would be complete.

“When I came into his camp in 1972, he was just a slugger until I taught him finesse,” Brown said. A slugger? Durán was worse than that. He was a savage, a Roman wolf-child placed in a civilizing school where ancient masters taught the art of war. Agrippina summoned Seneca to tutor a young Nero. Durán’s manager summoned Arcel. Arcel brought in Brown. It took not one, but two eminent teachers to tame Durán, and Brown bore the brunt of it; camping outside his door to chase away the broads, dragging him out of bed at dawn for roadwork, locking up the pantry.

The two old men never did completely civilize their pupil, though they did better than Seneca. Nero, after all, used Christians as torches to light the streets of Rome. Durán listened, and because he listened, he lit up fighters in six weight classes.

In 1972, Durán indecently assaulted lightweight champion Ken Buchanan and snatched his crown. His reign of terror lasted six years and twelve title defenses.

“The only guy we had like him,” Brown told Pete Hamill, “is Henry Armstrong.” Brown and Arcel knew the combined value of explosiveness and intelligence in the ring. “Boxing is brain over brawn,” said Arcel whenever the subject came up. “If you can’t think, you’re just another bum in the park.” Durán was not only “one of the most vicious fighters we’ve ever had,” added Brown, “[he was] one of the smartest.”

Durán was destined to invade the welterweight division. When he did, it was as deep as it ever was. Waiting for him were shock punchers in Pipino Cuevas and Thomas Hearns, defensive specialist Wilfred Benitez, technician Carlos Palomino, and the smiling celebrity who lorded over them all —boxer-puncher Ray Leonard.

Malice

By the end of 1979, a clash between Leonard and Durán was almost certain. Durán had already retired Palomino in a dominant performance, while Leonard stopped Benitez and took the title. They fought separately on the Larry Holmes-Earnie Shavers undercard and Leonard’s trainer Angelo Dundee watched the Durán bout very carefully. “Durán is thought of as a rough guy, but he’s not rough,” he observed. “He’s smart and slick.”

Arcel, eighty-one, and Brown, seventy-three, were watching Leonard as well, though they were very familiar with his style and how to beat it. They had already trained about thirty world champions between them. Fifty-eight-year-old Dundee had trained nine. In fact, Dundee’s novitiate was at Stillman’s Gym where he handed towels to the two masters he now matched wits with.

The posturing began soon enough. At Gleason’s Gym, Leonard was watching Durán skip rope when Durán spotted him and began lashing the rope with uncanny speed, while squatting. At a press conference at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City, Durán cuffed Leonard, claiming that Leonard put his hand near his face. Two days before the fight, both men were at an indoor mall in Montreal, and Durán learned just enough English to yell, “Two more days! Two more days!” Leonard blew a kiss, and Durán charged at him and had to be restrained.

Durán was getting mean, but it was Leonard who had every physical advantage. He was younger, faster, taller, and bigger. “I’m not Ali,” Leonard insisted to the pundits. “Sure, maybe at the start I was trying to do his shuffle or his rope-a-dope, but not now.”

Durán looked pudgy in his last two outings, and the previous three welterweights he faced went the full ten rounds. Never before had three in a row gone the distance with him, and there was chatter about his motivation. Durán himself admitted that he was not always committed to training and his trainers did too, though a warning was attached: “When you’re fighting smear cases and you’re the best fighter around, it’s hard to be interested, but now he’s inspired, and when he’s inspired, he’s relentless,” Arcel said. “Leonard can’t beat this guy.”

The odds makers disagreed. Durán was a nine-to-five underdog.

Leonard was confident enough to ask permission from an aging Ray Robinson to borrow “Sugar,” but he couldn’t have anticipated how many lumps he’d get from Durán, who had more in common with fighters from Robinson’s era than he ever would.

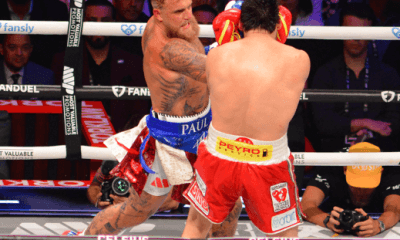

As Leonard made his way toward the ring on June 20, 1980 Roberto Durán shadow boxed his own demons in the red corner. Both were in the best condition of their lives, though Durán exuded something like preternatural malevolence.

Arcel had already promised that we would witness “the darndest fight” we ever saw. And we did.

Durán had promised to use “old tricks” against Leonard. Old tricks. Freddie Brown’s fingerprints were all over the place. He trained him at Grossinger’s Resort in the Catskills, where he worked with Rocky Marciano in the 1950s and Joey Archer in the 1960s. Brown had more tricks than a cathouse. Durán could be seen holding Leonard in the crook of his arms to stop incoming shots and create the perception that Leonard was doing nothing. Then there was the “Fitzsimmons shift.” Dundee himself saw it: “. . . if [Durán] missed you with an overhand right,” he observed, “he’d turn southpaw and come back with a left hook to the body.” Durán executed it against Leonard in the fifth, seventh, and eighth rounds. Bob Fitzsimmons invented it and used it to implode Gentleman Jim Corbett in 1897. It’s a peach of a move.

The Hands of Stone controlled the action in this career-defining bout. His savvy was no less a deciding factor than his savagery but make no mistake, Sugar Ray pushed him almost beyond his limits.

There were over forty-six thousand witnesses. Every now and then, one of them, a thin and solitary Nicaraguan with a mustache could be seen standing up from his seat and waving a little Panamanian flag. It was Alexis Arguello.

Myths

Durán’s strategy was drilled into him. He was instructed to be elusive against the jab, close the distance, crowd Leonard, and hammer the body.

Leonard’s aggressive strategy made things more—not less—difficult to cope with for precisely the reason that Dundee had alluded to: good little guys don’t beat good big guys. “In this fight, Durán’s not the puncher,” he said. “My guy is.” The respective knockout percentages over their previous five fights confirm this: Durán’s was forty percent, Leonard’s one hundred.

Leonard promised to stand and fight more than expected. “They all think I’m going to run. I’m not,” he said to New York Magazine. “I’m not changing my style at all . . . he’ll be beaten to the punch . . . those are the facts,” he continued. “What’s going to beat Roberto Durán is Sugar Ray Leonard.”

Dundee substantiated this in his autobiography. His strategy became certain from the moment that he watched the films and deconstructed Durán’s style. Dundee said that Durán was a “heel-to-toe guy. He takes two steps to get to you. So the idea was not to give him those two steps, not to move too far away because the more distance you gave him, the more effective he was. What you can’t do in the face of Durán’s aggression was run from it, because then he picks up momentum. My guy wasn’t going to run from him.”

So there you have it.

Leonard’s strategy in Montreal was deliberate and sound. After it failed, Dundee and Leonard revised history and a willing press has gone along with it ever since. We’ve been spoon-fed a fable that has long-since crystallized into orthodox boxing lore. It is the archetypal image of the Latin bully who “tricked” our all-American hero into an alley fight, and it sprang from the idea that Leonard “did not fight his fight” because Durán challenged his masculinity.

The problem is that the idea is at complete odds with Leonard and Dundee’s statements about Leonard’s clear physical advantages and the strategy that would be formed around those advantages. It contradicts Dundee’s earlier statements about Durán’s high level of skill, and it contradicts statements both had made immediately after the bout before they had time to think about posterity: “You’ve got to give credit to Durán,” Dundee told journalists. “He makes you fight his fight.” When asked why he fought Durán’s fight, Leonard said he had “no alternative.”

Since then, Leonard’s loss to Durán has been cleverly spun, re-packaged, and sold at a reduced price. It’s time to find our receipt and exchange a fable for the facts. And the facts begin with this: when both fighters were at their best, Durán was better.

Memento Mori

Durán’s record stood at 72-1 with fifty-six knockouts. As he simmered down in the aftermath of the fight, the magnitude of it all set in. He knew that Leonard was great. At the post-fight press conference, he was asked if Leonard was the toughest opponent he ever faced. Durán, his face scuffed and swollen, thought for a moment. “Si,” he said, “. . . si.”

And then something changed. Whatever it was that raged inside Roberto Durán —a legion of devils, his hatred of Leonard, the memory of a child begging on the streets of Chorrillo— faded from that moment. He became more sedate. After thirteen years of pasión violenta and after a victory that is almost without equal in the annals of boxing history, he fell like all who forget that they are mortal, and his humiliation would be so complete that it would obscure everything else.

Old embers would flare up only sporadically after the fateful year of 1980. Three times more he would remind the world of his greatness against men that no natural lightweight in his right mind would challenge. By then the two old men had walked away. Arcel and Brown joined us in the audience and watched a melting legend fight youngsters. As the curtain slowly descended on a career that would span five decades, there was little left that recalled what he was; just some old tricks in an arsenal ransacked by age and an unbecoming appetite.

But what he was should not be eclipsed. It should be remembered. When the splendor that was Sugar Ray Leonard entranced America, Brown and Arcel closed the blinds and applied old school methods in the shadow of Stillman’s Gym. They brought a Panamanian to a peak of human performance so perfect in its blend of science and ferocity that it would never be approached again — by Durán or anyone else.

After the final bell, a jubilant Durán leaps into the air. Before he lands he sees Leonard daring to raise his arms in victory and his eyes burn. He shoves and spits at his adversary, then stalks toward the ropes at ringside and grabs his crotch as he hurls Spanish epithets. Arcel tries to calm him down. The announcer shouts “le nouveau!” into the microphone, and victorious, the raging champion is hoisted up above the crowd —above the world— still cursing the vanquished.

This is Durán.

|

|---|

______________________

Springs Toledo is the author of In the Cheap Seats (Tora, 2016) and The Gods of War (Tora, 2014).

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

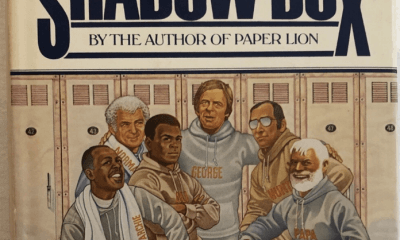

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates