Canada and USA

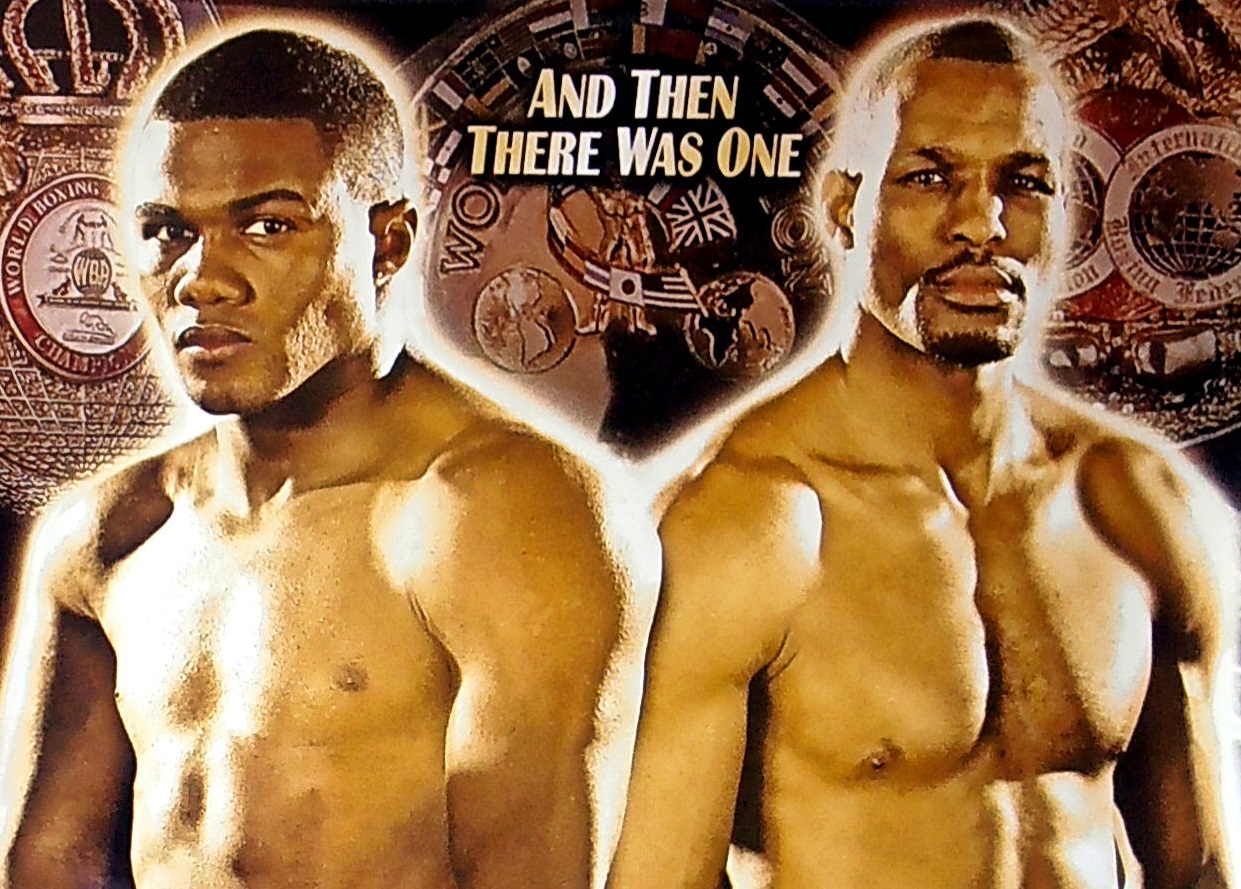

15 Years Ago Today: Hopkins Thrashes Trinidad; The Apex of B-Hop’s Amazing Career

By BERNARD FERNANDEZ

Revenge is a dish best served cold.—Unknown

There are great artists whose work is routinely excellent, but even they are apt to say there was one shining moment when they were at the absolute peak of their powers, when they found a way to reach deep inside themselves and achieve perfection, or as close to it as any living, breathing human being ever comes.

Bernard Hopkins turns 52 on Jan. 15 of next year and boxing’s ageless wonder continues to pine for one final fight that might further demonstrate that his amalgamation of skill, focus and longevity are unmatched in the annals of the ring. But even if B-Hop were to procure such a bout, and school still another high-level opponent young enough to be his son, it would not – could not – be considered the apex of a career that is sure to eventually gain him first-ballot induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

No, that ascent to the loftiest peak his sport has to offer will for Hopkins forever remain the night of Sept. 29, 2001, when the then-36-year-old, as a 3½-1 underdog, systematically dismantled 28-year-old Felix “Tito” Trinidad en route to a 12th-round technical-knockout victory in Madison Square Garden. The supposed upset in the final of a four-man middleweight unification tournament made Hopkins the consensus Fighter of the Year and, finally, gained him recognition as a megastar after he had labored for years in the shadow of other elite boxers who were, at best, on something akin to his level but probably a cut below.

“I don’t know if I can label him as a superstar or not. Only the fans can grant that status, and it isn’t solely determined by how well someone fights or how much talent he has,” Kery Davis, then the senior vice president of HBO Sports, said after Hopkins had shocked the world, if not himself, with his virtually flawless performance. “But from a strictly boxing standpoint, Bernard Hopkins has legitimized himself as one of the greatest middleweights of all time. He clearly is the best middleweight in the world, and no one can dispute that. All roads in the division lead through Bernard right now.”

But on this, the 15th anniversary of Hopkins-Trinidad, what happened inside the ropes before a desperate, pro-Trinidad crowd of 19,075 and a TVKO Pay-Per-View audience tells only part of the story. Amazingly, the run-up to the bout – delayed two weeks from its originally scheduled date of Sept. 15 by the deadly terrorist attacks on New York City’s World Trade Center on 9/11 – was just as compelling, if not more so, than anything two men wearing padded gloves could generate. Other prefight developments came in the form of two incidents in which a defiant yet coolly calculating Hopkins threw the Puerto Rican flag to the ground at press conferences, enraging Trinidad and his followers; the apparent bias shown by Don King, who promoted all four fighters in the tournament, toward Trinidad, and a hand-wrap controversy that ultimately would cast at least the appearance of a shadow on “Tito’s” otherwise sun-bathed legacy.

“I had come in from my morning run in Central Park when I turned on the TV and saw the coverage of the first crash,” Hopkins, a few days before the rescheduled fight took place, recalled of the horrifying sight of the first of the WTC’s twin towers ablaze after being struck by a hijacked airliner. “I thought it might have been an accident, a really terrible accident, but then I saw the second plane come in and hit the second tower.

“My first reaction was that this was no accident, it was a terrorist act. You see something like that, you’re not thinking about boxing. Trinidad was the furthest thing from my mind just then. What I was thinking about was getting the hell out of town. I ain’t no crying guy. Where I came up (on the mean streets of the “Badlands” in North Philadelphia), crying was, like, a sign of a punk. But I got teary-eyed then. I thought about the people in those buildings who were dead (the final body count was 2,996) or hurt. I thought about maybe never seeing my wife or my daughter again. For all I know, another plane might be on the way to hit my hotel. Someone might have planted a nuclear bomb in the city. I mean, you just don’t know.”

It would not have surprised anyone had the powers-that-be ordered at least a temporary shutdown of everything that constituted regular life in a stricken and grieving city. But, well, the NFL staged games only two days after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963 (a decision then-NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle always regretted), and the feeling was that America needed to show the perpetrators of this most heinous of acts that its citizens were strong enough and resilient enough to press on despite having endured unspeakable tragedy. After some debate, the decision was to delay the fight a mere two weeks instead of cancelling it outright.

For his part, Hopkins had enough room in his heavy heart to readily recommit to the task at hand. Asked if his animosity toward Trinidad was genuine or merely a ploy to get inside the Puerto Rican slugger’s head, B-Hop suggested that maybe it was a little bit of both.

“People think I hate Trinidad,” he said of the figurative villain’s cloak he had no hesitation in wearing, at least as far as Puerto Rico’s 3.8 million residents were concerned. “I don’t hate Trinidad. I don’t like Trinidad. There’s a difference. I hate this (Osama) bin Laden guy. I hate the guys who killed Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy.”

Part of the emotional fire that has always roared inside Hopkins is his belief that he has always been somehow disrespected, disregarded and relegated to a lesser seat at the table of premier fighters. Even though his unification bout with Trinidad (who, in just his second bout as a full-fledged middleweight, went in as the WBA champion while Hopkins held the IBF and WBC titles) would be, if successful, his 13th defense, one shy of the record held by the legendary Argentine, Carlos Monzon, the ex-con and reformed street tough from Philly remembered every perceived slight as if it were a freshly delivered slap to his face. Hadn’t he had to make a couple of those defenses on someone else’s undercard? Sometimes in off-the-beaten-track burgs like Shreveport, La., Upper Marlboro, Md., and Indio, Calif.? And how about the time he was obliged to accept a paltry $100,000 payday as a defending world champion?

Hopkins’ mindset thus was that of the perpetual underdog, forever having to prove himself to the doubters who were reluctant to acknowledge his greatness. He had a particular disdain for Olympic gold medalists, believing that they entered the pro ranks with silver spoons in their mouths and paths to the top cleared of most of the obstacles he’d had to overcome. Trinidad, although not an Olympian, had won world titles at welterweight and super welterweight while forging not only an undefeated record (40-0, with 33 knockouts), but a reputation as a devastating puncher, especially with the left hook.

After Trinidad had dethroned WBA middleweight champion William Joppy on a fifth-round stoppage on May 12, 2001, in the first semifinal of the unification tournament, Joppy, who had previously derided the Puerto Rican as “a little overrated” and “someone who doesn’t belong in the same ring with me,” was singing a different tune.

“I never thought he would be able to hit like that,” said Joppy, who was floored in the first, fourth and fifth rounds. “I didn’t think he’d have that much power, moving up from 154 pounds to 160. I have never been hit like that before.”

Said Al Mitchell, whose fighter, 1996 Olympic gold medalist David Reid, had been dropped four times in losing a one-sided unanimous decision and his WBA super welterweight title to Trinidad on March 3, 2000: “(Trinidad) reminds me of Joe Frazier. His offense is his defense. Trinidad bends, but he doesn’t break. He’s always putting pressure on you.”

But Hopkins, taking note of the fact that Trinidad had been knocked down seven times in the past, wasn’t buying into the prevailing notion of Tito’s invincibility. He saw weaknesses he believed he could exploit, weaknesses that would be even more apparent on fight night if he could play the kind of mind games at which he was so adept and would serve to throw Trinidad off his game.

“Trinidad hasn’t had to go to a Plan B his entire career,” Hopkins proclaimed. “But when it’s time to get down in the trenches, he’ll do what he always does, which is to charge in and throw bombs – and that’s when he’ll play right into my hands. Trinidad can’t cope with all the things I’m going to show him. He won’t be able to settle into a comfort zone. I’m going to show him a little Gypsy Joe Harris, a little Jersey Joe Walcott, a little Bennie Briscoe. He’s going to see more than he’s ever seen in 12 rounds, if it goes 12 rounds.”

As part of his preparations, Hopkins formulated Operation Piss-Tito-Off, which began on the first leg of a four-day, three-city promotional tour in July, when B-Hop snatched a Puerto Rican flag out of his opponent’s hands and flung it to the ground in New York City. Amazingly, or maybe not, he did the same thing two days later in San Juan, P.R., nearly inciting a riot and obliging him and his support team to literally flee for their lives. But a seed had been planted that later would bear fruit.

The act of an out-of-control madman or brilliant tactics?

“I think before I do something,” Hopkins said after the first flag toss, adding that he would (throw the Puerto Rican flag to the ground again), if I had to.”

Trinidad, who had calmly reacted to a certain amount of yapping from such previous foes as Joppy, Pernell Whitaker, Hector Camacho and Fernando Vargas, professed to be unaffected by Hopkins’ antics. “I don’t care what he says,” Trinidad insisted. “He can talk all he wants, as far as I’m concerned. It won’t make any difference once the bout begins.”

Still, Trinidad seemed legitimately shaken by Hopkins’ first snatching of the Puerto Rican flag from his hands, and downright dumbfounded when he did it again in San Juan. This went beyond the standard trash-talk that many fighters engage in.

“Every punch I give Bernard Hopkins will be like punching the bell of liberty,” Trinidad said during the Philadelphia stop, where homeboy B-Hop also met with some degree of hostility from those attending: “Puerto Rico must be respected.”

Hopkins, who feeds as much off negative reaction from the crowd as from positive energy, figured his strategy was working even better than he had intended. Now, he reasoned, Trinidad had no alternative but to come after him with everything he had, to uphold the honor of his island, a heaping plate of revenge Tito would attempt to serve hot, not with cold detachment.

“I can’t beat 12,000 people all at once,” Hopkins said of his estimate of the number of Puerto Rican fans or sympathizers who would be lustily backing Trinidad at the Garden. “But I can take something they love and hit them with the equivalent of a right hand to the stomach, and that was the thing with the flag. I got mine in first.”

Moreover, Hopkins added, “I saw fear in Antwun Echols’ eyes (when they fought). I saw fear in Robert Allen’s eyes, in Keith Holmes’ eyes. And I saw it when I took the flag out of Trinidad’s hands in New York. People used to be petrified when I was young and they saw me on the street. I’m not proud of that. But that’s what I saw in Trinidad’s eyes. Maybe for the first time ever, he’s not sure that he can win.”

Nor was Trinidad the only object of Hopkins’ discontent. It irked him that King, at every press stop, would wave a tiny Puerto Rican flag and cackle “Viva, Puerto Rico!” To B-Hop’s way of thinking, his Hairness couldn’t have made his preference as to the fight’s outcome more obvious.

“Don King has an agenda,” Hopkins said prior to the terrorist attacks on the WTC. “I understand that. Bu there’s a price to be paid for having that agenda. On Sept. 16, the day after I beat Trinidad, King is going to be knocking on my door, sending me flowers and candy, trying to make nice. And that’s when he’ll find out I have an agenda, too. I don’t like it when my own promoter doesn’t treat me with the same respect he’s showing the other guy. I’m not asking for favoritism; I’m demanding equality.”

Those hijacked airliners crashed into the twin towers and everything connected to the fight, understandably, was put on hold. Additional security measures were instituted, mostly because of lingering fear of another terrorist attack but also because Garden officials, aware of Hopkins’ incendiary mistreatment of the Puerto Rican flag, worried about a replay of the riot that erupted following foul-prone Andrew Golota’s disqualification loss to Riddick Bowe on July 11, 1996. In any case, Hopkins’ grand scheme was brought back into sharp focus when he learned that the Sugar Ray Robinson Award, which was to be presented to the winner of the unification tournament, had already been pre-inscribed with Trinidad’s name on it.

Another sidelight to what already was shaping up as a fight perhaps unlike any other occurred when Hopkins’ assistant trainer, Brother Naazim Richardson, observed what he said was the improper taping of Trinidad’s hands, which he said was not in accordance with New York State Athletic Commission rules and might have added to his already vaunted punching power. Richardson said Trinidad’s wraps were “layered” — tape, gauze, tape, gauze, etc. — with tape directly over the knuckles. The rules stipulate tap cannot be applied directly over the knuckles and that the required 10 yards of gauze and two yards of tape must be applied in “one winding,” without layering. The NYSAC observer agreed, and he ordered Trinidad’s hands to be taped to specifications.

“If you put on tape, then gauze, then tape, then gauze, it’s like a (plaster) cast,” Hopkins would say later. “It’s like being hit with a baseball bat. I’m giving out some secrets here, but you can dip your hands in ice water and that tape will, like, marinate and become harder. But it’s only cheating if you get caught. Personally, I think Vargas’ and Reid’s people dropped the ball. Naazim did a brilliant job in spotting what (Felix Trinidad Sr., his son’s trainer) was doing with the wraps.”

All that remained was for the fight to begin, and it wasn’t long before it became apparent to everyone that Hopkins couldn’t have written a script that would have played out any better than what actually took place. After a mostly uneventful, feel-out first round that ended with Trinidad returning to his corner and mistakenly telling his pop that “(Hopkins has) got nothing. He’s mine,” the Philadelphian put on a clinic in the administration of purposeful and precise punishment. Hopkins wobbled Trinidad with a right uppercut in round 10 and, in the 12th, he whiffed on a left hook but came back with a right hand over the top that caused the badly battered Tito to crash to the canvas as if he had been pole-axed. Thinking he had won by knockout, B-Hop fell onto his back in celebration. But referee Steve Smoger ruled that Trinidad had risen at the count of nine, and he was prepared to wave the fighters together again when Felix Sr. entered the ring and threw in the towel. The end officially came after an elapsed time of 1 minute, 18 seconds.

When the end came, Hopkins led on the official scorecards by margins of 109-100 (once) and 107-102 (twice).

“To be great, you have to do great things,” said Hopkins, who was paid a then-personal-best $2.2 million and who reportedly bet $100,000 on himself. “You can’t just talk great. You got to fight your way through it.

“I knew I was headed for destiny. I was prepared to show that I am what I always said I am: the best middleweight in the world. My actions speak louder than my words. People are judged by their performance. They should be. Judge me by what you saw.”

Trinidad, who did not attend the post-fight press conference, grudgingly allowed in the ring that “Hopkins is a great champion. He is better than I thought.”

Perhaps, had there been a rematch, Trinidad might have reversed the outcome, as Sugar Ray Leonard had done in a do-over after he had been outpointed in the first of his three meetings with Roberto Duran. Then again, probably not, as the arc of both men’s careers provided ample evidence that Hopkins was simply a better fighter, and probably would be again if he and Trinidad had crossed paths a second time. But circumstances dictated that such a meeting would never take place.

After he knocked out Oscar De La Hoya in nine rounds on Sept. 18, 2004, to add “The Golden Boy’s” WBO middleweight belt to his collection of 160-pound straps, Hopkins, by then no longer part of the Don King stable, said King would almost certainly insist on options on B-Hop as a prerequisite for making Hopkins-Trinidad II.

“If it’s Trinidad, do I have to give Don King options on me?” asked Hopkins, who said such an arrangement was not acceptable to him, and never would be. “I’d fight Trinidad, but only if it’s a one-and-done.

“To me, Trinidad was the easiest fight of the last eight or nine that I had. I’m not saying that to be bragging. Look at the tape. Trinidad will never beat Bernard Hopkins because styles make fights and he’s one-dimensional. I’d just beat him up and knock him out. But people would want to see it, though.”

That assertion by Hopkins never seemed more accurate than in the aftermath of Trinidad’s embarrassingly wide unanimous-decision loss to Winky Wright on May 14, 2005. In the next-to-last bout of Trinidad’s career, Wright won all 12 rounds on one judge’s card, and 11 of 12 on those submitted by the other two judges. Tito followed that defeat with another near-shutout points setback to Roy Jones Jr. on Jan. 19, 2008, before deciding to hang up his gloves.

Noting that he had registered a unanimous-decision victory over Wright (on July 21, 2007) and Jones (on April 3, 2010), Hopkins said that the question as to who is the better fighter, he or Trinidad, should forever have been put to rest.

“I softened up Trinidad real good for Winky or anybody else that can box a little bit,” Hopkins said after Wright’s romp past Tito. “I opened the floodgates. It’s like when guys started standing up to Mike Tyson. The intimidation factor was gone. Same thing here. Nobody’s scared of Trinidad now.”

Trinidad was inducted into the IBHOF in 2014, his first year of eligibility, and deservedly so. But boxing is like life in many respects, one of which is that there probably is someone better than you at a given point in time, and some who are worse as well. Arrogance and humility live side by side in the crucible that is the ring, one or the other always ready to intrude upon one’s expectations and sensibilities.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds