Argentina

Malfunctioning Radar: The Tragic Fate of Wilfred Benitez

WILFRED BENITEZ, BOXING’S BOY WONDER — They said he possessed radar. The military uses radar to detect enemy aircraft and guided missiles. Air traffic controllers and pilots rely on radar during heavy fog and darkness to keep 300,000-ton 747s from landing anywhere other than the runway. Traffic court judges say it’s infallible. Wilfred Benitez used his radar to slip the punches of some of the best fighters in history even while pinned against the ropes or trapped in any of the four 90-degree angles of the ring. Many of those who witnessed this ring marvel in the flesh say he was the greatest defensive fighter ever.

The same experts who witnessed from up-close the graceful sidesteps of a feinting-and-ducking Willie Pep, or the cobra-like reflexes of a young Muhammad Ali, or the silky-smooth slickness of boxers like Jose Napoles, Billy Graham, Willie Pastrano, and Georgie Benton, use words to describe Benitez that they didn’t use for anyone else. Some of those experts, like Ray Arcel, went as far back as Benny Leonard in the 1920s and as far south as Buenos Aires, where Nicolino “The Untouchable” Locche thrilled sold out crowds with maneuvers that included cupping each knee with his gloved hands and making his opponents miss despite standing directly in front of them. None of those fighters were described as having radar. And no other boxer was said to possess another quality attributed to Benitez – the ability to anticipate punches that weren’t yet thrown.

That he went on to become a defensive wizard is even more amazing considering Benitez started out as a stalking, power puncher. Born in the Morrisania section of the Bronx, Benitez was the last of eight children born to Gregorio and Clara Benitez. Before he turned eight, a typical summer weekend saw Benitez and his three brothers follow their father to the school yard of P.S. 124 on E 160th Street and Tinton Avenue carrying a pair of boxing gloves and a stick of chalk. Near the handball courts in the back, one of them would draw a square on the ground with the chalk large enough for them to box. Through the chain link fence, Gregorio challenged any boy who passed by to get in the “ring” and fight one of his boys. With some coaxing, and the promise of a piece of the “live gate,” Gregorio had a bunch of kids in their street clothes eagerly swapping wild punches in a place where – on normal days – children played hopscotch or threw a Spalding ball. Benitez, who boxed without a protective headgear strapped over his little Afro, often fought twice on those days, sometimes against boys as old as 13. At the end of those afternoons, he would receive one dollar and a couple of lumps and bruises. That dollar was twice the amount Gregorio said he ever made when, as a youth, he “sparred” in the streets of Puerto Rico.

Gregorio was born on May 24, 1928 in Puerto Rico. Looking for better opportunities than those he found in the suppressed Puerto Rico of the 1940s, he left for the Bronx just months before the passing of Law 53. That law, also known as the Gag Order, made it illegal to write, or talk, negatively about the local government. The law also outlawed the Puerto Rican flag and anyone caught displaying or waving the five red-and-white stripes would end up behind bars. Less than three years after Gregorio left, a series of revolts erupted throughout the island and lasted until U.S. military bombers blanketed the citizens of Jayuya and Utuado with bombs and bullets while foot soldiers tossed grenades into backyards and living rooms.

Gregorio left just before Puerto Rico turned into a battlefield and settled into a routine of fixing brakes and tuning carburetors by day, and visiting boxing gyms by night. Gregorio, who wore his hair straightened like the singer James Brown, was a regular at gyms where Sugar Ray Robinson and Kid Gavilan trained. Though he never competed in organized matches, he had “boxed” for nickels and dimes on dirt fields as a child and sparred countless rounds in gyms. In the 1940s, when Puerto Rico was effectively turned into an island of sugar mills, boxing went through a lull. The sport had been legalized there in 1927 and less than ten years later, locals Pete Martin, Pedro Montanez and Sixto Escobar had become international stars while several others had risen to coveted spots in the top ten.

The first to break the ranks was Nero Chen, a fighter of whom little is known today except that he was dark complexioned and had epicanthic folds above his eyes. Because of that, he was called El Negro Chino, and later, Negro Chink, Nero Chink and, finally, Nero Chen. Another early contender was Escolastico Sotero Fortier, who gained famed as “Koli Kolo” – a childhood nickname derived from the mispronunciation of his first name. By the time Montanez and Escobar retired, the most notable Puerto Rican boxers, Cocoa Kid and Jose Basora, were campaigning off the island and were often billed as Cubans or “negroes.”

Gregorio was familiar with each of those boxers and later, when living in the Bronx, he would closely study from afar the ascensions of Emile Griffith, Carlos Ortiz, Jose Torres, and Frankie Narvaez. When his sons were old enough to dress themselves – except the youngest, Wilfred, who hadn’t yet learned to master making loops out of his shoe laces – Papa Gregorio decided that they would each become boxers and that he would train them.

He taught them to throw left hooks like Sugar Ray Robinson did and had them bruising rib cages with the same zest that Marcel Cerdan used to. The lessons learned during those school yard brawls by the handball court were absorbed more readily than any from inside any of the classrooms they attended inside of the three-story brick building that cast a shadow a few feet away from their cement boxing ring. Those school yard boxing sessions, however, ended abruptly.

1960s America saw many major cities in decay. The federally funded highway projects that began after World War II made the suburbs more attractive for middle class families, who loaded the backs and tops of their station wagons with their belongings and headed for the calm of the no-longer-hard-to-reach areas just outside of the big cities. In 1964, a series of riots broke out throughout the inner cities, the boiling point coming after a white superintendent in New York’s Upper Eastside decided to “wash away” the teens gathered on the front stoop with his garden hose. The drenched youths fought back, protests and unrest followed and when it all ended, a 15-year-old was dead from one of the three rounds an off-duty cop unloaded into his torso. With racial tensions boiling, crime rising, and drug use rampant, Gregorio, looking for better opportunities than those he found in the suppressed Bronx of the 1960s, packed his suitcases and left for Puerto Rico.

Behind their home in Puerto Rico, where the driveway came to an end, in a spot a swimming pool would have fit nicely, Gregorio had a boxing ring built. Along the sides, a few punching bags were hung. One of the bags, held together by duct tape, still hangs today though the gym’s roof was blown off by a hurricane. When the gym first opened, the recent successes of Carlos Ortiz and Jose Torres had the popularity of boxing on the island at the same levels they were in the 1930s when Montanez and Escobar were beating up future Hall of Famers. It wasn’t long before kids on the other side of the Trujillo Alto Expressway joined Gregorio’s four sons at the gym.

Alfredo Escalera, Esteban DeJesus, and Carlos DeLeon were soon training under Gregorio. The sparring sessions between Benitez and DeJesus, who was born in 1951, were especially violent. DeJesus’s power was described by one Puerto Rican trainer as beastly and he said that though Benitez gave as good as he took during those sessions, there were days when what he took was severe. Rather than put a stop to those sessions, Gregorio told his son the more he got hit, the more he needed to spar. In backyard sparring sessions that many felt should never have taken place, Benitez developed his radar.

Exactly how old was Wilfred Benitez when Gregorio moved the family to Puerto Rico?

When Lou Duva of Garden Promotions sponsored the National AAU tournament between the US amateur team and the Puerto Rican national team at the Paterson Armory just before Christmas 1972, the bantamweight was reported as “16-year-old sensation, Wilfredo Benitez.” When he boxed for the first time as a professional in New York in 1974, his reported age was 18. That would’ve made him 19 or 20, depending on his birth month, when he became champion after defeating Antonio Cervantes in 1976.

The story goes that the “Wilfred-o” Benitez who was billed as 16 in 1972 and 18 in 1974 really was Wilfred – without the “O” – and that he was born on September 12, 1958. Never mind that Gregorio called him Wilfredo and not Wilfred because, he said, it was easier for him to pronounce. Never mind too that the few available records from the now-closed PS 124 show a Wilfredo Benitez born in 1956 rather than a Wilfred born in 1958. September 12, 1958 is the date his family celebrates. It’s the date that makes him 17 when he defeated Cervantes and justifies the sign in front of his home that reads, “Campeon Mas Joven 17” – the youngest champion. It was a fake baptismal certificate with the misspelled name that caused the confusion according to Gregorio. Those backyard sessions at whatever age Benitez was helped create a fighter Jose Torres wrote was “Willie Pep, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Joe Louis all in one.” Those sessions undoubtedly contributed to the poor state of health he was in shortly after his career ended.

Gregorio’s training methods were often criticized and his credentials as a trainer came into question numerous times. Because of that, Gregorio frequently sought fights outside of Puerto Rico. The Benitez brothers kept winning however, and with each win, the critics were silenced. Wilfred, the youngest, was the most impressive. His head was in constant motion when he boxed and switching between the righty and lefty stance was no problem for him. His biggest influences were Muhammad Ali and Bruce Lee. He would even call himself “The Dragon” in later years. Early in his career, Benitez was still knocking opponents out. Armed with a solid punch, fully functioning radar, and a baptismal certificate with a forged date and an extra letter at the end of his first name, Benitez out-maneuvered, out-thought, and out-boxed the street-fighter-turned-champion from Colombia, Antonio Cervantes in front of a crowd that included his screaming classmates.

After the win, at a time when Angelo Dundee, Gil Clancy, Freddie Brown, Jesus Rivero, Cus D’Amato, and Amilcar Brusar were active, Hall of Fame matchmaker Teddy Brenner called Gregorio the best trainer in boxing. Jose Torres said what impressed him as much as the flawless defense was the fact that when Benitez threw his punches, he didn’t miss. On the day he beat Cervantes, Benitez was the best pure boxer in the sport. Slicker than Ali. Slicker than Miguel Canto. Slicker even than Philly junior lightweight, Tyrone Everett. With Ali past his prime, Canto stuck in that division of 110-pounders that never gets any credit, and Everett only a few months away from dying amid drugs, a transvestite, and a hail of bullets, Benitez was poised to become the star of the sport. As it turned out though, the Cervantes fight was the very beginning of the end for him.

Deprived of a normal childhood, once Benitez became a man, he started acting like a child. He purchased a new car and, if not for a pair of trees that stood strong along a winding road that wrapped around The Central Range, Benitez would have driven it off a cliff. With his new car wedged between the trunks of two trees, the fighter soon found himself wedged between managers, promoters, and people telling him how to spend his money. Gregorio sold the managerial rights to Bill Cayton and Jimmy Jacobs. The training duties went to Cus D’Amato, then to former boxing champion Emile Griffith, and Don King began dialing area code 787.

He stopped listening to his trainers and managers. Roadwork was something he used to do. Soon, money was something he used to have and the blame-game lasts until today. Papa Gregorio gets most of the blame. Benitez said his father would often point to a lot or a building and tell him that he had purchased that property for him and that he would get it when he retired. He never did. Gregorio’s gambling woes were widely reported and the insinuations were that it was his son’s money he was wasting away. Benitez’s older sister says those allegations were false. Gregorio had no control over her brother’s finances, she said. There was another reason, according to her.

In 1983 Benitez married the girl across the street. It was after the marriage that his money evaporated, his sister Yvonne says. Any rumors about his father wasting away Benitez’s money are false. “People like to talk,” she said. The stable of race horses his father kept were purchased with his own money and not that of his son’s. The confusion, Yvonne felt, may have been caused by the fact that the stable bore the name of the champion boxer.

When Benitez and his wife moved to New York, Gregorio said the fighter had a six-figure amount in the bank. As proof, he showed a reporter a Chemical Bank statement showing over two hundred thousand in liquid assets. The losses – both in the ring and in his bank account – started shortly after the marriage, he said.

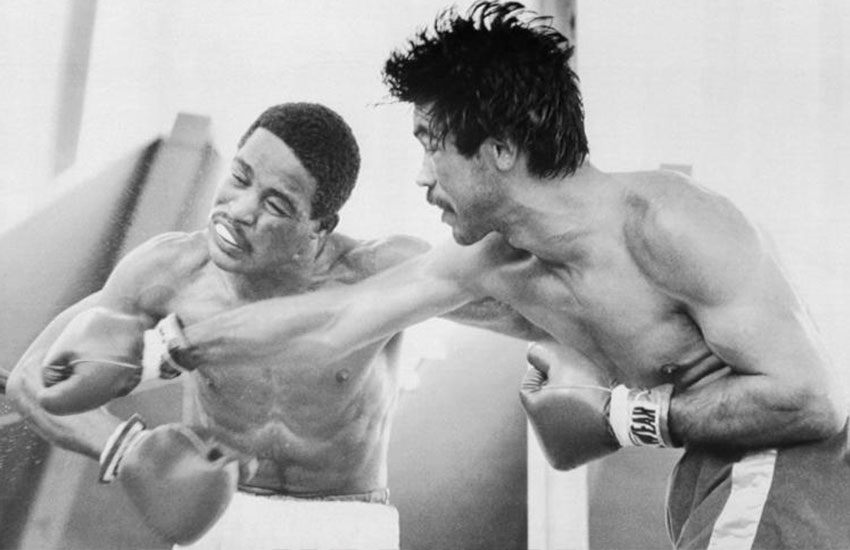

A fighter Sugar Ray Leonard called his mirror image was no longer a world class fighter by his mid-twenties. A fighter who once traded feints, jabs, and knockdowns with the destructive Thomas Hearns, and who turned Roberto Duran – a man Joe Frazier said reminded him of Charles Manson – into a passive and hesitant brawler, could no longer defeat even B-level fighters. Promoters began using him the way gardeners used stepping stones – something a prospect could easily walk over without getting scathed on his path to stardom.

Though he turned back one fighter with a pretty record in New York, he suffered a brutal loss to a legit prospect who was on the way to winning a belt. That fight in Montreal against Matthew Hilton was the first fight where Benitez was knocked out. Behind on the cards, Benitez was in the middle of a mini-rally and still trying to win when a series of wide hooks backed him into the ropes. A wide left hook crashed into his jaw and turned him into a bobble head doll just before his legs folded and he collapsed along with his career.

“I felt those punches too,” his mother said of the Hilton fight. “I told him it was time to stop.” She repeated her request months later when he was offered a match in Argentina. “But Mom,” he said while grabbing her hand. “I want to visit the homeland of Carlos Monzon.”

When Benitez arrived in Salta, Argentina, a place that, in some parts, looks like the Grand Canyon, he was expecting to fight Miguel Angel Arroyo and stay for a few weeks. Instead, he fought Carlos Herrera and stayed for more than a year. That he lost to Herrera was no surprise. Benitez needed help climbing into the ring. Local reporter Roberto Vitry attended the weigh-in and said Benitez was a shot fighter. In fact, he said Benitez failed the pre-fight physical. There was an equilibrium test before each fight where boxers are to form an “X” with their arms across their chest and stand on one leg. He couldn’t do it. Everyone in the room looked at each other, perhaps waiting for someone else to speak up. No one did. On top of that, Vitry continued, his license to box in Puerto Rico was suspended. Normally, the local commission would honor any outstanding suspension. Despite the suspension and the failed physical, Benitez was cleared to box. How much training he did is unknown. What most people saw him doing leading up to the fight was feasting on large steaks and boiled vegetables and attending Evangelical mass. How much he got paid is another issue.

When Benitez failed to return to Puerto Rico with his two handlers, word spread like mange throughout St. Just and Trujillo Alto, then made its way up to the United States and then back to Argentina. Word was Benitez was never paid for his fight in Argentina and he was stranded there because the promoter stole his passport.

The promoter of the fight, Miguel Herrera, says that though he was paid late, Benitez eventually got every penny of the $14,000 he was due and more. He says Benitez stayed in Salta voluntarily because, Benitez said, he would be thrown in jail for an outstanding debt the moment he stepped foot again in Puerto Rico. In an interview from his home just before his death, Herrera said his mistake was giving Benitez money just to avoid dealing with him. Benitez would show up at his office asking for money and the promoter said he’d instruct his staff to hand him a few pesos and not let him in. He paid Benitez’s hotel bill for months and his mother cooked meals for the fighter. When Herrera’s father died, they held the wake in their living room and Benitez, as he did in the ring against Leonard and Hearns during the referee’s instructions, stood in front of the casket, locked his eyes on it, and stared without flinching. For 24 hours, he stood without talking or sitting.

Benitez was smart in a hustler’s kind of way, said the promoter. He charmed the locals despite not speaking their dialect. It was not the first time he was accused of having charm. When Antonio Cervantes called him late in his career and advised him he was fighting too long, Wilfred, his mom said, told his former rival that he wanted “to be great like you, Kid Pambele.” And when Howard Cosell interviewed him in the ring after a match and asked him if the decision being split bothered him, Wilfred waved it off saying that, so long as he got the win, he didn’t care and that he just wanted to shake Cosell’s hand because Howard was a “great man.”

The locals in Salta affectionately called him “El Morenito,” which can be translated as, the cute little brown guy. He “pretended” he couldn’t speak or understand Castilian, “but I know he did,” Herrera said. Benitez spent his days like a vagabond, walking up and down the streets, telling anyone who would listen that he was waiting for his pay and that his passport was stolen. After a few months, the promoter said, he cut off Benitez. The fighter spent the rest of his days in Argentina crashing wherever he could, asking for handouts, and, at times, running at top speed throughout the streets until he collapsed on the ground from exhaustion. After resting, he would get up and run some more.

“One day, a man from Puerto Rico showed up,” Herrera said. The man, Leonardo Gonzalez, told Herrera he was sent by the government to bring Benitez back and, showing him a check, asked, “What do we owe you Mr. Herrera for your troubles?”

Whether Benitez was ever paid and how much is still a mystery. Benitez’s wife says she had a contract showing the amount offered was $25,000 and that the promoters never came close to matching that amount. It was also revealed that she had been communicating with Benitez while he was in Argentina and that she instructed him not to return until he collected the entire 25 grand.

Gonzalez said Benitez was underweight, malnourished, and incoherent when he found him. Upon returning home, the former champ was checked into a hospital where he remained for a couple of weeks. The local commission retired him. He was in no condition to box, they said. When he was released from the hospital, a 20-hour per week job training Olympic hopefuls that paid a salary of $800 per month awaited him.

Two years later, despite showing signs of suffering from post-traumatic encephalitis, Benitez awaited the opening bell in a ring at a Phoenix motel. His opponent was a fighter with zero wins in his career. Two months later, trained by Emanuel Steward, he fought in an indoor soccer arena on E 36th Street in Tucson. He lost. Before leaving Arizona, he filed for divorce. Then he headed north for his final two fights.

Five years after his final ring appearance, he was elected into the Hall of Fame. Four months after the induction ceremonies in Canastota, back home in Puerto Rico, he asked his mother for a piece of cake. Before she finished slicing it, Benitez was on the floor vomiting and in convulsions. He was taken to the Hospital Universitario in Rio Piedras and remained in a coma for about a week.

He never fully recovered and spent the following years under the alternating supervision of his mother, his sister Yvonne, and numerous medical professionals. While the family hoped for a miracle, his health deteriorated. He could no longer dress himself or tie his own shoes though, during lucid moments, he could still shadowbox when asked. After suffering a stroke years later, he rarely ventured much further than the front of his house. His daughter, who lived across the street, visited less frequently, according to his family. There were times few could understand what he was trying to say. During the few lucid days, he surprised those around him by singing Hector Lavoe songs and cheering for Miguel Cotto. More often were the sleepless days and nights and outbursts of tears.

“He told me to kill him,” his sister said. “With a gun.”

Gone was the perpetual smile that held up his thin mustache. Benitez was like a five-year-old cousin who greeted visitors at the door with a bright smile. In his eyes, everyone was great, everyone was beautiful. Whether they were good influences or bad, he was always glad to have people around him, his sister said. This man with no known enemies who once asked his sister to hold a gun to his head and pull the trigger because he didn’t want to live anymore may soon have that wish. Today he lays immobile in a bed with almost no friends and few visitors. A paraplegic surrounded by medical equipment with failing vision and little to no memory. His body is shutting down. His radar is malfunctioning.

Editor’s note: Jose Corpas’ second book, a biography of Panama Al Brown, titled “BLACK INK: A Story of Boxing, Betrayal, Homophobia, and the First Latino Champion,” is available now via Amazon and other leading online booksellers. He is currently at work on his next boxing book, tentatively titled “THE RIVALRY; Mexico vs. Puerto Rico.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds