Argentina

Remembering the Great Lightweight Champ Joe “Old Bones” Brown

He had a common name and an elegant ring manner. His career is justly celebrated but also largely forgotten. Anyone seeking to summarize in a few concise sentences the life and times of long-reigning lightweight champion Joe “Old Bones” Brown, who was 71 when he passed away on Dec. 4, 1984, is apt to be frustrated. The New Orleans native who held the division record with 11 successful lightweight title defenses until Roberto Duran (who had 12) came along requires thoughtful and thorough examination, a pugilistic doctoral dissertation as it were, to be fully appreciated. In this instance, a Cliff’s Notes condensation of what he did and how he did it simply won’t suffice.

Brown, who bore a physical and stylistic resemblance to the much-more renowned Sugar Ray Robinson, won the lightweight championship on a gritty, 15-round split decision over Wallace “Bud” Smith in New Orleans’ Municipal Auditorium on Aug. 24, 1956. Fighting from the second round on with a broken right hand – post-fight X-rays confirmed the fracture — Brown’s long-delayed, up-by-the-bootstraps bid for the title might have ended in still more disappointment had he not decided to ignore the pain and fire the overhand rights he had kept sheathed since incurring the injury. Brown scored a pair of knockdowns in the 14th round on big connections with his damaged paw, which proved to be the difference, at least in terms of public perception. Although referee Roland Brown and judge Charles Dabney had Brown cruising by respective margins of 12-3 and 9-3-3 in rounds, the other judge, Freddie Adams, had Smith up by 7-6-2. The unofficial Associated Press scorecard had Brown barely ahead at 8-7, while United Press International favored Smith by the same margin.

“I broke the right hand in the second round when I popped him on the chin,” Brown said. “I gambled in the 14th by throwing the first right since the second round and it really hurt. I had to gamble; it was the only way to win.”

Although Smith’s trainer, Adolph Ritacco, complained that his fighter had been the victim of a “hometown decision,” Brown so dominated the rematch, on Feb. 2, 1957, in Miami Beach that Ritacco beseeched the ring physician to halt the bout after 10 rounds with Smith battered and bleeding on his stool. The request was granted, giving Brown his third victory over Smith in as many tries, including a 10-round unanimous decision in a non-title bout on May 2, 1956, in Houston.

Once perched upon the lightweight throne, Brown – who turned pro at 17 on Sept. 3, 1943, thus making for a 13½-year, 99-bout journey to his title shot – was determined to reign a good long time. And he did just that, logging those 11 winning defenses (six by KO or stoppage) against some of the finest lightweights during a bountiful time for the 135-pound division. He was much more effective than he had been on the way up, too, having demonstrated increased punching power after taking on a new trainer, Bill Gore, in 1955. Although Brown still maneuvered as nimbly as such other New Orleans-reared dandies as Willie Pastrano, Pete Herman and Ralph Dupas, he now knew when and how to sit down on his punches for maximum leverage.

“I think Joe Brown, once he added that knockout punch, was phenomenal,” said Les Bonano, 73, a longtime New Orleans promoter and manager. “He was a master technician with a great sense of spacing. Call me biased or whatever, but, as a lightweight, I really don’t think Floyd Mayweather would have beaten the best of Joe Brown.”

Still, there are those who contend that history has not been as kind to Brown as his achievements merit. “He never got the attention or the glory that some other guys who maybe weren’t as good got,” Bonano said. “He should have been so much bigger than he was.”

That could be because of the years Brown, who served honorably in the Navy for 21 months during World War II and participated in seven Pacific invasions, squandered by fighting for miniscule purses on the Deep South “chitlin circuit” during the Jim Crow era. Even the night he dethroned Smith, before a sellout crowd of 8,000, the referee and both judges were black and the seating was segregated, with whites on one side of the ring and blacks on the other. It could have been because of the unadorned plainness of his name, which Sugar Ray Robinson’s trainer, George Gainford, suggested he spruce up with something catchy. Sensing that Gainford might have been onto something, Brown promptly dubbed himself “Old Bones,” a moniker which did serve to elevate his profile somewhat, as the “Ole Mongoose” had done for Archie Moore.

Mostly, though, Brown was bogged down by the burden of having fought so often against so many tough customers in the formative stages of his boxing life, incurring occasional defeats that suggested he was a good, honest tradesman but not someone who was destined to become a living (or even deceased) legend. The night he took on Smith for the title, his 70-18-11 record, with 29 victories inside the distance, hardly hinted as someone who had the makings of an all-timer. At 30, it seemed improbable that he would suddenly find a way to not only move up to his sport’s highest level, but to do so by leaps and bounds.

Writer Mike Plunkett, in describing Brown’s delayed-reaction breakthrough, put it thusly:

Sometimes greatness is obvious. It explodes out of the gate, often with a particular look and feel to it while other times the ascent of a great fighter in the making is more gradual, punctuated by moments that over time reveal something special.

But other times greatness shows up in disguise, arriving before it is recognized and missed when it is gone. Where prizefighting is concerned, the less obvious sort of greatness can sometimes kick-in for a fighter after years of setback and disappointment, the end result the finished product of lessons learned at the school of hard knocks, and for a time such a fighter bears little to no resemblance to the struggling pugilist he once was. Such was the career of former world lightweight champ Joe “Old Bones” Brown, an example of unlikely and unexpected ring greatness.

Father Time, of course, is the opponent no fighter who doesn’t retire while still on top can stave off indefinitely. The sands in the hourglass of “Old Bones’” exhilarating prime were about to run out the night he took on a young, hungry challenger from Puerto Rico, Carlos Ortiz, on April 21, 1962, in Las Vegas. Ortiz – who would go on fashion a splendid 10-2 record with seven KOs, spread over his two lightweight reigns – easily dispatched Brown’s surprisingly creaky old bones en route to a one-sided unanimous decision.

Brown would not fight for a world title again, but neither would he return to the pre-boxing profession, carpentry, he had learned as a boy from his father. He hung around for eight-plus years as an international vagabond who took bouts in Mexico, Mozambique, South Africa, Finland, Italy, Puerto Rico, Colombia, England, Jamaica, Panama, Venezuela, Brazil and Argentina while again taking short-end money by trading on what remained of his reputation. During his long goodbye, Brown, who was three months shy of his 44th birthday for his final fight, a 10-round, unanimous-decision setback to 23-year-old Dave Oropeza in Phoenix on Aug. 24, 1970 – exactly 14 years since his dethronement of Smith – went a scuffling 20-24-2. And it wasn’t just the aging process that marked his deterioration as a fighter. His heart apparently had gone out of his work as well.

Popular British heavyweight Henry Cooper, who had seen Brown at his best, and also bore witness to his professional death throes, noted in Henry Cooper: An Autobiography, that there came to be “little pride left in (Brown’s) performance” as he tried to compensate “for all the hungry years when he had been forced to fight for peanuts.”

When the bad times for Brown ended, as had the good times, all that was left was for a verdict to be rendered for posterity. For the most part, that decision has been far more positive than negative. Among the many highlights of Joe Brown’s incredible journey are:

*Induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1996.

*Induction into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame in 1976.

*Induction into the Greater New Orleans Sports Hall of Fame in 1977.

*Being named The Ring’s Fighter of the Year for 1961.

*Participation in The Ring’s 1961 Fight of the Year (a rousing 15-round unanimous decision over England’s very capable Dave Charnley on April 18 of that year in London).

*Getting the No. 36 slot on NOLA.com’s list of the 51 greatest Louisiana athletes of all time in 2014, which is especially notable as he is the only boxer to make the cut.

*Breaking the legendary Benny Leonard’s lightweight record of nine consecutive successful title defenses, with 11, since broken by Roberto Duran with 12.

If there is anything to still debate about “Old Bones,” it’s an indisputably accurate reading of his final record. BoxRec.com lists it at 116-47-14 (52), the IBHOF at 104-44-13 (47) and Wikipedia at 105-46-13 (47).

To comment on this article at The Fight Forum, CLICK HERE.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

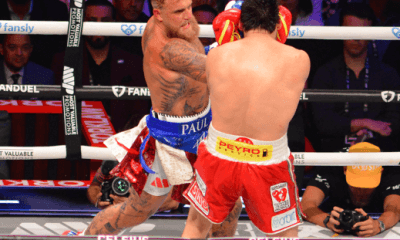

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates