Argentina

“Jess Willard”: A Book Review by Thomas Hauser

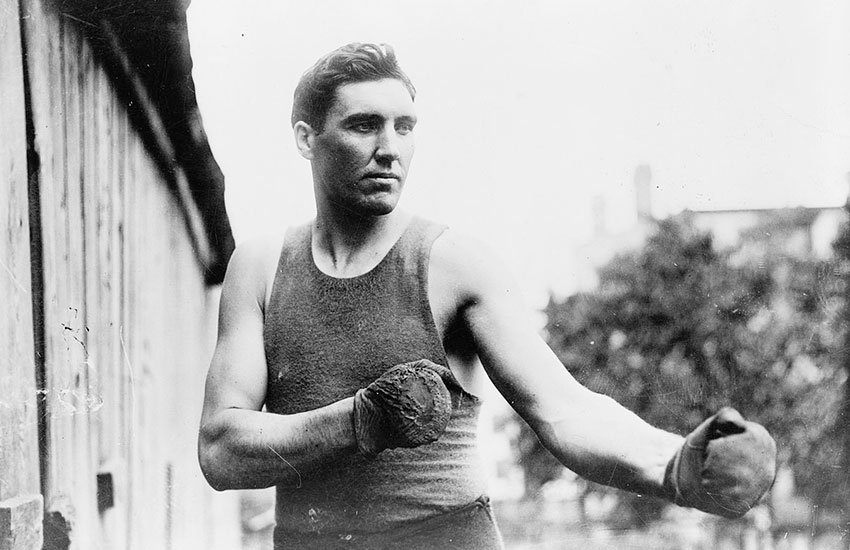

Jess Willard’s ring career was defined by two fights: an April 5, 1915, victory over Jack Johnson in Havana, when he fulfilled his destiny as a “great white hope,” and a brutal knockout defeat at the hands of Jack Dempsey on July 4, 1919, that heralded the dawn of a new era in sports.

“Jack Johnson and Jack Dempsey,” Arly Allen writes, “are remembered as great American heroes. But like an old book between two elaborate bookends, Willard is now forgotten.”

Jess Willard, published by McFarland & Company, is Allen’s attempt to remedy that oversight.

Willard was born in Kansas on December 29, 1881. His father died before Jess was born, leaving a widow with three sons – ages 11, 9, and 6 – and a fourth on the way. Jess’s early years were spent in Pottawatomie County. He quit school at age twelve and found work herding cattle and breaking wild horses. Much of his later life was spent in California.

Willard was 28 years old when he walked into a boxing gym for the first time. He stood 6-feet-6-inches tall, weighed roughly 230 pounds, and had never seen a professional fight. Years later, when asked how he got into boxing, he answered, “I never had any thought of it until Johnson beat Jeffries in Reno.”

Willard’s first professional bout was contested on February 15, 1911, in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, and ended in a disqualification loss when he threw his opponent to the canvas. The Daily Oklahoman wrote of that fight, “Willard behaved in a most ignorant manner in the ring. He probably knew less about what he should do than any boxer that ever stepped inside the ropes.”

More significantly, as Allen writes, “Most men, when they get involved in boxing, have been involved in fights and violence during their childhood which prepared them for the rigors of the ring. Boxing was often their best alternative to prison. Jess Willard was different. His strength was prodigious but his temper was mild. Willard did not like to fight. Most of his opponents enjoyed boxing and were happy to destroy their opponents in the ring. Willard did not and often said that, if his opponent was not hurting him, he saw no reason to hurt his opponent.”

Allen then notes, “Willard’s exceptional size made few men want to fight him. His non-aggressive style led to boring fights. His temperamental habits made him a manager’s nightmare. His physical ability carried him to victory. [And] his mental attitude left him vulnerable to defeat.”

On August 22, 1913, in Willard’s twenty-first professional bout, his attitude toward boxing grew even more ambivalent when he knocked out a 1-and-2 opponent named Bull Young (who he’d knocked out twice before in previous fights). Young lapsed into unconsciousness and died the next day. In the months that followed, Willard was charged with manslaughter but was acquitted.

Willard was 33 years old and weighed 238 pounds when he fought Jack Johnson. Papa Jack, well past his prime by then, was four years older and entered the ring at a career high of 225 pounds, an indication that he wasn’t in the best of shape.

After Willard beat Johnson, writer Damon Runyon told one-time lawman Bat Masterson (who served as a timekeeper for John L. Sullivan’s fights against Jake Kilrain and James Corbett), “Jess Willard can’t fight a lick.”

“No, he can’t,” Masterson answered. “But who’s going to beat him?”

For a while, no one had a chance. Willard simply refused to fight.

He had emerged from his victory over Johnson as one of the most famous and admired men in America. But the fight had failed financially and Willard needed money badly. So he moved quickly to the vaudeville circuit followed by appearances in “Wild West” shows, where he made as much as $6,000 a week. He fought only once during the next 51 months, surviving that encounter with an unimpressive “newspaper decision” over Frank Moran.

Meanwhile, Willard was squandering his popularity. Not only didn’t he like fighting, he was, as Allen recounts, “totally unprepared for the reception that awaited him [after he defeated Johnson]. Before the fight, he was just an ordinary man, taller than most but nothing special. But because he had won, he became a famous celebrity. Willard did not know how to handle his fame. As champion, he always felt uncomfortable around crowds. He was not a great people person. He did not delight in the adulation of his fans and tried to avoid it as much as he could.”

Willard was 37 years old and weighed 243 pounds when he fought Jack Dempsey in Toledo, Ohio. Dempsey was 13 years younger and weighed 56 pounds less. The temperature was 110 degrees when the bout began at 4:09 PM. The fight was scheduled for twelve rounds. Dempsey brutalized Willard, who failed to answer the bell for the fourth round.

Forty-six months after losing his championship, Willard returned to the ring at age 41 and knocked out Floyd Johnson at Yankee Stadium in eleven rounds. Two months after that, on July 12, 1923, he fought Luis Firpo at Boyles 30 Acres in New Jersey and was knocked out in the eighth round in front of an estimated 100,000 fans, the largest crowd to witness a prizefight up until that time.

That was Willard’s last fight. His final ring record stands at 22 wins, 5 losses, and 1 draw with 20 knockouts and 3 KOs by.

It’s hard to separate fact from fiction when reconstructing long-ago boxing history, but Allen does a pretty good job of it. His book is extensively researched. There’s some interesting material on the crowning of Luther McCarty as the “white heavyweight champion of the world” in 1913 and McCarty’s death in the ring later that year.

There’s also a lot of material on Willard’s business ventures (most of which failed) and other outside-the-ring activities.

“I believe Jess was a square dealer,” Jess Stone (a longtime friend of Willard’s) said. “But I don’t believe he thought anybody else was. That made him a tough person to do business with.”

It also led to Willard being a magnet for breach of contract lawsuits and other complaints.

There are times when Allen’s fondness for Willard calls the objectivity of his writing into question. Allen persuasively assembles the evidence that supports the legitimacy of Willard’s knockout victory over Jack Johnson. Less credibly, he litigates the case for Willard being done in by injustice in his bout against Jack Dempsey.

Allen raises the dubious claim that Dempsey’s gloves were loaded, points to fouls that Dempsey committed during the fight, and argues that Dempsey should have been disqualified for leaving the ring after round one when he thought the fight was over.

“Willard was robbed of his title in the Dempsey fight,” Allen states. “That is established.”

Not really.

As Allen ultimately concedes, there’s no sound probative evidence that Dempsey’s gloves were loaded.

Dempsey fought within the rules as they were widely interpreted and enforced at that time.

And Dempsey leaving the ring after round one actually worked to Willard’s advantage because it gave Jess more time to recover from the brutal punishment that he absorbed in the first stanza.

Here, Willard’s own thoughts are instructive.

“That story about a body blow is all wrong,” Willard said of the Dempsey fight. “There may have been a few landed after I was dazed by the first left hook to my jaw, but they didn’t affect me any. That left hook landed clean on the point of my jaw. From that time on, I didn’t know whether I was in the ring or in a cornfield. That was the blow that started me on defeat. I was virtually knocked out before I had started. I felt physically able to continue [when the fight was finally stopped]. But my head wasn’t clear and my eye was closed, and I realized it would have been useless for me to attempt to box while half-blinded.”

Jess Willard by Arly Allen is the most thorough biography of its subject to date. It’s fitting to give the final word to Willard himself, who once said, “I am no believer in violence. In bringing up my kids, I say, ‘What’s the use of spanking them just because they make noise? If you spank them, they only make more noise.’”

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at thauser@rcn.com. His next book – There Will Always Be Boxing – will be published by the University of Arkansas Press this autumn. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

To comment on this article at The Fight Forum, CLICK HERE.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds