Argentina

Argentine Legend Carlos Monzon: Revered and Reviled

Sometimes the story you think you’re going to write takes a swift and decisive turn, as can be the case in boxing, where the outcome of a fight that

Sometimes the story you think you’re going to write takes a swift and decisive turn, as can be the case in boxing, where the outcome of a fight that seemingly is all but decided can swing the other way with a single well-placed blow.

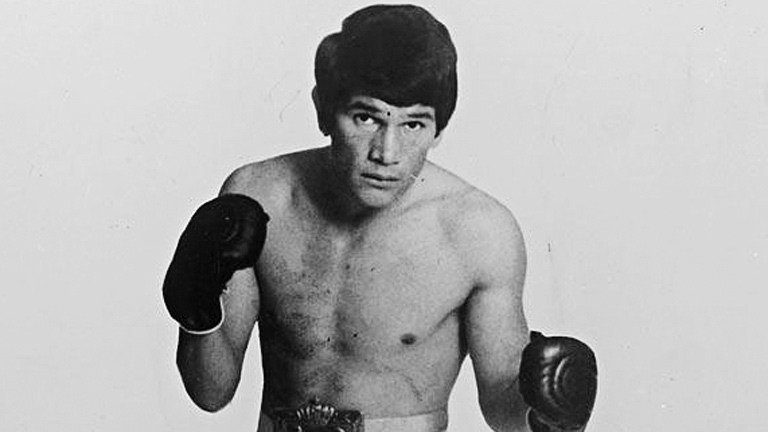

My original notion was to commemorate the career of Argentina’s greatest boxer, the late Carlos Monzon, who wrested the middleweight championship from Italy’s Nino Benvenuti on an emphatic, 12th-round knockout on Nov. 7, 1970, at the Palazzetto dello Sport in Rome. Toward that end I again watched the tape of Monzon’s performance that night against his fellow future Hall of Famer, for the purpose of assessing his rightful place on the list of the division’s all-time greats, a Who’s Who of the ring that includes the esteemed likes of Harry Greb, Stanley Ketchel, Sugar Ray Robinson, Charley Burley, Marvelous Marvin Hagler and, of more recent vintage, Bernard Hopkins and the still-active Gennady Golovkin. There are those who would place Monzon at the front of that exclusive line.

But while Monzon was undoubtedly an all-time great, proclaimed as such on the cover of the Aug. 8, 1977, issue of Sports Illustrated by an action photo of his final bout, a 15-round unanimous decision over Colombia’s Rodrigo Valdez and a headline that read Monzon The Magnificent: Middleweight Champ Wins His 83rd in a Row, more current headlines of a different sort caused me to wonder if my planned celebration of the genius of his craft should dwell more with his many failings as a human being.

“Sexual harassment” and “domestic abuse” are more hot-button topics today than they were decades ago, before the rise of female empowerment brought those issues out of the shadows and into the glare of widespread public scrutiny. But there is a significant difference between the reprehensible but non-violent abuses large inflatable water slides of power attributed to movie executive Harvey Weinstein and those of Monzon, who literally battered his various wives and mistresses whenever he failed to exercise proper impulse control. That pattern of unchecked aggression was culminated when Monzon, a beloved national hero in Argentina, was convicted of murder in 1988 after he strangled his second wife, Uruguayan model Alicia Muniz, and threw her off the second-floor balcony of a resort hotel at which the couple was staying.

But millions of Monzon’s countrymen continue to revere their presumably disgraced idol, who died in a car crash, at age 52, along with passenger Geronimo Domingo Mottura, on Jan. 8, 1995, while on unsupervised “furlough” from prison. Evidently the penalty for homicide is less severe in Argentina for those who have had statues erected in their honor.

That statue, located along the coast of Santa Fe, Argentina, depicts Monzon, his arms thrust upward in victorious exultation. Called the Costanera, it purportedly is “illuminated by the light of everlasting glory.” One Argentine writer, musing about the message the statue’s place of prominence continues to espouse, holds that “…nobody can judge (Monzon). His life, as well as his boxing role, has always been a work of art. Standing in front of his statue is enough to remember him while avoiding tears running down our faces.”

For those unwilling or unable to differentiate Monzon the champion from Monzon the killer and serial thumper of women, such rationalization is fairly commonplace. Hero worship does not allow for much introspection for those who refuse to acknowledge personality warts on their idols, nor is it confined to any particular country, culture or class. Boxing, and the sports world in general, is liberally dotted with the names of famous athletes who have disrespected women, and worse, because they felt they somehow were above the laws of civilized society that apply to everyone else. Football stars Aaron Hernandez and Lawrence Phillips, both now deceased, committed murders, and O.J. Simpson was accused but not convicted of a double murder. Tom Payne, the former University of Kentucky basketball star, is still incarcerated after being convicted of multiple rapes. Former NFL running back Ray Rice literally lost his career after a video surfaced of him scoring a one-punch knockout of his girlfriend (now wife) and dragging her out of a hotel elevator by the hair.

Jack Pemment, who holds a master’s degree in psychology, wrote a scholarly treatise on boxers and domestic violence that explains but does not condone such (usually) well-publicized incidents, while also holding that the discipline expected of a fighter also can mitigate the urge to yield to feelings of rage against his wife or significant other.

“Boxing is intimately linked with working class backgrounds and poverty,” Pemment wrote in Psychology Today. “The connection between poverty and boxing is a phenomenal case study in itself.” He cited three possible causes for individuals to become “irrationally reactionary,” one being a fear of a fighter returning to his impoverished roots, another being a successful fighter’s developing sense of entitlement and, lastly, stress and personality disorders that are connected to violent behavior.

But, Pemment concludes, “there is no formula for determining if (such disorders) can result in impulse control problems.” Furthermore, he states that “there have been numerous instances where joining a boxing gym has literally helped to keep kids off the street and out of gangs. This has the immediate effect of preventing children from being exposed to criminal violence. In the infinitely complex quagmire of human behavior, there will always be exceptions to these things (that lead to domestic violence), but this is why I think boxing has probably helped to reduce aggressive outcomes outside the ring, rather than encourage them.

“To be sure, there are people that have been beaten by boxers (Floyd Mayweather is the highest-profile example), and I do not want to undermine the plight of the victim. There is no excuse for domestic violence, and I still maintain that (ideally) boxers should have a greater sense of self-awareness of the damage they can cause, which is perhaps why they should be held to a higher standard. Domestic violence is an abhorrent endemic social problem that impacts far too many people on a daily basis. If boxing was somehow removed from the equation, the numbers would not drop.”

Which is a fancy way of saying that the fault does not necessarily lie in any individual’s profession or station, but to that person’s sense of morality. But just as Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby are too high-profile to evade close scrutiny forever, so, too, are such pugilistic strayers from accepted norms as Monzon, Mayweather, Mike Tyson, the late Jake LaMotta and a notable few others. Their fans might laud what they do inside the ropes, but that only comprises a portion of who they truly are as a whole. Perhaps the entirety of a person’s character should be taken into account before we relinquish our hearts like love-struck teenagers.

Monzon’s place on a boxing pedestal is forever ensured, and so is it for Mayweather, he of the 50-0 record and record-shattering gross revenues. “Money’s” place in boxing history is assured, but that should not fully absolve him of another kind of history, which includes seven separate incidents of domestic abuse against five different women dating back to 2001, one of which resulted in a 90-day prison sentence. Mayweather’s feeling of entitlement is such that he successfully sought to bar two female reporters, HBO and ESPN’s Michelle Beadle and CNN’s Rachel Nichols from being credentialed to cover his May 2, 2015, megafight with Manny Pacquiao because they brought up the less savory aspects of his life which he would prefer not to be raised.

Tyson, of course, served three years for the rape of a teenaged beauty pageant contestant, which he has denied committing. Interviewed by Fox News’ Greta Van Susteren, he denounced the victim on television as a “slimy bitch” and “lying reptilian,” and while reiterating that, while he was falsely convicted, he’d like to “do” her and her mother then as a form of pay-back. This is the same guy who once bragged that “the best punch I ever landed” was on Robin Givens, his first wife.

LaMotta, the “Bronx Bull” whose sometimes sordid life was chronicled in the 1980 Academy Award-winning film Raging Bull, was 95 when he passed on Sept. 19. Asked once by the second of his seven wives, Vikki, why he felt the need to beat her, LaMotta said it was because he “loved” her and he thought it would serve to frighten her into staying with him.

Everyone has faults, some more pronounced than others, and we all should take a good, hard look in the mirror before casting stones at anyone else’s glass house. It’s OK to admire a fighter for what he does inside the ropes while entertaining us. But it’s always a slippery slope upon which we venture when that admiration causes us to lose sight of the bigger picture, which is how each and every one of us places in the tapestry of human existence.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates