Featured Articles

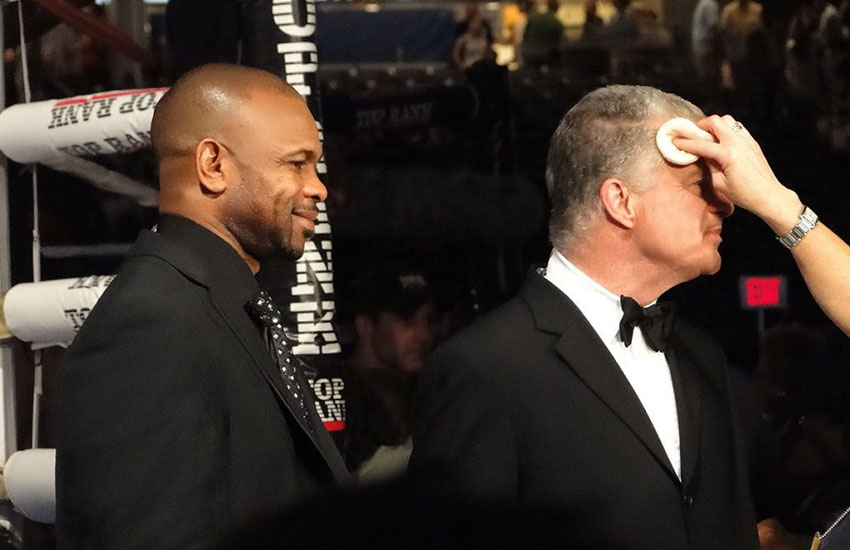

Jim Lampley Wistfully Recalls The Roy Jones That Was

Kryptonite could bring the Man of Steel to his knees. Greek mythology’s Achilles was unconquerable in battle, but he could be brought down

Even Superman was not wholly impervious to danger and the specter of defeat. Kryptonite could bring the Man of Steel to his knees. Greek mythology’s Achilles was unconquerable in battle, but he could be brought down if struck with a strategically placed blow to an unprotected heel.

The only two boxers that longtime HBO blow-by-blow announcer Jim Lampley has observed who were so preternaturally gifted that they superseded the normal bounds of human excellence were the younger, nearly-perfect versions of Muhammad Ali and Lampley’s current HBO broadcast partner, Roy Jones Jr. But each of those superheroes of the ring eventually encountered a relentless opponent that incrementally stripped away the insulating layers that had made them such very special fighters. It was not so much another living, breathing human being who served as the kryptonite that revealed their fallibility as the unseen thief that comes silently in the night, stealing tiny bits and pieces of their exquisite talent until only a shell of what had been remained.

On Feb. 8, in his hometown of Pensacola, Fla., the 49-year-old Jones (65-9, 49 KOs) presumably brings down the curtain on his 29-year professional boxing career when he takes on a carefully selected designated victim, Scott Sigmon (30-11-1, 16 KOs), in a scheduled 10-round cruiserweight bout. The plan is for Jones, a world champion in four weight classes and a surefire first-ballot International Boxing Hall of Fame inductee whenever he becomes eligible, to go out in a blaze of out-of-the-spotlight glory. But if boxing history tells us anything, it is that not everything goes according to plan even for those who have enjoyed the panoramic view from the summit of Mount Pugilism. Mike Tyson, 19 days from his 39th birthday, never fought again after he was stopped in six rounds by plodding Irishman Kevin McBride on June 11, 2005, and Bernard Hopkins, 29 days from his 52nd birthday, was finally obliged to acknowledge the natural laws of diminishing returns when he was knocked out in eight rounds by Joe Smith Jr. on Dec. 17, 2016.

“I have read reports that he is saying this will be his last fight and that’s very encouraging and gratifying to me,” Lampley said of his friend’s farewell appearance, which by any reasonable criteria is coming a good dozen years after what should have been his career’s optimal expiration date. “I don’t know of a single soul in our little universe of boxing who wants him to keep doing this. We all know realistically that it’s certainly of no value to his legacy as a fighter.

“I’d be lying if I said that I never once made a comment to him or tried to engage him in a conversation as to why he was still doing this. The last time I did so he made clear to me that, in his view, it wasn’t something he had to defend to me. He was going to do what he was going to do and that within our friendship it was important for me to accept that. I accepted it. Probably five or six years have gone by since the last time I had a discussion with him about it.”

The most revered gods of war are held to a higher standard than fighters of a lesser pedigree. It thus should come as no surprise that those members of boxing’s most exclusive club are sometimes resistant to step away from something that always has defined them more than anything they could ever do outside of a roped-off swatch of canvas.

“You always think of yourself as the best you ever were,” Sugar Ray Leonard, he of the four announced retirements that didn’t stick, once said. “Even if money is not an issue, and you have other options, you never lose that belief in yourself as a fighter, particularly if you’ve been to the very top of the mountain. (Being retired) eats at you. It’s hard to finds anything else that gives you that high.”

Ali lost three years of his prime to his banishment for refusing to be inducted into the Army during the Vietnam War, but, unlike the stop-and-start Leonard, Jones’ response to every warning sign that he was on the downward slope of that figurative mountain was to keep fighting on, all the while holding fast to the distinctive style he shared with Ali. It was those non-traditional mannerisms, which worked so spectacularly well when Ali and Jones were at their best, that sometimes produced disastrous results when their fundamental deficiencies were exposed.

“The direct comparison is Ali,” Lampley said of the closest thing to Jones he has known, both in good times and not so good. “I’ve said a thousand times that there were only two fighters in the history of the sport, certainly since I’ve been watching boxing, whose physical talents were so overwhelming that they could take apart the tool kit and put it back together in any way they wanted – lead with a hook, lead with a straight right hand, dispense with the jab, back away from punches rather than duck and slip. Ali could do that for a while. Roy could do that for a while. But nobody can do that forever.

“That is why the tool kit is what it is, for normally talented human beings. It’s your protection in the ring. For a long time Ali and Roy didn’t need that protection. Then, when their bodies lost something and they weren’t so overwhelmingly physically superior anymore, they didn’t have that tool kit to protect them.

“The perfect and most graphic example is if you watch the first Roy Jones-Bernard Hopkins fight (on May 22, 1993). It’s all Roy Jones. If you watch the second Jones-Hopkins fight (on April 3, 2010), that’s all Bernard Hopkins. The difference is that, during the passage of time, Roy felt he never needed to employ the tool kit. Bernard, of course, was passionate about learning and amplifying and exercising everything in the tool kit. The amazing thing to me is that Roy knows the tool kit. He knows it as well as anybody. He demonstrates that as an expert commentator. He sits there and talks about what normal fighters should do, using the normal craft of boxing. But he never felt compelled to use any of that throughout his own career.”

For some, the best of Roy Jones Jr. was on display the night he picked apart fellow future Hall of Famer James Toney to win a wide unanimous decision on Nov. 18, 1994. For others, it was his utter domination of Vinny Pazienza en route to scoring a sixth-round stoppage on June 24, 1995. The highlight of Jones’ deconstruction of Paz was a sequence in which, holding onto the top ring rope with his right glove, he fired eight consecutive left hooks in a machine-gun burst, all eight connecting with the target’s increasingly busted-up face. It was an expression of creativity akin to a musical genius who spontaneously reproduces the rhythm in his head only he can hear. Think Miles Davis at the Newport Jazz Festival, Ray Charles at the Apollo, Count Basie at Carnegie Hall.

Said Seth Abraham, then-president of HBO Sports: “George Foreman (who did color commentary for Jones-Pazienza) told me after that fight only Roy fights like a great jazzman plays. He improvises. He does riffs. I thought that was such an insightful way to describe Roy Jones.”

For a majority of fight fans, however, the most lasting memory of Roy Jones Jr. came on March 1, 2003, when the man who began his pro career as a middleweight and won a world championship in that division, later adding super middleweight and light heavyweight titles, boldly moved up to heavyweight to challenge the much-larger but less-skilled WBA champion, John Ruiz. There was a school of thought that Ruiz was too big and strong for Jones and another that Jones’ speed and mobility would surely carry the day because talent is usually a more precious commodity than size.

It was, of course, no contest as Jones – who went off as a 2-1 favorite — darted in and out, pounding on the bewildered Ruiz as if he were just another heavy bag in the challenger’s Pensacola gym. The margins of victory on the official scorecards – eight, six and four points – scarcely reflected the level of Jones’ dominance.

But, as is sometimes the case, the showcase conquest of Ruiz actually marked the beginning of the end of Jones as a larger-than-life source of wonderment. Curiously, at age 34 he elected to return to light heavyweight instead of a more sensible reduction to cruiserweight. While it had been a bit of a chore to bulk up the right way to 193 pounds for the weigh-in for Ruiz (he was 199 the morning of the fight), paring 20-plus pounds of muscle was infinitely more taxing. In retrospect, it now seems apparent that Jones was never the same after the happy glow of his rout of Ruiz had subsided.

“He took 31 pounds of muscle off (that figure might be a tad excessive) and that can’t be done without a residue of damage,” Lampley said. “It just can’t be done, and he suffered from that, maybe permanently. I don’t know what his thought process was, why he thought it was important to come all the way back down to light heavyweight. I certainly get it that he was never a natural heavyweight. For him to remain in the heavyweight division would have been an aberration. I guess he figured that, as a big-name fighter, for him to fight as a cruiserweight, which was not a prestigious weight class at the time, would be like saying, `I’m going to go over here in the back closet and fight where you won’t see me.’ Maybe that was an option that was not acceptable to him.”

In his first post-Ruiz bout, Jones retained his light heavyweight titles on a disputed majority decision over Antonio Tarver. He followed that with a two-round TKO loss to Tarver in the second of their three fights, but that could be dismissed as a bolt of lightning that occasionally can fell even elite fighters. But it was in his next outing, on Sept. 25, 2004, against Glen Johnson, that it became apparent to all that Roy Jones Jr. had descended from on high into the ranks of the merely mortal. Johnson, a fringe contender whose willingness to mix it up superseded his good but hardly remarkable talent, gave Jones a taste of his own butt-kicking medicine until he literally knocked him cold to win on a ninth-round knockout.

For Lampley, it was like a repeat of another fight from another time, when Jones’ magnificent stylistic predecessor suffered a similar head-on crash with boxing’s crueler realities.

“The night that Ali fought Larry Holmes (Oct. 2, 1980, at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas) I heard – and I’ll never forget it – the greatest single line of boxing commentary ever, and it came from someone who wasn’t involved in boxing,” Lampley recalled. “I was in the executive suite at ABC in New York, watching the fight, which was one of the sport’s rites of passage. We all know the culture of boxing, the old giving way to the new. Ali vs. Holmes was just such a rite of passage. It had to happen the way it happened.

“In the late rounds, when Holmes was beating Ali to a pulp, I got a little jab to my rib cage. I looked to my right and it was Mick Jagger. Mick said to me, `Lamps, you know what we’re watching?’ And I said, `No, Mick, what are we watching?’ He said, `It’s the end of our youth.’ And it wasn’t just that for us, but for the whole audience.”

The night that Jones, who once had towered over boxing as if he were the Colossus of Rhodes, was pummeled by Johnson, reminded Lampley as no fight ever had of Ali-Holmes. Nothing would ever be quite the same again.

“How else could a relatively ordinary fighter, albeit one with a big heart and a big motor like Glen Johnson, knock the great Roy Jones into next week the way he did? That was not the Roy Jones we had seen before. It was a different person.”

But, as Sugar Ray Leonard noted, it is human nature to think of ourselves as the best we ever were. The Roy Jones Jr. who will answer the opening bell against Sigmon will have his hands low, leaning back from punches instead of stepping to the side, because that is who he was at his best. To do otherwise would be a concession to mortality, an acknowledgment that all glory is fleeting, and perhaps his last waltz around the ring will turn out better than it did for Tyson and for Hopkins. But whether it does or doesn’t, his enshrinement into the IBHOF in Canastota, N.Y., is assured.

“What I don’t understand is why, once the handwriting was on the wall – Glen Johnson, Danny Green, Denis Lebedev – why keep going after that?” Lampley said of Jones’ refusal to leave the arena when so many were urging him to do so. “That’s what I don’t understand, and never will. He’s never tried to explain it to me and I’m too respectful of him to have pressed the issue. I did at one point say to him, `I think you’re hurting your legacy and you’re not accomplishing anything here.’ He basically said to me, `That’s my business, not yours.’ So I said, `OK.’

“When it comes right down to it, I think there’s a part of Roy Jones who still thinks, and always will, that he’s still that Roy Jones, despite all evidence to the contrary. And he’s earned the right to think that way.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review5 days ago

Book Review5 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds