Asia & Oceania

The Fifty Greatest Bantamweights of All Time: Part 4, 20-11

I need to talk to you about George Dixon.

I placed him at number four on my featherweight list. He made double-figures for title defenses at this poundage and he conquered many excellent featherweights

I need to talk to you about George Dixon.

I placed him at number four on my featherweight list. He made double-figures for title defenses at this poundage and he conquered many excellent featherweights in what was a stacked era. The weight limit is a confusing issue around this time as the featherweight and bantamweight limits seem almost interchangeable as various champions and promoters shuffle them in order that they might best fit the required physique, but whatever the defined limit in that era, I respect it.

At bantamweight, Dixon won exactly one title fight at the then limit.

Modern historians and writers have tended to subsume fighters into the modern rendering of weight classes. In other words, although Dixon was a career featherweight, they treat many of his fights as bantamweight contests for the purposes of their ranking of him. This makes his 1893 victory over Solly Smith, for example, a bantamweight contest when it was recognized, in its own time, as a featherweight clash.

Not so for this list. Here, Dixon is given recognition in keeping with his own era’s rules. So he is ranked among the very best featherweights in history but he does not appear on this bantamweight list.

He very nearly made an appearance at number fifty, but in the end, that would have been more about justifying my appraisal than presenting as legitimate top fifty as I could possibly manage. Charley Phil Rosenberg was just more deserving.

So forgive me this quick explanation.

Here’s the first part of the top twenty:

#20 – Jimmy Carruthers (1950-1962)

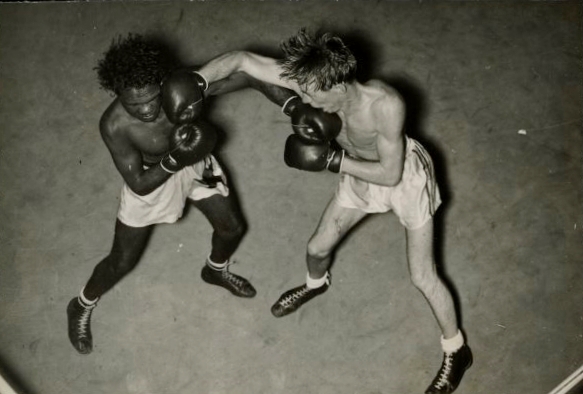

One of the greatest Australian fighters, Jimmy Carruthers (pictured) never lost a fight at bantamweight and retired the champion of the world at just twenty-five years old.

It would be an exaggeration to say he appeared out of nowhere to annex the championship, but probably not by much. Carruthers was already a sensation in his native country, but the opposition certainly did not justify the hype (Elley Bennett, a good fighter, notwithstanding). Nevertheless, when he departed his shores for the South African capital in 1952 with champion Vic Toweel on his mind, he appeared every inch the seasoned professional for the seventy seconds the fight lasted. He threw a reported 110 punches before lobbing the title-belt over his shoulder and going back to Australia. It was a phenomenal achievement, certainly the most shocking victory in a bantamweight championship fight since Terry McGovern.

He returned to the scene of the crime the following year and repeated the trick, albeit in a more respectful ten rounds.

Now relatively seasoned at 16-0, Carruthers (pictured on the right vs. the aforementioned Bennett) spent the few short months that remained him as a professional fighter beating some of the best in the world. His team tempted American and number five contender Henry Gault out to Australia where Carruthers out-pointed him at an apparent canter; fellow Australian Booby Sinn, ranked eighth, was his inevitable third challenger and once again Carruthers proved too much over the distance, by now adding a cleverness in timing and positioning to his whirlwind attack.

A final fascinating wrinkle to his championship reign presented itself when Chamroen Songkitrat’s promotional team put together a package that tempted Carruthers once again to leave home shores for foreign climes.

Songkitrat, the world’s number two bantamweight contender, had run Robert Cohen desperately close on home soil and his war with Carruthers proved even more dramatic. Such was the profoundness of the downpour that opened upon the ring that footwear became a hindrance rather than a necessity and this fight remains the only championship contest to be conducted barefoot. Carruthers edged home nonetheless.

Just one small measure of the intense drama he wedged into his short career.

#19 – Jeff Chandler (1976-1984)

Like Carruthers, Jeff Chandler was so inexperienced at the highest level as to be denoted green when he took on the undefeated Julian Solis for the bantamweight championship of the world in November of 1980. Having never been fifteen rounds, his capture of that of that title by fourteenth round knockout was even more impressive. Chandler followed it up with another exceptional performance, outpointing the superb Jorge Lujan over fifteen in a torrid affair which he dominated in two distinct phases. Winning rounds inside against the roughhouse Lujan early he re-took control of the fight after a mid-rounds surge from the former champion by using pure boxing. If he could be deemed inexperienced before these contests he was seasoned by the end of them.

Defeating back to back kings, one reigning, one recently former, suggested one of the great bantamweight careers was in the offing; in reality, his best work was behind him. It should be noted though that it was not Chandler’s fault that, for example, Lupe Pintor departed the division for 122lbs. That said, a fight with Alberto Davila would have been big and probably should have been made. This aside, Chandler staged no fewer than eight successful title defenses, including in a rematch against Solis which he won in just seven rounds. Gaby Canizales, Johnny Carter, Eijiro Murata (in a fascinating trilogy, the first of which, a desperate, turgid struggle, was justifiably rendered a draw out in Japan before Chandler won by KO once on either side of the world) and Oscar Muniz are the other men who form the backbone of a really good bantamweight resume.

Chandler was eventually beaten by the kind of pressure he had thrived upon as a younger man, by Richie Sandoval who stopped him in the fifteenth round of their title fight in 1984.

#18 – Sixto Escobar (1930-1940)

Sixto Escobar has become something of a polarizing figure. Depending upon the source you might find him ranked as the single best fighter ever to hail from the fight-mad Puerto Rico, or left languishing outside the top ten. I understand but disagree with both perspectives. The first, I’d suggest, is based upon a rose-tinted view of a bygone era dependent upon oft-repeated rarely proven legends for gas; the latter is about cold hard statistics and brief glances at the sites that house them.

Certainly Escobar’s paper record, a sorrowful 39-23-4, lends itself to doubt but Escobar was far more impressive at bantamweight than above. More, his boxing career blossomed when he began to pursue it full time which was also around the time he went to the U.S.

Between 1934 when he landed on American shores, and 1939 when he made the weight for the final time, Escobar lost precisely two contests at bantamweight, both against world class operators, both avenged. The first of these came against the deadly Lou Salica, who defeated him by the narrowest margin imaginable when the referee (who had scored the fight a draw) declared Salica the winner based upon his supposed superior physical condition at the bell. Escobar hit the canvas in the rematch three months later but clambered up to avenge himself by clear decision, a result he repeated when they met in a rubber match two years later.

The other man to pull the trick at 118lbs was Harry Jeffra. A fighter with a silken jab and quick feet, Jeffra dominated Escobar in a five fight series that stretched from 1936 to 1940, but most of his successes came up at featherweight – in the bantamweight division, Escobar went 1-1 with his nemesis.

The best bantamweight in the world from 1936 until 1939 (that rude interruption by Jeffra aside), Escobar married a quick, inquisitive left to a thumping right, married speed to strength. He rates 5-1 in legitimate title fights and gave up the championship to the scale rather than relinquish it in the ring. That said, he lost a number of non-title fights just above the bantamweight limit; this combined with a hideous paper record exercises some drag on his all-time standing.

#17 – Terry McGovern (1897-1908)

Terry McGovern made weight then sat still, vanished in the day’s newspapers, waiting for the moment when the invisible chain would be removed and the most devastating motion of his era, perhaps any era, would be unbound. A runaway moon of a fighter, he bore himself bodily into even the best opposition unwinding the days and weeks spent in careful preparation for the most hideous assault the ring has ever seen.

One of the greatest fighters ever to have walked the earth, bantamweight was where McGovern immolated his first champion, Pedlar Palmer, “Box o Tricks”, a fighter so excellent that the newspapermen of the time wore their bemusement at McGovern being installed as a favorite over him for their September 1899 title fight in confounded ink. McGovern dismembered him. This terrifying knockout over a world class fighter is where McGovern’s legacy at the poundage rests and he departed the division shortly thereafter.

That, then, explains McGovern’s lowly ranking. One of the greatest ever pound-for-pound, he spread himself too thin and across too many weights to make a top-ten mark at any one of them and bantamweight was where he shook out the last of his learning (he needed three attempts to best the excellent Tim Callahan for example).

His eventually mastery of Callahan and his destruction of Palmer aside, his standout victory was probably over future bantamweight champion Harry Forbes.

Forbes was viewed as “well-nigh invincible” by the time of his 1898 meeting with McGovern. A favorite at the bell, he was undone by as vicious a body attack as can be imagined before McGovern disassociated him from his “air of invincibility” with a right-cross in the fifteenth.

Brutal and brilliant at the poundage, bigger money called him to bigger divisions. What he might have achieved had he remained a bantamweight is a thought in and of itself.

#16 – Lou Salica (1932-1944)

Every time I do one of these lists I come across a fighter who delights and surprises in the depth of his achievement, a fighter who, though known to me at the beginning of the process, was not properly understood by me and whose standing ends in great excess of what I expected it to be.

Lou Salica is that bantamweight and I make no apologies for what is therefore a lengthy entry.

One of fourteen children born in America to Italian immigrants, Salica never received schooling past the age of twelve; for him, it was to be fighting or poverty. A golden gloves victory at 112lbs confirmed that it would be fighting.

I’d suggest that his 1934 victory over the iron-chinned Korean contender Joe Tei Ken was where it all began, but, while he was already scrappy (Salica dropped Ken in the eighth) nobody could have predicted the criminality that Salica was about to perpetrate against the massed ranks of the bantamweight division. The highly ranked “Young” Tommy went next, again out-pointed over ten, this time in something of a surprise, before Speedy Dado put an (unavenged) speed bump in the road. This was understandable; when he out-pointed Indian Quintana in December he had matched his fourth name bantamweight in as many months. Just 23-2-2 he was ushered, probably prematurely, into an alphabet strap contest with the legendary Midget Wolgast.

Wolgast, one of the very greatest flyweights in history, had already defeated a green Salica but that had been the year before. In 1935 the real Salica emerged. He found Wolgast in the sixth, hammered him, dropped him, and took the fight by a shade. He was now ranked the #2 bantamweight contender in the world and would spend an astonishing decade among the top four.

Salica was only champion as seen by California; Baltasar Sangchili was the real champion. When strapholders milk their belt for cash at low risk, it reveals the paper champion for what he is and the “title” he holds for what it is. But Salica, instead, fought the best in the world. Pablo Dano, then among the three best fighters in the world went first; Salica, as was by then almost his habit, outboxed him over ten, separating himself from his game challenger by dropping him in the ninth. Finding a tougher challenge would be hard, but Salica managed it – he outpointed Sixto Escobar in a fight so desperately narrow a pinhead could barely pass between.

Escobar won a pair of rematches, and then Salica won the legitimate championship of the world. Already sporting an entire career under his belt it is arguably the case that he only now got started in earnest. Contenders continued to fall away from him, and then he ran up against a youthful Manuel Ortiz, who appears in the top five of this list. Salica shaded him.

After picking up the vacant lineal championship in a unification fight with Georgie Pace, Salica fought a trilogy with the top contender, Tommy Forte, going 2-1, at which point he began to slip. Successful defenses of his titles followed but the fully fledged Manuel Ortiz was far too much for him and defeated him rather easily in 1942. In the rematch in 1943, Salica suffered the only stoppage loss of his career.

By the end of that career he was known less for scrappy persistence and more for generalship, smarts and good feet. More than the sum of his parts, he was perhaps never a legitimately great bantamweight but he was as special as could be without his being named as such.

Either way, there is no better win resume outside the top ten.

#15 – Chucho Castillo (1962-1975)

Full disclosure: Chucho Castillo is my favorite bantamweight.

But that doesn’t mean he isn’t good for his spot. This blank-faced box-punching genius mixed with a level of competition equal of any who appear on this list.

He served a desperate apprenticeship among the massed banditry of the exceptional and crowded bantamweight ranks in 1960s Mexico, breaking out in 1967 and winning the Mexican bantamweight title. This was no normal national level belt and was held at that time by none other than Jose Medel. Castillo, had now broken onto the world scene, but and continued to duke it out with the best on the Mexican scene even as his assault upon the world championship began.

“He would fight a bull with a fork,” as one promoter put it, and truly, Castillo left no stone unturned in his mission to become the world’s best.

Before he could reach the champion he needed to best the division’s boogeyman, Jesus Pimentel. This, he did, upsetting the odds and wowing a big crowd at the The Forum in Los Angeles on his American debut, handing Pimentel a one-sided “pummeling” said the LA Sun. The great Lionel Rose held the title and, once more at the Forum where he had succeeded in making himself something of a fan favorite, Castillo got his shot.

Ringside reporters were, according to The Press-Courier, split evenly as to the winner; the judges, too, were split, but the heavy end of the decision went to Rose. The LA crowd rioted and two-hundred police officers were dispatched to place them under control. Castillo continued to riot, too. Just four months after his failed title shot he knocked out the all-time great Rafael Herrera, as though he were nothing, in just three rounds. Another title shot, then, was inevitable. To take the championship, all Castillo had to do was defeat perhaps the single best bantamweight ever to have boxed.

Ruben Olivares was riding a thirty fight knockout streak but found himself on the ground looking up after just three rounds against Castillo. Olivares was very far from being a fighter reliant upon his power, however, and he ground down Castillo for the decision.

In the rematch, he dropped Olivares again his right hand, by now perfected, the best in the division’s history for me, and it makes him a technician of the highest order as well as the tank he is reputed to be. Olivares was stopped on a cut, a single point behind on a single card, in the fourteenth round. Castillo was the champion.

Not a great champion, he was one of the greatest contenders in the division’s history.

#14 – Johnny Coulon (1905-1920)

Johnny Coulon emerged out of the old paperweight division to lift the bantamweight title against Frankie Conley in 1911. Issues with counter-claims were terminated in 1912 when he beat Harry Forbes for a second time and the lethal perpetual contender Frankie Burns. Burns was an old foe from his paperweight days and their first title fight was an epic affair of nip-and-tuck decided in a frantic final round. Their rematch was even closer, a draw, at which point Burns gave up on Coulon leaving him to stand astride the division like a colossus.

Coulon’s emergence directly after the collapses of the paperweight title and directly before the emergence of the golden generation of 1920s bantamweights may have rendered him something of a curiosity for the more modern boxing fan but to the old-timers he was catnip. He is one of the few fighters that Charley Rose, Nat Fleischer and Herb Goldman all believe belong in the top ten at bantamweight.

For me, there is an argument. Coulon’s title reign runs through thirteen defenses before he lost it to the all-time great Kid Williams in 1912. That is a huge number. The flip side of this coin is that Coulon boxed a lot of no contests, that is, fights where he had to lose by knockout to be separated from the championship as no official decision was being rendered, and he lost two of them according to ringsiders.

Now, that isn’t as disastrous for his legacy as it sounds. In those situations, everyone involved knows what is at risk and how the fight is working. Nobody is being “cheated”. Coulon also staged “real” defenses where decisions could be rendered, but in the no contests he knew, as champion, that getting to the final bell was his only real job. So did his opponents.

For this reason, his “losing” a six-round no decision to a middling fighter was of no real consequence in his own era, and when he “lost” a ten round fight to Kid Williams he rewarded him with a legitimate title shot. Williams stopped him in three, ending his title reign.

Perhaps a sliver ahead of his time in the way he used his jab to set opponents up for bodywork, Coulon comes across as a smart, durable, quick-handed fighter who might have reigned in any era.

#13 – Joe Lynch (1915-1926)

Joe Lynch is our first introduction to a true monster of a true golden age of the bantamweights, a series of champions and contenders that made for the best division in all of boxing in and around the 1920s.

Despite the consistently high level of competition, Lynch was champion of the world not once, but twice, first taking the title from the immortal Pete Herman during Christmas of 1920 and then from the capable but less deadly Johnny Buff in the summer off 1922. His 1920 pass at the world championship may have been his best performance. Herman had suffered a ragged year and was likely past his absolute peak but he still had some exceptional nights before him. Tall, rangy, slender, Lynch was blessed with perhaps the best one-two in an era stuffed with technicians. An underdog, he landed enough of these punches to win as many as ten of the fifteen rounds.

Lynch, who struggled at the weight, nevertheless spent around a decade at bantamweight and used similar tactics to build one of the single best win resumes in the history of the division. He defeated Frankie Burns, Memphis Pal Moore, Abe Goldstein, Charles LeDoux, Young Montreal, Joe Burman, Jack Wolfe and many more noted men of an era as stacked as any that has ever existed at any weight.

Taken in tandem with two stints as world champion it has resulted in his being ranked at #4 at the weight by Nat Fleischer, and #11 by the IBRO; here, he appears further down.

Why?

In short, it is because while he defeated numerous excellent bantamweights, he only rarely won a series with one. The great bantamweights of the 1910s and 20s fought each other over and over again, and an impressive 1-0-1 tally against Kid Williams aside, Lynch did not impress. He lost three of five to Pete Herman (including a rematch to that wonderful title-winning effort), went 3-4-2 with Memphis Pal Moore (whom he tends to rank in front of on “classic” bantamweight lists), dropped two of a trilogy to Frankie Burns and split a pair with Abe Goldstein. Luck went for and against him across these wonderful series – but he was never the proven man.

He was able to beat some lesser fighters in extended series, but here is a fact where Lynch is concerned: great fighters usually got the better of him in protracted series.

A great bantamweight – a bantamweight capable of beating literally any 118lb fighter who ever has lived – but just a little bit shy of the ten.

#12 – Bud Taylor (1920-1931)

Bud Taylor was never the lineal champion at bantamweight, but he did prove himself the inherent superior of two of the major kings of that period in Charley Goldstein and Charley Phil Rosenberg.

Taylor crushed an admittedly pre-prime Rosenberg in 1923, two years before he came to the title, but his superiority over Abe Goldstein was much more marked. Taylor defeated him three times between 1925 and 1927, each time by points, and on the first two occasions having a decided advantage. Taylor was better than Goldstein and better than Rosenberg.

So no lineal title, but there was a strap, the vacant NBA strap, and to obtain it, Taylor had to overcome no lesser a personage than Tony Canzoneri. Canzoneri, one of the very best ever to box, did not achieve excellence at bantamweight in the same way he did further up the scale and Taylor was the reason. The two met for the vacant NBA title in March of 1927; Taylor dominated – Canzoneri did what Canzoneri almost always did and pulled off a spectacular rally in the tenth and final round to rescue a draw. Between that contest and their June rematch, Taylor found time to make four separate engagements, keeping up his breakneck schedule, remarkable even for the time, despite title honors looming. Goldstein and the ranked Young Nationalista were included among his victims.

He appeared the fresher man in the rematch, however. Taylor had won spells of their first fight with pressure and in the second he was relentless; this was Taylor distilled. An aggressive juggernaut who surrounded foes with leather and bad intentions.

He was also beloved of old time historians who, again, consistently ranked him higher than I have here. Nat Fleischer had him #5 all time; Charley Rose #9. I understand why. He would fight anyone and he beat most of them – but not all of them. In four pokes at Memphis Pal Moore he could not get the better of him once; more disturbingly he dropped a series with the undersized (though brilliant) Pancho Villa.

#11 – Rafael Herrera (1963-1986)

In 1969, Chucho Castillo stopped Rafel Herrera in three; in 1971 Herrera secured the rematch and avenged it but in the narrowest of narrow decisions. As fine a fight as was ever contested at bantamweight was what these two engaged in at the Forum and when they went to war in the twelfth, for a second time after the desperate and vicious fourth, it was for all the marbles. Herrera got home by a split decision.

Castillo and Herrera were contemporaries and for me they have always come as a pair. Technically wonderful, craftsmen both, as tough as Mexican bantamweights should be, as drilled and both, briefly, were champions. They met twice, and it was Castillo who got the better of that pair, winning by knockout where Herrera squeaked home in an arguable decision, but they are separated by more pressing matters than their own rivalry.

In 1972 Herrera met Ruben Olivares for the world title. Olivares had been beaten in 1970 by Castillo but since then had reclaimed his title in a rematch and blasted out several excellent fighters, including the murderous Jesus Pimentel. Herrera harried and harassed him, pressuring him with jabs and a disciplined guard, countering to the body, he systematically deconstructed him. In the course of the eighth he put two right hands through the champion then, later, caught him with an almost incidental looking hook; Olivares went down face first and rose at eleven. Herrera then apologized to the legend he had mortalized.

Herrera lost the championship in his very first defense, against Enrique Pinder but he picked up another piece of the title and rounded off an absolutely beautiful resume in style. In addition to Olivares and Castillo he defeated Romeo Anaya, the wonderful ex-flyweight Venice Borkhorsor, Rodolfo Martinez, all of whom were among the very best bantamweights in the world when he took them. Add supplementary wins over the likes of Octavio Gomez and he crafted a resume nearly almost good enough see him named among the ten greatest bantamweights in history.

Almost, but not quite.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers