Argentina

The Fifty Greatest Bantamweights of All Time: Part Five, 10-1

There was really no right answer. Each man had a strong case. It was only in putting each of them through the wringer that I came out with an answer that satisfied me

Organizing the top three at lightweight was as difficult a task as I have undertaken in finalizing a divisional top ten. There was really no right answer. Each man had a strong case. It was only in putting each of them through the wringer that I came out with an answer that satisfied me. That is, I tried to undermine each man’s argument to uncover whose was the most resistant.

This is most effective when organizing lower tiers. It’s rarely needed up here where the air is clean and the fighters are gods. But I ran in to trouble again at bantamweight. It meant looking over three of the most splendid fighters in history more critically than I felt comfortable with; the result is a more concentrated eye but a less loving brush.

A tiny minority of you won’t have scrolled down to catch those three names upon reading that, so I will not indulge in spoilers here. What I will say is that I was very satisfied with this list, both at this end and the back end. I reviewed it last night and the only thing I would change would be to introduce old-timer Al Shubert at #50. That aside, I’m content and ready (as I’ll ever be) to tackle the flyweights.

As for the bantamweights, I have many disagreements with the divisional lists from history. All of the men writing them saw more of these bantamweights than me and some of them had a better understanding of the sport than me but I will say this as a sign off: I’m satisfied that no bantamweight list of this length has ever been so thoroughly researched as this one.

Hopefully then, this has informed the top ten.

This is how I have them:

#10 – Carlos Zarate (1970-1988)

Carlos Zarate’s story is told in blood and punches.

My favorites landed – detonated is likely a better word – in 1975. Zarate was just another contender then, for all that he was one with violence painted upon every canvas he ever stepped upon, thirty three fights and thirty-two knockouts in his terrible wake; his opponent, perhaps was not even a contender.

A gatekeeper marked with the name Orlando Amores, he troubled Zarate early, not unusual, many lesser men tested him while he sought them, but when he found them…

In round three Zarate countered an increasingly frenetic Amores to the ropes and parked two neat uppercuts followed by a neat hook upon his opponent’s chin. They were not violent punches – they were hardly even flamboyant. They were thrown a little like a drunk emptying two full ashtrays into his garden. But Amores was gone, capable only of rolling onto his stomach, face pressed to the canvas, gloves either side of his head as though in devout prayer, heaving in oxygen.

In 1976 Zarate deployed said violence against the superb Rodolfo Martinez, cracking him to the canvas in the fifth and breaking him down with those extraordinary, long, luxurious punches, finally terminating his resistance with a right uppercut in the ninth.

The tough Italian Paul Ferreri lasted a little longer before Zarate opened up his face for him. The unbeaten Alonso Zamora, the world’s other outstanding bantamweight, lasted only four before being blasted into the same netherworld Amores had been sent to. When his corner threw in the towel it landed across their fighter’s eyes and he raised himself, more defeated barfly than professional fighter.

Even Alberto Davila, one of the toughest bantamweights ever to live, could not survive him, succumbing in eight.

Zarate’s punches changed men. He introduced them, briefly, to their own mortality.

All that said, despite a 10-1 record in title fights (and the “1” a questionable loss to Lupe Pintor) his resume is not as glittering as that found in the rest of the top ten. Zarate’s fearsome reputation as a puncher and a fighter has preceded him here as it does elsewhere. In short, he is arguably and fittingly punching above his weight. I would suggest that by the strictest interpretation of my criteria, Zarate belongs at #11, below Rafael Herrera.

But on the back of more questionable phrases like “head to head” he squeezes into the Ten.

Other Top Fifty Bantamweights Defeated: Rodolfo Martinez (36), Alfonso Zamora (25)

#09 – Panama Al Brown (1922-1942)

The legendary “Panama” Al Brown towered over most of his opposition at around 5’10, an enormous height for a bantamweight of his era – tall even today – but not the oft reported 6’0 of lore. Loose, fast, Brown used his gifts to dominate from the outside, a booming right hand to the torso among his best punches; but he was also a world class improviser. Some years before the prime of one Kid Gavilan he was throwing something that looked very much like a bolo punch. Despite his skills at range he had mastered the art of infighting and of tactical fouling on the referee’s blindside. It takes less than an hour to review the Brown footage that appears on video hosting sights around the internet and doing so is an illuminating experience.

His great talent added up to one of the longest title reigns in bantamweight history and a decade ranked among the best bantamweights in the world. Unfortunately he did not defend his title with great frequency, nor was he consistent in non-title fights, dropping decisions to Speedy Dado and Newsboy Brown.

Nor did he have the competition to match the resumes of those great champions who made their bones in the 1920s but he seemed, in his own time, irresistible.

Other top fifty bantamweights defeated: Pete Sanstol (43).

#08 – Kid Williams (1910-1929)

Kid Williams was a hideous mix of pressure and violence, one of bantamweight’s great ring terrorists. He thrashed at the opposition with a belief born of certitude, certitude which itself was born of some other dark sense – perhaps a notion that he was doing exactly what he was born to do.

Williams’ 1912 run at the title, held by Johnny Coulon, was terrifying. He fought 19 times between January and November losing exactly one contest, to Johnny Solzberg, in a razor-thin decision that reads like it could have gone either way. Williams beat up seven more professionals then re-matched Solzberg and kept the pressure on to stop him in seven. Williams was not one for loose ends.

He was unsuccessful in his first title bid because he failed to knock Coulon out in a no-decision, but he dominated him and left little doubt as to the true identity of the world’s best bantamweight.

“Williams’s great strength told the tale.” reported the New York Sun. “He stood up under Coulon’s clean cut punches without breaking ground or wincing…[Coulon] received the hardest beating of his career.”

To his eternal credit, Coulon offered Williams a rematch which Williams immediately accepted. Coulon, although true to his word, made Williams wait. So Williams went on a twenty-one fight maraud through the division, defeating made men like Eddie Campi and Charles LeDoux. He did not lose a single contest. He had peaked, a perfect animal and when he finally got Coulon into the ring in June of 1914, he tore him to pieces, shredded him in three rounds, inflicting upon him the first stoppage loss of his career.

Twenty days later he thrashed Pete Herman, one of the greatest bantamweights to ever live, winning as many as eight of the ten rounds and placing Herman “in distress” in the ninth round.

Williams’ time as true title holder was not that impressive. He boxed only two draws and a (generally ignored) disqualification loss, but the two draws were epic twenty round contests with no lesser figures than Frankie Burns and Herman. It was Herman who then took the title from him in 1917.

I would suggest that during at least a portion of this spell, Williams was as un-boxable as any bantamweight swarmer in history. In his way he was as deadly and untameable as Terry McGovern. Those two only missed one another by a few years; it was likely best for both of them.

Other Top Fifty Bantamweights Defeated: Abe Goldstein (37), Johnny Coulon (15), Pete Herman (Top Ten).

#07 – Memphis Pal Moore (1913-1930)

Pal Moore was never the bantamweight champion of the world and is the highest ranked bantamweight never to have succeeded in obtaining that honor.

He did run a “claim” for a while during the first reign of Pete Herman, although it pretty much petered out as the level of Herman’s dominance became apparent; but it is not for a paper title that Moore brushes the top ten, rather for the way he terrorized multiple legitimate champions over a ten year period, winning epic series with each of them. This is worth repeating: Memphis Pal Moore triumphed in extended rivalries with Joe Lynch, Bud Taylor and Pete Herman.

He tackled Herman twice, first in eight rounds back in Memphis in 1915 in what seemed to be a routine win. In 1919 – by which time Herman was the champion of the world – the two met once more over the shorter distance of eight rounds in a non-title fight. Moore was the decided winner, taking as many as six of the eight rounds, out-working and out-boxing the reigning champion of the world. No title shot materialized, perhaps with good reason.

Joe Lynch was the champion of the world in two spells between 1920 and 1921, then between 1922 and 1924; during both spells, Lynch ran into Moore. Before their May 1921 contest, Lynch declared himself as fit as he had ever been in his career. Despite his confidence, he weighed in wearing clothes and shoes in order that he would be outside the weight class and so unable to defend his title. His caution was more merited than his confidence. Despite a wobble in the twelfth, Moore finished the final round “way ahead” of the champion.

They fought a rematch after Lynch had lost and re-won the title but on this occasion Lynch got the better of Moore. In fact, the two fought one of the most epic and under-celebrated series in boxing history, meeting on no fewer than ten occasions; Moore, by most ringside accounts, came out with the slenderest of edges over the lineal champion, going 4-3-3.

Bud Taylor tussled with Moore on four separate occasions, all in no decision bouts and probably before his prime, but appears never once to have taken the best of their confrontations. Two wins for Moore and two draws are generally how their fights are remembered.

He also defeated Kid Williams on the one occasion that the two met – yes, Moore is generally believed to have bettered him, yes, it was in a no-decision bout while Kid Williams was the reigning champion of the world, and no, he did not receive a title shot.

Moore went 9-5-3 against this murderers’ row of championship competition in a golden age of the division. I would suggest this means three things: first, that he is among the very best fighters ever to have been without a world championship; second, that he was, late in 1918 and early in 1919, probably the best fighter on the planet; and finally that, despite rarely being placed there, he is a near lock as one of the ten greatest bantamweights in history.

Other Top Fifty Bantamweights Defeated: Joe Lynch (13), Bud Taylor (12), Kid Williams (Top Ten), Pete Herman (Top Ten)

#06 – Lionel Rose (1964-1976)

Lionel Rose is a part of the royal bloodline at bantamweight that stretches from 1961 to 1970 and encompasses the title reign of Eder Jofre then Fighting Harada, who lost the crown to Rose, who lost it to Ruben Olivares. All four of these men appear in this Top Ten. I think it unlikely that four such talented fighters ever passed any title hand to hand in this way.

Perhaps a little unfairly I would identify Rose as the weak link among these four great champions; but this is a little like identifying Ringo as the weakest member of The Beatles. It’s better being the worst musician in the greatest band ever to have played than the best musician in your mother’s basement.

More, Rose did some damage in this clash of kings, traveling to Japan in 1968 to meet the man who had defeated Eder Jofre, Fighting Harada. The referee docked Rose for a non-existent foul and warned him repeatedly for hitting with the open part of the glove. It didn’t matter. Rose was as beautiful that night as any bantamweight pugilist ever has been. He won rounds on his toes, he threw uppercuts to the heart, he threw hooks to the ribs, he led with the right, he moved from a left-handed clinic to a booming overhand right which even flashed Harada to the canvas in the ninth.

I saw it wide and even though the judges had it desperately narrow they had it to the right man, new bantamweight champion of the world Lionel Rose.

I have never seen Rose quite as special as he was against Harada, which is one of the most complete performances in ring history for my money, but he was good enough to turn away numerous top contenders including Tukao Sukari and, in desperately close but justifiable distance fights, Chucho Castillo and Alan Rudkin.

It took a series of desperate struggles with the weight and a fighter as good as Ruben Olivares to separate him from the title.

Other top fifty bantamweights defeated: Alan Rudkin (40), Jose Medel (28), Chucho Castillo (15), Fighting Harada (Top Ten).

#05 – Pete Herman (1912-1922)

Pete “Kid” Herman was The Don of the second deepest bantamweight division in history, the boss of the best division in boxing in that era, atop a pile of fighters so deep and wide that even Ruben Olivares or Eder Jofre would have had their hands full.

Even Herman, who ruled in two spells, first between 1917 and 1920 and then briefly once more in 1921, couldn’t sit atop such a pile unmolested, and he seems to have come off worse in a trilogy with Frankie Burns, for example. But his superb body punching and a skill at infighting which may have been unparalleled at the poundage, worked concurrently to help him negotiate one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the sport’s history with great success. Kid Williams came off worse. So did the great champion Johnny Coulon as did Herman’s polar opposite in style, Joe Lynch, who was edged out in the course of an epic five-fight series.

Herman’s beginning in boxing was inauspicious, as he struggle desperately to overcome local New Orleans rival Johnny Fisse; it took him three years and seven attempts to get it right. After learning a last lesson from the deadly lightweight Lew Tendler in 1916, Herman was ready for the title, prizing it from the grasp of no less a figure than Kid Williams and holding it until Joe Lynch separated him from it in 1920. Herman was well beaten in that fight, seemingly nervous and struggling for the majority of the rounds to find a way in, so his victory in their 1921 rematch is perhaps my favorite Herman performance. Lynch won one round according to the Morning Oregonian, a great bantamweight totally and utterly outclassed by one of genius.

There is competition for the slot of best Pete Herman performance, however. The seventeenth round knockout of the immortal Jimmy Wilde? His almost unbelievable three round dispatch of the wonderful Johnny Coulon? His title winning victory Kid Williams?

Few careers can boast such treasure.

Other top fifty bantamweights defeated: Jimmy Wilde (35), Frankie Burns (21), Johnny Coulon (14), Joe Lynch (13), Kid Williams (Top Ten)

#04 – Fighting Harada (1960-1970)

A decade of mayhem and madness is what this ghost-wave of a pressure fighter wrought upon the flyweight and bantamweight divisions, but it was at bantamweight that Fighting Harada joined the true ring immortals.

Jose Medel defeated him in 1963 but between that time and his title-defeat to Lionel Rose in 1968 he went 19-0 and 5-0 in bantamweight title fights.

In terms of quality per-defense, this may be the single greatest meaningful title reign in the history of the division.

First, Harada had to take the championship from Eder Jofre. It was likely there would be a man to do that eventually, I suppose, but that man was always going to be an extraordinary fighter turning in an extraordinary performance, and so it was. Harada demonstrated the perfect execution of the swarming style and then claimed ring center in the final third, even surviving a near-disaster when Jofre came for him late. It was a complete title-winning performance that I scored much wider than the judges and press in attendance, who had Harada ahead by a sliver.

In his first defense, Harada met Alan Rudkin in what seemed to me a much closer fight with every round desperately contested between two world-class operators. Rudkin boxed or punched his way into contention in nearly every single round; he was inspired and I suspect that the bantamweights who would have beaten him that night who are ranked outside the top twenty are few. Harada demonstrated iron will and an impermeable spirit, lashing back over and over again to take the decision.

Then Harada rematched Jofre, reported that he found the second fight easier than the first, and moved on.

Long overdue a soft defense, Harada instead re-matched Medel, the last man to have beaten him in a torrid fight that Harada named his most difficult title fight; the dazzling speed and quick elegance of Bernardo Carraballo may have overhauled Medel’s claim later that same year.

By 1968 Harada’s battles with the weight had become legendary. He had his title ripped from him by Lionel Rose that year and left the division for a tilt at the featherweight title. He left behind him an astonishing reign and a pair of victories in his defeats of Jofre as wonderful as any held by anyone at any poundage.

Other top fifty bantamweights defeated: Bernaro Carraballo (48), Alan Rudkin (40), Jose Medel (28), Eder Jofre (Top Ten).

#03 – Eder Jofre (1957-1976)

Shocked? I am too, a little.

Eder Jofre is generally held to be the greatest bantamweight who has ever lived. He was ranked number one in the IBRO poll; if you google “top ten bantamweights” you’re as likely to see him atop the list as not and those that replace him are an even spread. He gets the nod ahead of Manuel Ortiz and he gets the nod ahead of Ruben Olivares more often than not.

He boxed around half the defenses that Ortiz did. The fighters he beat were not as good as the ones Olivares beat.

So the argument for Jofre, essentially, is consistency and how he looks on film.

I am throwing out the second part of this argument up front. There is no question of his looking better than Ruben Olivares on film. Olivares looks no better than he, that is true, but these two are just about as good as it gets. Neither looks better than the other. The argument is more difficult as it pertains to Manuel Ortiz, but footage of Ortiz is limited. I would concede that from what we can see, Jofre has a slender edge over Ortiz here.

Jofre was arguably more consistent than both. Between 1957 when he turned professional and 1965 when Fighting Harada caught up with him, Jofre did 46-0-3, an incredible run and a fact that, for me, is the primary reason he should always be considered for the #1 slot.

However, Jofre won around half the world championship fights that Ortiz won. If consistency is the most major argument in seeing Jofre above Olivares, what about the counter-argument, that Ortiz was more consistent in fights that truly mattered? And what of the fact that Olivares has higher raw numbers than Jofre by the time of each man’s first loss?

The picture is confused further by this fact: Ortiz never ran into a possessed demon like Harada, which Jofre did.

That, in turn, makes Jofre vulnerable to the contrary argument, specifically that Olivares was the main man in the deepest bantamweight division in history. Jofre cannot match Olivares for quality of competition met or bested.

In summary: there is nothing at all wrong with ranking Jofre as the greatest bantamweight in history. He is a solid selection under almost any criteria and he is but a hair’s breadth from that position here. He was a wonderful fighter. Probably you can count the men who were flat out better than him in all of history on your fingers. But he is not my choice for the number one position here.

The top three are really 1a through to 1c; that said, Jofre is 1c, and I stand by that.

Other top fifty bantamweights defeated: Bernardo Caraballo (48), Jose Medel (28).

#02 – Manuel Ortiz (1938-1955)

A Mexican-American who dominated a weight division during perhaps the most fondly remembered era in American history, the 1940s, Manuel Ortiz remains a shade in history when compared to the other contenders for the number one spot at bantamweight.

For that is what he is. The statistics associated with the career of Manuel Ortiz are astonishing.

He reigned in nine calendar years in two spells between 1942 and 1950. His record in title fights is twenty-one and two. He is one of the few men on this list to have conquered so many ranked contenders as to require double digits for accurate depiction. He beat the best fighter in the world excepting himself on multiple occasions.

In more than 130 fights he was stopped just once, on cuts. He himself dished out more than fifty stoppages despite a dearth of power, his excellence in dissecting his opposition often resulting in their crumbling.

He took the title from the borderline all-time great bantamweight Lou Salica in 1942. It was easy. I haven’t seen a report that gives Salica more than three of the fifteen rounds.

I also haven’t seen the fight. Key fights belonging to Manuel Ortiz are tough to come by in a way I just can’t explain. It’s heartbreaking because few were so brilliant.

You can see his third meeting with Luis Castillo, which is important, because that was a part of perhaps the best bantamweight run in history. Between his revenge win over Tony Olivera in 1942 and the summer of 1946, he lost just once, up at featherweight, to a fighter named Willie Pep. Title defenses abounded against a huge variety of styles and Ortiz turned them all away, often with ease.

When he finally lost his title in 1947 in a strangely lackluster performance against Harold Dade, he dusted himself off, went back to camp ,and reclaimed it, narrowly but clearly, in a rematch. If you could bottle Ortiz’s essence you would have yourself the stuff of not just champions but, for me, the defining bantamweight champion.

Only a monster keeps him from the number one spot, but his presence there would be fully justifiable.

Other top fifty bantamweights defeated: Lou Salica (16)

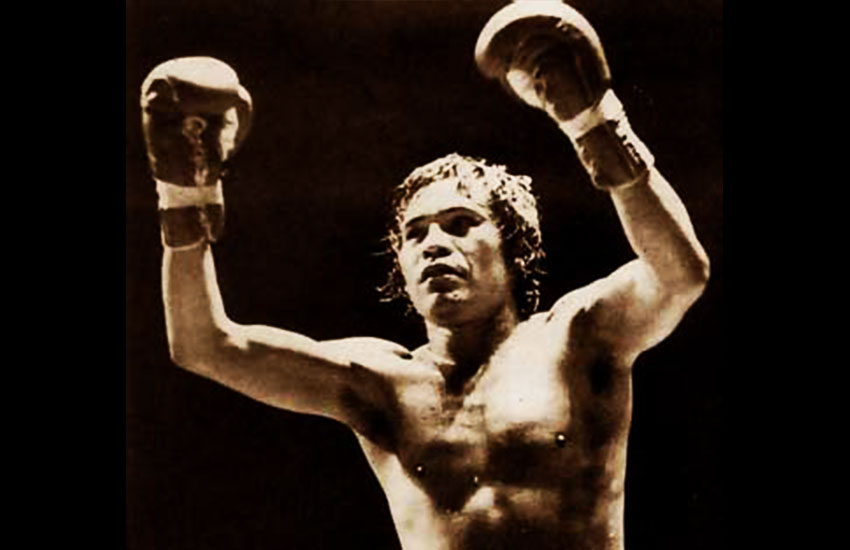

#01 – Ruben Olivares (1965-1988)

Ruben Olivares (pictured) was an absolute doomsday machine of a fighter, a knockout artist and a genius both. He did not so much knock opponents out as immolate them, vaporize them, vanish them from competition and their own senses. A strange separation seemed to occur within the fighter when he landed his best; knockout victories over Jose Bisbal and Efren Torres, especially, instill within me the alarming sense that we are watching a man having his soul removed from his body but that the body has not yet been fully alerted. The slow collapse of Jim Braddock by Joe Louis has always been seen as something special; I think Olivares did this kind of thing almost routinely.

But it is not for his knockouts of the likes of Jose Bisbal and Efren Torres that Olivares has been ensconced in the number one slot. It is for the years he dominated the single most destructive division in history at the poundage. Olivares ruled in 1969 and 1970 before Chucho Castillo unseated him at the second time of asking. Olivares re-took his title in the rematch and ruled once more between 1971 and 1972, at which time Rafael Herrera took over. Olivares got two bites at Herrera and despite the fact that he was, by then, tight at the weight, his failure to defeat his nemesis is the one real knock on his bantamweight legacy.

What a legacy it is. Like Fighting Harada, Olivares fought title fights only of the very highest quality but he managed more than the brilliant Japanese. In quality, he falls short only by the absence on his championship resume of a figure as monumental as Eder Jofre. Olivares, on the other hand, was as monumental as Jofre.

He took the championship from one of the greatest bantamweights ever to have lived in Lionel Rose, destroying him almost as easily as Brisbal or Torres, smashing him out in five. His first defense was against Alan Rudkin, who had been in desperately close fights with both Harada and Rose. Olivares blasted him to the canvas three times in two rounds, dusting him off like a journeyman. His second defense was against perhaps the greatest bantamweight contender in history, Chucho Castillo, whom he ripped and harried and battered to a clear decision defeat. After swapping the title with Chucho, Olivares added number four contender Kazuyoshi Kanazawa and all-time great puncher Jesus Pimentel. His record, which up until recently had stood at 61-0-1 now read 68-1-1. Olivares was atop a pile of bantams as brilliant as had ever been assembled for the second time.

When the punches failed, Olivares morphed into one of the greatest ring generals in history. His generalship failed him only once. Few such skilled boxers held as much power. Few power punchers have boxed with such skill.

There are two other names that could have rocked the top spot, and in earlier drafts they did. Olivares, though, is named my choice as the greatest ever bantamweight, albeit by the slightest of margins.

Other top fifty bantamweights defeated: Jesus Pimental (49), Alan Rudkin (40), Chucho Castillo (15), Lionel Rose (Top Ten).

For those of you who have taken the time to read this series from first to last, I thank you.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds