Featured Articles

Thomas Hauser and Others Remember Dave Wolf at 75

This week marks a bittersweet milestone. Dave Wolf would have been 75 years old on August 24.

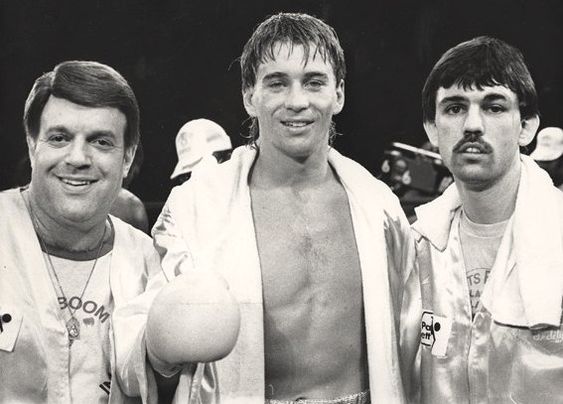

Dave died ten years ago, on December 23, 2008. As I wrote at the time, he was passive-aggressive, anti-social, and one of the smartest people I’ve ever met. He also did as good a job of managing Ray Mancini as any manager ever did for a fighter and performed managerial magic on other occasions for the likes of Donny Lalonde, Duane Bobick, Lonnie Bradley, Ed “Too Tall” Jones, and Donnie Poole.

The legendary Jimmy Cannon once wrote, “The fight manager wouldn’t defend his mother. He has been a coward in all the important matters of his life. He has cheated many people but he describes himself as a legitimate guy at every opportunity.”

Dave was the antithesis of that. His first question was always “What’s best for the fighter?” rather than “What’s best for me?”

He had as full an appreciation of boxing and its traditions as any person I’ve known. Beneath his gruff exterior, there was a warmth about him that led to his being embraced by those who knew him best. And he’s assured a slice of immortality because of his accomplishments in the sweet science and as the author of Foul: The Connie Hawkins Story, one of the best books ever written about basketball.

Recently, I asked some people who knew him what comes to mind when they think about him today.

Jon Wolf was Dave’s brother.

Gina Andriolo met Dave in the 1970s while she was working for a small newspaper in Brooklyn. Later, she represented Dave as his attorney. Eight years after they met, they were married. They separated after four years of marriage.

Toby Falk and Dave were high school sweethearts. Decades later, they reunited and lived together in Dave’s apartment on the upper west side of Manhattan from 1989 until his death in 2008.

Teddy Atlas trained two of Dave’s fighters, Donny Lalonde and Donnie Poole.

Ray Mancini was Dave’s signature fighter.

Ray Leonard fought Donny Lalonde, another of Dave’s fighters.

Seth Abraham and Lou DiBella knew Dave in their capacity as executives at HBO.

Bruce Trampler was a matchmaker for Bob Arum during Ray Mancini’s glory years with the promoter.

Promoters Russell Peltz and Artie Pelullo worked with Dave on several fights.

Ron Katz and Don Majeski have been matchmakers, advisers, and jacks-of-all trades in boxing for decades.

Al Bernstein, Larry Merchant and Jerry Izenberg knew Dave through their roles in the media.

Harold Lederman (HBO’s “unofficial ringside judge”) was judging fights officially when Dave was in his prime as a manager.

Randy Gordon was editor of The Ring when Ray Mancini was at his peak as a fighter.

Mark Kriegel wrote what is widely regarded as the definitive biography of Ray Mancini.

Craig Hamilton managed several fighters and is the foremost boxing memorabilia dealer in the United States. He dealt extensively with Dave in the latter capacity and helped Dave’s family liquidate his memorabilia collection after Dave’s death.

Some of their memories follow:

Jon Wolf: “My father had severe back problems that limited his mobility. Dave was six years older than I was, so when I was a boy, he played the role of father in teaching me to do things like riding a bike and playing baseball. He took me to the NFL championship game between the New York Giants and Green Bay Packers at Yankee Stadium when I was twelve years old. It was freezing cold, and Dave kept missing parts of the game to get up from our seats and go get hot chocolate for me to keep me warm. I played basketball in high school. Dave was in journalism school at Columbia by then and came to all my games. He’d sit in the stands and shout instructions. There were times when it was like he was coaching the game.”

Gina Andriolo: “I was young when I met Dave, and I was very impressed. Right away, I could see he was one of the smartest people I’d ever known. He was very intense in his interaction with people. He could be brusque and combative. He always let people know where they stood with him. He liked being alone. And he loved sports; all sports, not just boxing. Dave could watch curling on TV and be happy.”

Toby Falk: “Dave was creative, intellectually curious, very intense, stubborn, determined. He was a private person, not at all social. He had no interest in talking with most people. Every now and then, he’d go to an opening at the Museum of Modern Art with me because he loved me, but it was a chore for him. If he bonded with you, he really liked you. But there weren’t many people who fit into that category. He’d stay up into the wee small hours of the morning watching old fights on television. But it wasn’t just boxing. It was all sports. His idea of a beautiful summer Sunday was to sit inside and watch a baseball game on television.”

Jerry Izenberg: “He was a very good writer. That’s what stands out in my mind. People remember that he wrote Foul, which was a very good book. But he also wrote some very good magazine articles.”

Al Bernstein: “Dave wrote one of my favorite books and one of the best sports books ever written. It was about Connie Hawkins, who’d been banned from playing in the NBA, and it broke new ground for what a sports book should be. Beyond that, Dave did what managers are supposed to do. He worked hard and maximized every opportunity for his fighters. I liked him a lot.”

Bruce Trampler: “I’ve never dealt with anyone who did his homework the way Dave did. He was one of the most conscientious, dedicated, well-prepared managers ever. I spent hours on the phone with him going through every detail of every fight again and again. Every conversation turned into a cross-examination. He was always asking questions and taking notes. He was painstaking in his preparation at every level. I give him the highest marks in every category that has anything to do with managing a fighter. He could be an annoying bastard and he was a complete pain-in-the-ass to deal with. But he was doing his job as he saw it, and he was one of the greatest managers ever.”

Ray Mancini: “Nobody – I mean, nobody – paid more attention to details than Dave. When I fought Alexis Arguello, Dave got Top Rank to agree that I’m going to leave the dressing room after the national anthem ends. If Arguello isn’t in the ring and the fight doesn’t start seven minutes after I’m in the ring, I’m leaving and Arguello has to wait for me to come back. That’s fine with me because, as a fighter, I don’t want to stand in the ring and get cold waiting for the fight to start. And everyone knew that Dave was crazy enough to take me out of the ring if Arguello was late. I loved it. I fought Ernesto Espana outdoors in a football stadium in Warren, Ohio. The day before the fight, Dave went to the stadium and stood in the ring at the same time of day the fight would start. Then he said, “Okay, this will be Ray’s corner and this will be Espana’s corner.’ He was making sure I had as much shade in my corner as possible and Espana was facing the sun. As a fighter, you love stuff like that.”

Lou DiBella: “He was a stand-up guy. For a guy without much charm, he was colorful in his own way. He was a guy who knew how to sit back and watch and figure out what was going on. He understood the strengths and weaknesses of his fighters. And unlike too many managers in this miserable business, he recognized that he had a fiduciary duty to his fighters and acted like it. There were never any side deals that the fighter didn’t know about.”

Mark Kriegel: “Dave was trained as a journalist. He was a story-teller, and that’s part of what a great manager does. He understood why Ray Mancini mattered, and he was able to tell the story in a way that people understood. He went from being a journalist to a producer, and he was great at it. I never met him, but I can’t think of another manager I would have liked to have met more.”

Randy Gordon: “Dave would come up to my offce at The Ring to look at old Ring magazines. This was before the Internet and Ebay, so it wasn’t easy to find them. He’d sit there and read, and then we’d talk about what he’d read. I learned a lot of my boxing history from those conversations. Some people thought Dave was on the weird side, different, strange, whatever word you want to use. But I enjoyed him as a fight guy, and I knew how much he cared about his fighters. He poured his heart into them.”

Don Majeski: “It’s easy to move a great fighter. Some fighters are so great that you don’t really have to manage. You just point them in the right direction and ask for more money. A great manager gets the most out of the least. Dave got people to treat .200 hitters like they were .300 hitters and .300 hitters like they hit .350. He made Ray Mancini, who was good but not great, into an iconic fighter. Bob [Arum] gave Ray the exposure, but it was Dave who gave Bob the product. He made millions of dollars for Donny Lalonde, who was an okay fighter. He got Ed “Too Tall” Jones onto CBS. He always looked after his guys. He never wanted one of his fighters to be an opponent. He was one hundred percent for his fighters. He was a great boxing guy.”

Craig Hamilton: “Ray Mancini was a likable white Italian-American fighter with a crowd-pleasing style. Any competent manager could have made good money with Ray, although probably not as much as Dave did. But look at the job Dave did for Lonnie Bradley. Lonnie was a black kid out of Harlem who was a competent fighter with a quiet personality. Dave maneuvered him to a winnable title fight [for the WBO middleweight belt against 13-and-6 David Mendez] and then got him a half-dozen title defenses against guys who weren’t very good.”

Teddy Atlas: “There were some things Dave did that I took issue with in terms of our relationship. But I recognized his gifts and his ability to move a fighter. He was a smart guy. He knew how to play the game with the sanctioning organizations and was willing to play it. He loved playing the game. I think he enjoyed the maneuvering and getting to the kill more than the success of it. And he made money for his fighters. A fighter can be successful in the ring and not make a lot of money. Dave made good money for the fighters he managed. His talent was to take a fighter who was okay and make it appear to the world that the fighter was better than he was, maybe even great. He knew how to build a fighter and capitalize on it when the fighter won. He was a master at developing a storyline for his fighters and having it resonate with the press. He was difficult; some would say crazy. But he did the job for his fighters.”

Ray Mancini: “Dave was a control freak. That was his thing. He was doing it for me, but he wanted total control and we had our battles. Sometimes I had to tell him, ‘You work for me. I’m the fighter.’ Then he’d get hurt and sulk and say things like, ‘I guess you don’t need me anymore.’ If he got a bug up his ass about something, he wouldn’t talk to me for a while and he wouldn’t return phone calls. He was a complicated guy.”

“Gina Andriolo: Dave approached boxing like a three-dimensional chess game. Regardless of the immediate issue he was dealing with, he was always looking three moves down the road. He had an amazing capacity for detail and kept meticulous records on everything. Every detail mattered. Most fight managers go to their fighters’ weigh-ins. Dave would find out when the scales were being calibrated and send me to make sure they were calibrated right.”

Harold Lederman: “Dave knew boxing; no question about it. He was a great boxing guy. But he was a tough guy to deal with when it came to officials. He was always arguing he didn’t want this referee or that judge to work his fighter’s fight. He never argued that he didn’t want me, but there were a lot of guys he didn’t want. And he argued long enough and hard enough that he was usually able to get rid of the guys he didn’t want. That’s one of the things that made him a great manager.”

Jon Wolf: “Before one of Ray Mancini’s fights in Las Vegas, Dave told everyone in the entourage, ‘No one is to gamble until the fight is over.’ He didn’t want anyone leaving whatever good luck we might have on the casino floor or bringing any kind of bad luck in. That same trip, Dave sent me downstairs to buy copies of all the newspapers they had so he could read what was being written about the fight. I had four nickels left over after I bought the papers. So I put a nickel in a slot machine, and five dollars worth of nickels came out. I played a few more nickels with similar results and went back upstairs with the newspapers and a bucket full of nickels. Dave took one look and asked, ‘What the f*** is that?’ I explained, and he told me, ‘Get rid of them.’ So I took the nickels downstairs, found an old lady who was playing the nickel slots, and said to her, “Excuse me, ma’am. I just won these and God told me to give them away.'”

Artie Pelullo: “Dave was a strange quirky guy, very opinionated. A lot of people thought he was a pain-in-the-ass to deal with, but I never had a problem with him. He came to me with Lonnie Bradley, and we did a couple of fights together. He wasn’t the kind of guy you went to a bar with for a couple of drinks and light conversation. But you could make a deal with him and his word was good. I liked him.”

Seth Abraham: “Dave didn’t care much about pleasantries and what I would call conventional business practices. Several times, he came to meetings at HBO wearing shorts. It wasn’t important but it was unconventional and it sticks in my mind. He was very perceptive and very bright. He always presented his case well. And as best I could tell, he was always honest with me. If you’re in boxing, you have to learn who the honest people are and who are the dishonest people. As a TV executive, I did business with both. And I can honestly say, I never had any integrity issues with Dave.”

Russell Peltz: “I didn’t know Dave well, but I don’t think he liked me very much. I say that because, one time, I wanted to make a match with one of his fighters and Dave told the fighter he didn’t trust me. What had happened was, a few years earlier, Dave was managing Duane Bobick and wanted a comeback fight for Bobick after he’d been knocked out by John Tate. I offered him George Chaplin as an opponent and told Dave that Chaplin couldn’t fight, which I believed was true. So Bobick and Chaplin fought in Atlantic City, Chaplin knocked him out, and Dave never trusted me again.”

Gina Andriolo: “He loved his fighters. He believed in his fighters. And he looked after his fighters in every way. His philosophy was, a fighter should get in and out of boxing as quickly as possible with as little damage as possible and as much money as possible. God, he fought for his fighters. I remember, one time, Dave got particularly angry when a promoter who shall remain nameless sent him a contract he didn’t like. It wasn’t what Dave thought they’d agreed to. I was doing Dave’s legal work at the time. He was shouting at me, ‘Call that m*********** up and tell him no f***ing way. He can take his contract and shove it.’ So I called the promoter up and – I was being tactful – I said, ‘Dave has a slight problem with paragraph 4(B). Is there any way we can change it?’ And Dave started screaming at me, ‘That’s not what I said. I said tell him he’s a m*********** and he can shove his contract up his ass.’”

Ray Mancini: “There were times when I said to myself, ‘This guy is out of his mind.’ Some of the things he asked for from promoters bordered on the ridiculous. Dave could take years off a promoter’s life. Lots of managers threaten to call a fight off. When Dave threatened to call a fight off, the promoter knew he might.”

Ray Leonard: “My best memories of Dave Wolf are from when I fought Donny Lalonde. He truly believed in Donny and the other fighters he worked with. We were cool with each other. What stands out most with me is that there was always respect between the two of us.”

Gina Andriolo: “There were always enormous piles of old newspapers and boxing magazines all over the apartment. Sometimes, that was a source of conflict between us. I’m not talking about a reasonable number of papers. I’d ask, ‘Why do we have to have ten-year-old newspapers stacked in the kitchen cabinets?’ But Dave needed them there to be happy. And he knew where every piece of paper was. God forbid I should move a piece of paper and he couldn’t find it.”

Jon Wolf: “Dave and I shared a bedroom when we were young. One time – I was three or four years old – my parents came home and Dave had built a wall in the bedroom out of chairs and whatever other furniture he could move so I’d stay on my side of the room and leave his toys alone and not knock his blocks over or mess up whatever game he was playing.”

Toby Falk: “There were piles of newspapers and magazines all over the apartment; thousands of magazines going back for years. In what I suspect was a major concession, he’d let Gina put flowery wallpaper in the kitchen when they were married. But he covered it over with fight posters as soon as she moved out.”

Craig Hamilton: “Dave’s main thing as a collector was fight programs, which a lot of people aren’t interested in because they don’t display that well. He had a solid fight program collection; Johnson-Jeffries and some other good ones. He wasn’t much of an autograph guy. He had a few good on-site posters, including one from Ali-Frazier III in Manila, and a lot of Ray Mancini stuff that had some value because Ray has a following, particularly in Ohio. But for someone who was obsessed with collecting, Dave’s collection wasn’t that good. Most of the rest was garbage. Dave had thousands of magazines that were virtually worthless. I’m not talking about old Ring magazines from the 1920s and 30s that are worth something. I’m talking about magazines from the 1970s and later that you can’t give away. Maybe a hospital will take them. They were stacked all over his apartment – in piles on the floor, on shelves, in closets, every place imaginable. There were piles and piles of magazines – three, four feet high – blocking access to bureau drawers and file cabinets. And they hadn’t been dusted in years. You could see that from the cobwebs. Obviously, they had meaning to Dave. They were very personal for him. But it wasn’t the place you’d bring a woman on a first date if you were trying to impress her. God bless Toby; I don’t know how she put up with it.”

Larry Merchant: “In a game that rewards individual initiative, Dave was a guy who jumped in, did his thing, and did it well. He was one of the more interesting characters in a business full of characters.”

Toby Falk: “Both of us had been married and divorced twice, so we didn’t feel the need to get married again. But we lived together for almost twenty years. He wasn’t well for much of our time together. There were complications from diabetes and some other problems. When he was fifty-five, he was diagnosed with leukemia. He didn’t fear death. He just didn’t want to be incapacitated or linger. He was cremated, so I can’t say he’s turning over in his grave over what’s happening now in America. But Dave was anti-authoritarian and very politically aware. And he hated injustice. Wherever he is now, I’m sure he’s very upset by Donald Trump.”

Ray Mancini: “Dave showed how the job should be done. He battled for everything for me. There were things other managers let happen to their fighters that Dave would never have let happen to me. What he did for my career, I can never thank him enough. I loved him. I loved him dearly.”

And a note in closing . . .

Dave and I became friends in his later years. I don’t use the term “friends” lightly. We had lunch together on a regular basis and talked often about people and events that had shaped us. As I wrote when he died, “Much of Dave’s anger stemmed from the fact that he hadn’t learned to read in a meaningful way until the age of twelve and thus had been labeled ‘dumb.’”

When Dave was young, dyslexia and other reading disabilities weren’t understood. The fact that he was able to surmount them to write Foul was remarkable in itself.

It was extraordinarily painful for a young boy with a high IQ who was sensitive in many ways to be labeled “dumb.” One way Dave dealt with the pain was to construct a hard exterior that served as a protective shell. Explaining that to me over lunch one day, Dave told me a story.

Once, when Dave was in grade school and the teacher briefly left the classroom, one of the boys started teasing him in front of the other children, saying that Dave couldn’t read.

“I can read,” Dave said.

“Prove it,” the boy countered. Then he went to the blackboard and wrote something in chalk. “Prove you can read. Read this.”

So very laboriously, Dave read aloud: “Dave . . . Wolf . . . is . . . stupid.”

More than a half-century later, Dave remembered that moment very clearly. And it still scarred him.

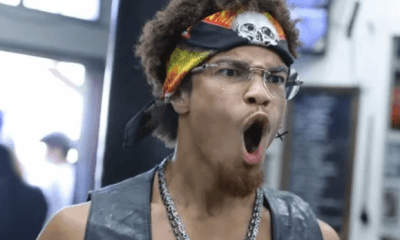

Photo: Dave Wolf with Donny Lalonde and Teddy Atlas. Photo undated but circa 1986.

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at thauser@rcn.com. His most recent book – There Will Always Be Boxing – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing

journalism.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Shafting of Blair “The Flair” Cobbs, a Familiar Thread in the Cruelest Sport

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden