Featured Articles

The Ali-Shavers Fight and the Ever-Present Open Scoring Debate

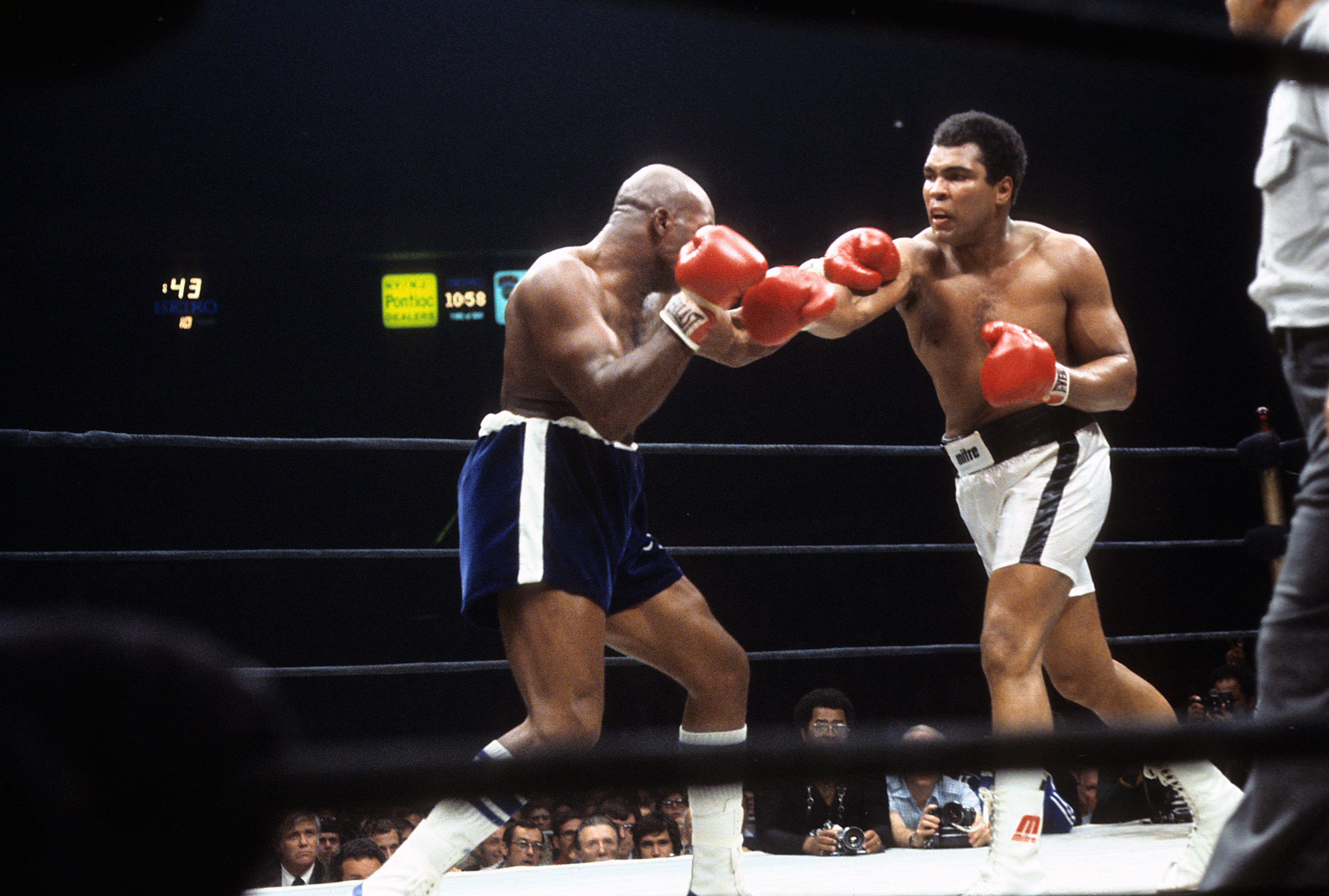

Saturday, Sept. 29, marks the 41st anniversary of Muhammad Ali’s last successful title defense. The 35-year-old Ali defended his WBA and WBC belts against Earnie Shavers, a devastating puncher, but otherwise limited, in Madison Square Garden. Those tuning in to the Thursday night fight on NBC, an estimated 70 million, were able to track the round-by-round scoring. And therein lies an interesting tale.

A bit of background. Technically, the first instance of open scoring, at least as it pertained to television, was to have been implemented by Ted Nathanson, producer for NBC Sports, which televised the May 11, 1977, heavyweight bout pitting Ken Norton against Duane Bobick in Madison Square Garden. Although on-site spectators would not have been privy to round-by-round scoring, the TV audience would have had such access. The grand experiment proved dead on arrival, however, when Norton needed only 58 seconds of the first round to blast out Bobick.

Nathanson was nothing if not determined, however, and he successfully lobbied for the same format to be used for the Ali-Shavers fight. As was the case for Norton-Bobick, spectators in the arena would not have the same access to the round-by-round scoring as would NBC viewers. The New York State Athletic Commission, then headed by former heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson, signed off on the arrangement with NBC with some hesitation.

John F.X. Condon, vice president of Garden Boxing, said he originally had planned to show the round-by-round scoring on the huge overhead screen to the 14,613 on-site spectators, but he decided against it. “We didn’t think it was wise,” Condon concluded. “Personally, I think it also detracts from the pleasure of watching at home. Fight fans like to get involved. They like the uncertainty of waiting for the final decision.”

Even more adamant in his opposition to open scoring, in any form, was legendary Garden matchmaker Teddy Brenner, who said he would do everything in his power to ensure that the NBC experiment would be a one-and-done, at least if he had anything to say about it. “I am against it,” Brenner stressed. “We at the Garden plan to do something about it.”

Unlike Norton-Bobick, Ali-Shavers would go the 15-round distance, with scoring on a round basis instead of the 10-point-must system now in place. Ali won by 9-5-1 on the card submitted by referee Johnny LoBianco and by 9-6 on the cards turned in by judges Tony Castellano and Eva Shain, the latter of who made history as the first woman ever to work a big-time fight. It was Ali’s 19th victorious title defense.

Garden officials were embarrassed, however, when a question of fairness was raised. The NBC telecast was shown in Ali’s dressing room, and a runner was assigned to keep Ali trainer Angelo Dundee informed of the judges’ evolving scores. The Shavers dressing room did not have similar access, which led his manager, Frank Luca, to complain of preferential treatment being granted to Ali. He said the NYSAC even attempted to obligate the fighters to use 10-ounce gloves instead of eight-ouncers, a change which was not approved but would have been detrimental to the harder-hitting challenger.

When informed of a playing field seemingly tilted to favor Ali, Patterson said the NYSAC never again would consent to open scoring at any venue in the state, be it for on-site spectators or just TV. “That will be stopped,” Patterson said. “I understand Angelo Dundee had someone running back to get him information and the other corner didn’t. That’s not fair. It could influence a fight, affect gambling in the arena with cheaters. It was not a success and it will never happen again.”

Shavers, who went into the Ali fight with a 54-5-1 record that included 52 wins inside the distance, said he might have fought differently – yeah, right – had he been apprised of the round-by-round scoring. “My corner told me I was ahead,” he lamented. “I didn’t go for the knockout. I would have put more pressure on him, taken more chances.”

Promoter Don King pushed for open scoring on May 5, 1994, at a Las Vegas press conference to hype the pay-per-view card two nights later at the MGM Grand headlined by WBC super lightweight champion Frankie Randall’s rematch with Julio Cesar Chavez, whom he had controversially outpointed nearly four months earlier.

“Progress can’t be stopped,” King said with his trademark bluster and hyperventilation. “It’s time for a change. Bring boxing out of the dark and into the light. People who go to football and basketball games know what the score is at all times. Why should boxing be the only sport where judges pass little scraps of paper back and forth and nobody else knows who’s winning until the end?”

King said he had been “excoriated and vilified” for having promoted two bouts during the previous eight months that ended in questionable decisions, and that open scoring could eliminate or reduce the problem.

“If anything controversial happens, people will be calling for (WBC president) Jose Sulaiman and me to be ridden out of town on a rail,” King continued. “One little controversy and these four great (rematches, the others being Simon Brown vs. Terry Norris, Gerald McClellan vs. Julian Jackson and Azumah Nelson vs. Jesse James Leija) suddenly become secondary. I don’t want that to happen.”

His Hairness indisputably was on target in noting that the two referenced bouts, in which Pernell Whitaker retained his WBC welterweight title on a majority draw against Chavez on Sept. 10, 1993, and Randall nipped Chavez on a split decision in large part because JCC had been docked two penalty points by referee Richard Steele, were controversial. Most ringside observers had Whitaker winning eight to 10 of the 12 rounds in San Antonio, Texas, and were it not for the two penalty points Chavez would have won a split decision instead of losing by the same margin.

Although King advocated for open scoring to be instituted immediately, he had to know that the wheels of change do not move that swiftly in Nevada or any other jurisdiction. But Marc Ratner, the executive director of the Nevada State Athletic Commission, while expressing his own doubts as to the usefulness of open scoring, said such a proposal at least merited further scrutiny.

“For this particular card, there will be no open scoring,” Ratner said. “But we’re not ostriches. We don’t have our heads in the sand. This is an issue that should be studied.”

Studied and almost certainly likely to be rejected, as it later was by the NSAC, for reasons that to Ratner were even more glaringly obvious than those offered by King for the other course of action.

“What if two fighters accidentally butt heads in the fourth round and one of them suffers a cut?” hypothesized Ratner. “If the bleeding fighter is ahead on the scorecards, his corner might be tempted not to close the cut, thereby prompting the bout’s premature conclusion and a decision victory.”

An even more compelling reason to forever squash the notion of full-blown open scoring holds that a fighter, if he knows he is sufficiently ahead entering the late rounds to be uncatchable on the scorecards, would get on his bicycle and pedal around the ring to eliminate or at least reduce the risk of being knocked out. Such a safety-first approach would drain whatever measure of hope still existed for the losing fighter banking on a puncher’s-chance turnaround.

We haven’t heard the last of the open scoring debate. The subject came up again in the aftermath of the Golovkin-Alvarez rematch, a tightly contested bout which Alvarez won by majority decision, much to the displeasure of Golovkin and his supporters. But for now, fight fans must continue to live with the occasional scorecard that defies credulity. And while too much controversy is never a good thing, some of it helps sell the sport and keeps interest high up to and even beyond the final bell. The alternative is the elimination of uncertainty, and with it the magic that sometimes is produced when two fighters believe success hinges on giving maximum effort to the very last punch.

Bernard Fernandez is the retired boxing writer for the Philadelphia Daily News. He is a five-term former president of the Boxing Writers Association of America, an inductee into the Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Atlantic City Boxing Halls of Fame and the recipient of the Nat Fleischer Award for Excellence in Boxing Journalism and the Barney Nagler Award for Long and Meritorious Service to Boxing.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers