Featured Articles

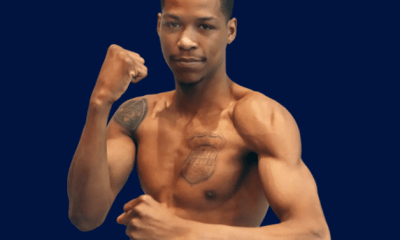

Deontay Wilder is a One-Man Rolling Tide in His Own Right

As a first-semester freshman at Shelton Community College in his hometown of Tuscaloosa, Ala., Deontay Wilder had the same dream that many boys and young men in that state have harbored almost since birth. Tall, lean and athletically gifted, he would earn an associate degree at Shelton CC, then walk on at the University of Alabama where he could imagine himself starring for his beloved Crimson Tide as a wide receiver on the football team or a forward on the basketball squad. Maybe, he dared to believe, he could play and excel in both sports en route to being awarded the college degree his mother fervently hoped would be her son’s ticket to a better life.

But destiny had other plans for Wilder. His infant daughter, Naieya, was diagnosed with spina bifida, a congenital condition that affects the spine and usually is apparent at birth. Raised to believe that a real man is responsible for taking care of his children, Wilder dropped out of Shelton and took jobs that paid actual money, if not a whole lot of it, rather than hope to be drafted by the NFL or NBA, a long shot dependent, of course, on his even making one of Alabama’s varsity rosters and doing well enough to draw pro scouts’ attention.

It has been a meandering road for Wilder from former community college student to IHOP waiter to Red Lobster kitchen worker to Olympic bronze medalist in boxing and, since his unanimous decision over Bermane Stiverne on Jan. 16, 2015, WBC heavyweight champion. The kid who once fantasized about catching touchdown passes and sinking jump shots in the cauldron of Southeastern Conference competition is now 33 years old, a multimillionaire and emerging state treasure famous enough to have been asked by Alabama football coach Nick Saban, who has led the powerhouse Tide to five national titles in the last 11 years and is bearing down on a sixth this season with a top-rated, undefeated team, to occasionally deliver motivational speeches to the red-clad players to whose ranks Wilder once hoped to join.

It wouldn’t be all that surprising if Saban again brought Wilder (40-0, 39 KOs) — who makes the eighth defense of his WBC title Saturday night against former champ Tyson Fury (27-0, 19 KOs) at the Staples Center in Los Angeles — to give another rah-rah pep talk to the Crimson Tide if they make it to the national championship game on Jan. 7 in Santa Clara, Calif. After all, Wilder has shone on a stage that stretches beyond the boundaries of his state or even his country. It has been said that the heavyweight champion of the world holds the most prestigious title any athlete can have, although the proliferation of sanctioning bodies and multiple claimants to that distinction have diluted its historical importance. But a victory over former lineal champ Fury, and especially if it comes in the form of another exclamation-point knockout, would do much to bolster Wilder’s contention that he truly is the best of the best, the “baddest man on the planet,” and worthy of being mentioned in the same breath with some of the greatest champions and hardest punchers ever to have graced the division.

“Alabama is the national champion,” noted Jay Deas, Wilder’s co-trainer and the man who introduced him to all the possibilities that a foray into boxing might offer someone with his signature skill. “Deontay is a world champion.”

And not just some itinerant holder of an alphabet title whose place in boxing history is written in pencil and not indelible ink. To Wilder’s way of thinking, it is the awesome power he brings to his work – primarily packed in an overhand right that can instantly turn an opponent into a twitching heap of humanity – that stamps him as a special fighter, worthy of taking his eventual place in the pantheon of such big-man blasters as Mike Tyson, Sonny Liston, Joe Louis, George Foreman, Rocky Marciano, Earnie Shavers, Jack Dempsey, Joe Frazier and Lennox Lewis. Put it this way: Wilder has no intention of letting the outcome of his high-visibility pairing with Fury rest in the hands of the judges.

“I say I’m the best. I say I hit the hardest. I say I’m the baddest man on the planet, and I believe every word that I say,” the confident-to-the-point-of-cockiness Wilder said of the great equalizer he possesses and will neutralize anything Fury might have going for him because, well, when hasn’t it? “I’m all about devastating knockouts. That’s what I do. (Fury) knows he’s going to get knocked out. So he can whoop and he can holler, he can build himself up. But he’d better meditate on this situation because he’s going to feel pain that he never felt before.”

High-volume knockout heavyweights come in all shapes and sizes, and the power source from which they draw is not always readily evident to the untrained eye. Some fighters have ripped physiques that look more appropriate for contestants in a Mr. Universe contest, but they don’t hit especially hard, the impressively muscled Shavers being a notable exception. Foreman and Liston had thicker bodies and huge fists capable of almost casually dispensing blunt-force trauma. Tyson, Frazier and Marciano were stumpy, short-armed guys who could knock a brick building down with a single shot. And Wilder? Well, he’s 6-foot-7, with a stretched-out weight distribution that suggests an Olympic swimming champion more than a fighter capable of knocking larger men silly. To some – like, for instance, Fury, who at 6-foot-9 and 260 or so pounds is anything but lean – the WBC champ looks almost gaunt.

“How am I going to let this little, skinny spaghetti hoot beat me?” Fury asked, rhetorically.

Wilder doesn’t necessarily dispute the notion that he is pretty much a lightweight for a heavyweight in an era where more and more of the sport’s big boys are beginning to resemble the Alabama defensive ends that he could never have been unless he wolfed down maybe six or seven carb-loaded meals a day. A bronze medalist at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, hence his nickname of the “Bronze Bomber,” the closest physical approximation to Wilder might be the welterweight version of Thomas “Hit Man” Hearns, who also had a spindly build but a sledgehammer of a right hand.

“I don’t care how big he is,” Wilder said of the taller (by two inches), much heftier Fury. “I done fought big fighters. Everybody I’ve fought has outweighed me. (Actually, it’s only 35 of 40.) But when you possess my kind of power, you don’t worry about a lot of things, man. I got the killer instinct. I got the most feared, the most dangerous killer instinct in the boxing game. It’s natural. It’s born.”

It is axiomatic that big hitters are born, not made, which might not be entirely accurate when you consider that the very young Tommy Hearns, who found his way into the late, great Emanuel Steward’s Kronk Gym in Detroit, didn’t have much pop until he learned some of the finer points of power punching, like hip rotation and turning your fist over at the moment of impact. But Wilder was basically a grown man of 20 when he checked out Deas’ gym in Tuscaloosa and learned, as Deas soon did, that the tall, skinny guy had a gift that might translate into something of value greater than a weekly $400 check from Red Lobster.

After taking a bronze in Beijing as a relative neophyte (he had an OK but hardly extraordinary 30-5 amateur record), the still-learning Wilder turned pro at 23 with a second-round knockout of Ethan Cox on Nov. 15, 2008, in Nashville, Tenn. Wilder weighed a career-low 207¼ pounds for his debut and, in what would become something of an oddity, actually outweighed Cox by 6½ pounds. Over the course of his 10-year pro career, Wilder – who has come in for three fights at a career-high of 229 pounds – has averaged 220.2 pounds per bout to 242.9 for the guys he’s been blasting out, although that gap might not be quite so wide were it not for the two chubbos who made the scales groan at 398 and 352½, respectively, that a still-rough-around-the-edges Wilder got out of there in the first round.

Only one opponent – then-WBC champ Stiverne, whom Wilder dethroned – has gone the distance with the “Bronze Bomber,” but Stiverne was decked three times in losing a one-round quickie on Nov. 4, 2017, meaning that the heavyweight champion with the highest career knockout percentage has kayoed every man he has been paired with as a pro. True, Wilder’s victims haven’t all been top-shelf, but that hasn’t been for a lack of trying. Fury’s scoffing putdown that 35 of Wilder’s 40 victories have come against “total tomato cans who can’t fight back” notwithstanding, Deas correctly points out that Wilder was poised to go to Moscow to fight the very formidable Russian Alexander Povetkin, a bout that went by the wayside when Povetkin tested positive for a banned substance, and he was insistent on proceeding with a twice-postponed matchup with the even more formidable Cuban southpaw Luis Ortiz after Ortiz twice tested positive for performance-enhancing drugs. Wilder, who was in trouble himself in the seventh round, won that slugfest on a 10th-round KO on March 3.

“Deontay and Tyson Fury both let their representatives know this was the fight they wanted, this was the fight the public wanted,” Deas said in holding the bout up as proof that his guy was willing to fight anyone, at any time and any place. “It’s a huge fight between undefeated fighters. Both guys should be commended for stepping up and giving the fans a fight they really want to see.

“But that’s Deontay Wilder. He will be involved in the two biggest heavyweight fights of 2018, having fought Ortiz and Fury. Nobody can match that resume. Joshua fighting (Joseph) Parker and Povetkin just doesn’t stack up. And if – when – Deontay beats Fury, I think he deserves to be recognized as Fighter of the Year.”

It is reasonable to believe Wilder will be one of two finalists for all the Fighter of the Year awards on the strength of wins over Ortiz and Fury, if he survives the upcoming test, arguably the biggest challenge of his career to date. His primary rival as the top fighter of 2018 would be undisputed cruiserweight ruler Oleksandr Usyk, who also has had a very commendable year with victories over quality opponents Mairis Breidis, Murat Gassiev and Tony Bellew.

But, as the recent mid-term U.S. elections should have demonstrated, the only sure thing in boxing, as in politics, is that there are no sure things. It’s wonderful to have confidence in yourself, but Wilder’s pronouncements of virtual invincibility call to mind Mike Tyson’s mistaken belief that he, too, was too good to ever lose to anyone inside a roped-off swatch of canvas. That idea went by the boards, of course, when Tyson was felled by 42-1 longshot Buster Douglas in Tokyo.

Reminded that Fury has always had a difficult style to decipher, Fury said with a vintage Mike Tyson-level of imperiousness, “I will figure him out. I don’t know when it’s coming, but when it does come, it’s good night, baby. I’m a true champion. A true champion knows how to adjust to anybody, any style. Fury has a lot of great attributes, but I’m the best in the world. And I’m going to prove it again. My confidence is over the roof.”

Whoever survives Saturday night’s fight likely moves on to a clear-the-decks showdown with WBA/WBO/IBF heavyweight champ Antony Joshua in 2019. But that won’t just be a fight to determine the best heavyweight of the here and now; to the winner likely goes the opportunity to sit at a table reserved only for the bluest-blooded members of heavyweight royalty. It’s a highly exclusive club, and Wilder is impatient to receive his invitation.

“I’ve worked my ass off to get to this very point in my life,” he said. “And now I’m here.”

Bernard Fernandez is the retired boxing writer for the Philadelphia Daily News. He is a five-term former president of the Boxing Writers Association of America, an inductee into the Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Atlantic City Boxing Halls of Fame and the recipient of the Nat Fleischer Award for Excellence in Boxing Journalism and the Barney Nagler Award for Long and Meritorious Service to Boxing.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this article at The Fight Forum, CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

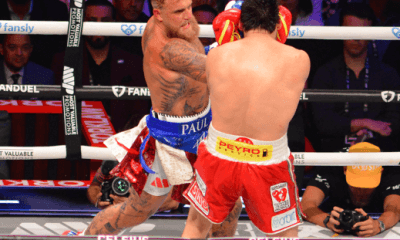

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

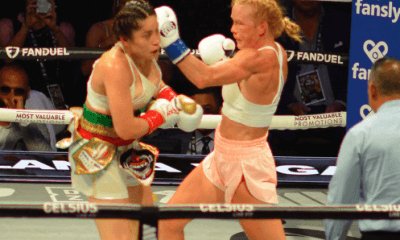

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates