Featured Articles

California’s Top Referee Jack Reiss Stood Tall in 2018

More than five weeks have elapsed since Deontay Wilder and Tyson Fury engaged in a memorable heavyweight title fight at the Staples Center in Los Angeles and fight fans are still buzzing about it. And henceforth, whenever the bout is re-visited, the name of referee Jack Reiss will figure prominently in the storyline.

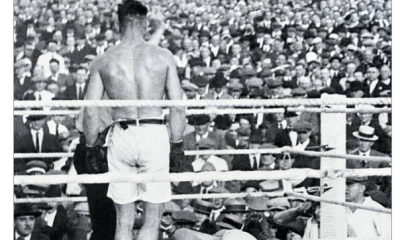

The crowning moment of the fight came 40 seconds into the final round when Wilder smashed Fury to the canvas with a right-left combination. Fury was on his way down when Wilder delivered the apparent coup-de-gras and when he hit the canvas it appeared that he was out cold. For five seconds he lay prone. He didn’t even twitch.

Many referees would have waived the fight off immediately. Not Reiss. Hovering over Fury on both knees so that he could peer directly into the eyes of the stricken fighter, Reiss began the “10 count.” By some miracle, Fury beat the count, ostensibly by one-tenth of a second. Reiss then checked and double-checked and triple-checked to see if Fury was fit to continue, instructing him to walk toward him and then away from him and then turn back toward him.

Not everyone agreed with Reiss’s decision, but the view from here is that Fury vindicated him. Before the round was over, the Gypsy King was back to his old showboating self. He even tagged Wilder with a few crisp punches in the final minute. The judges ruled the fight a draw but Fury was the winner in the court of public opinion.

Fury vindicated Reiss and Reiss vindicated Andy Foster, the head honcho of the California State Athletic Commission. More about that in a minute.

Jack Reiss was born in 1956 in the Coney Island neighborhood of Brooklyn. His father, a Romanian immigrant, died when Jack was eight years old, leaving his mother, who never remarried, to raise Jack and his two older siblings alone. In his teen years, Jack participated in all sports that didn’t require expensive equipment and developed an interest in martial arts.

In 1979, while rehabbing a broken foot caused in a kickboxing match, Reiss visited L.A. and never left. He joined the fire department, retiring after 31 years with the rank of captain. He and his wife Josephine have been married for 34 years and have two sons. In his civilian life, he is a real estate agent with an office in Oxnard. His twitter page has a feminine side; it’s hardly what one would expect from a man who has been around so much blood. It is chock full of household organizing and home maintenance tips.

Reiss, who is also a judge (as are all of California’s referees) estimates that he has worked more than 2000 fights since his first assignment in 1998. BoxRec credits him with far fewer, but shows him refereeing fights in 11 foreign countries including multiple visits to Germany, Singapore, Australia, Thailand, Panama, the Philippines, and Japan.

That Reiss has received so many plum assignments has left several of his colleagues disgruntled.

In April of this year, Wayne Hedgpeth and the two Raul Caiz’s, father and son, jointly filed a racial discrimination lawsuit against the California State Athletic Commission seeking damages of $100 million. Their ire was directed at the aforementioned Foster, a former amateur boxer and former amateur and professional MMA fighter who was picked to head the CSAC in 2012, assuming his post on Nov. 7 of that year after having previously served in the same capacity in Georgia.

In a letter filed by their attorney on April 27, 2018, the plaintiffs said “Of the 47 licensed officials in California, 33 are minorities (70.21 percent). Yet, the majority of championship fights for the period indicated above have been assigned to Caucasian officials…The system is not based on merit but on the sole discretion of an Executive Officer, Andy Foster.”

The plaintiffs noted that championship fights pay more and often lead to opportunities in other jurisdictions. So this alleged discriminatory practice impacted not only their earnings but their “earning capacity.” It was further alleged that there had been instances where a world sanctioning body picked a minority official only to be overruled by Foster who had the final say. Jack Reiss was identified as the primary beneficiary when these unspecified incidents occurred.

We’re not qualified to comment on the merits of the lawsuit. We have heard nothing more about it since muckraking journalist Zach Arnold harnessed California’s Public Records Act to obtain a copy of the attorney’s letter which he published on-line in July. It’s reasonable to assume, however, that Andy Foster felt some pressure to pick someone other than Jack Reiss to referee the Wilder-Fury match but ultimately went with his gut. Reiss had earned his trust.

This past summer, the Boxing Writers Association of America took the unprecedented step of reprimanding a referee. The object of their scorn was controversial Texas arbiter Laurence Cole who was assigned to work the Prograis-Velasco fight at New Orleans on July 14 and compelled the thoroughly beaten Velasco to take unnecessary punishment. Jack Reiss’s work in 2018 stood at the opposite end of the spectrum, a credit to his craft. If this web site were in the habit of naming a Referee of the Year, Reiss would have undoubtedly won in a landslide.

By the way, if there are any aspiring referees out there, Reiss has a bit of advice. “Above all,” he says, “it’s important to know what it feels like to take a punch.” Have fun with that.

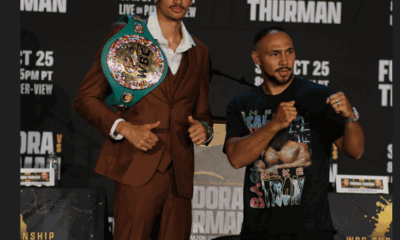

Photos credit: Esther Lin / SHOWTIME

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this article in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend