Featured Articles

This Day in Boxing History: Terrible Terry TKOs Little Chocolate

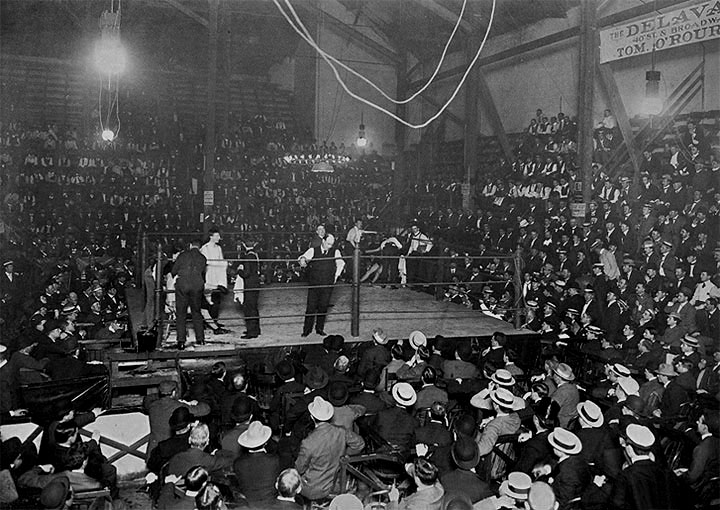

On Jan. 9, 1900, Terrible Terry McGovern and George “Little Chocolate” Dixon locked horns in the arena of the Broadway Athletic Club in New York City. Contested at 118 pounds, the bout between the exalted little gladiators – both of whom would enter the International Boxing Hall of Fame with the inaugural class of 1990 – was the first big fight of the 1900s and, in hindsight, the loudest example of a “changing of the guard” fight since Gentleman Jim Corbett upset John L. Sullivan in 1892.

Little Chocolate

George Dixon was born in 1870 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In those days, the maritime province of Nova Scotia had the largest population of blacks of any province in Canada, many of whom were descendants of former U.S. residents who were assisted in escaping to Canada by British sea captains after supporting the British in the American Revolutionary War.

In 1870, at age 17, Dixon turned up in Boston where he had his early fights. In his 12th bout, he was matched against a railroad brakeman. The match was scheduled for 12 rounds but went 14. The referee was unable to determine a winner after 12 and ordered two additional rounds. He was still unable to separate them after the extra sessions and the bout went into the books as a draw. There would be three rematches that produced the same result, the last of which went 26 rounds. (In this era, draws were endemic. Some veteran fighters finished their careers with more draws than wins and losses combined.)

It was in Boston that Dixon hooked up with Tom O’Rourke. A plasterer by trade, born and raised in Boston, O’Rourke exploited his political connections to become one of the most influential people in boxing, serving the sport as a matchmaker, manager, and promoter.

For a time O’Rourke controlled all four of the leading boxing clubs in New York. He managed the two leading black fighters of the 1890s, George Dixon and Joe Walcott, and promoted several fights involving the great black lightweight Joe Gans. But the pragmatic O’Rourke was an equal opportunity employer who would join the rush to find a Great White Hope when Jack Johnson won the heavyweight title.

O’Rourke brought Dixon to London in 1890 where he laid claim to the world featherweight title with a 19th round stoppage of Nunc Wallace. For the remainder of the century, Little Chocolate, as he came to be referenced, was recognized as the world featherweight champion, notwithstanding two losses, both on points, in bouts billed as world title fights. As a weight class, the featherweight division then had no fixed boundary. His bout with Wallace had a ceiling of 114 pounds. In subsequent title fights, he weighed as high as 125.

Dixon’s fame grew with each successful title defense and he came to be seen as invincible. Terry McGovern burst his bubble.

Terry McGovern

Ten years younger than George Dixon, Joseph Terrence McGovern was born in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, but his parents moved to Brooklyn before his first birthday and he grew up in that city, America’s fourth largest before it was folded into New York City in 1898.

The McGoverns lived in South Brooklyn in an area heavily populated by Irish immigrants, many of whom found work on the waterfront of the heavily polluted Gowanus Canal. It was a hardscrabble neighborhood but a close-knit neighborhood with a strong sense of community.

McGovern’s father died when Terry was 14. Three years later, after working as a newsboy and in a lumberyard, McGovern, carrying 110 pounds, made his pro debut in Brooklyn in a 10-round fight against an equally inexperienced opponent. Terry was disqualified in the fourth round (details are vague). The following year he was disqualified again, this coming in the 11th frame of a 25-round contest with Tim Callahan. These would be his only losses heading into his 1900 fight with George Dixon.

McGovern fought Callahan, a top shelf fighter from Philadelphia, three times in a span of four months. Their second meeting, which went 20 rounds, was ruled a draw. Terry knocked Callahan out in their third encounter. A left to the body followed by a right to the jaw put Callahan down for the count in the 10th round.

After one of these three fights — there are conflicting reports as to which one – McGovern’s contract was purchased by theatrical producer Sam H. Harris. The Broadway magnate sold a piece to his frequent collaborator George M. Cohan, the astoundingly prolific playwright, songwriter, and actor, and entrusted the day-to-day affairs of Terrible Terry to Joe Humphries, New York’s most prominent ring announcer. As was true of George Dixon, McGovern now had influential people in his corner.

McGovern’s first eight fights went the distance, but as he matured he became a knockout machine. Prior to meeting Dixon, he reeled off a string of 13 wins by KO, 11 coming within the first three rounds. The most eye-catching of these knockouts was a first round stoppage of England’s previously undefeated Pedlar Palmer. Their brief encounter played out in a makeshift arena in the little village of Tuckahoe, New York, 16 miles from midtown Manhattan.

The clever Palmer, who had one of boxing’s best nicknames – “Box o’ Tricks” – arrived in New York with great fanfare. Terrible Terry blew right through him. It was the first title fight under Queensberry rules that ended in the first round and it was a rousing performance by McGovern that had every bit the wow factor as Mike Tyson’s 91-second annihilation of clever Michael Spinks in 1988.

After this fight, reporters exhausted every synonym for typhoon to describe McGovern’s fighting style. He was a thunderstorm, a Krupp cannon, and a Gatling gun all rolled into one, said the prominent referee and pugilistic authority Charley White. But in the eyes of many, Terry, not quite 20 years old, was too wet behind the ears to defeat George Dixon. Lore had it that Little Chocolate had engaged in more than 800 bouts and had been knocked down only once. “More money was bet and won on Dixon than any half dozen fighters of his time,” noted a writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer.

The arena of the Broadway Athletic Club was relatively small, holding only four thousand. But 4800 squeezed their way in to see the fight, slated for 25 rounds, and at least half as many huddled outside in the cold, unable or unwilling to meet the steep price demanded by scalpers who did a brisk business.

The Fight

Dixon started strong. For four rounds, said a reporter, Dixon showed all of his marvelous old-time speed and proved superior when fighting at long range. During the battle, which lasted one second short of eight full rounds, Dixon staggered McGovern half a dozen times. But the Irishman stayed tight to his game plan which meant working the body to wear his adversary down.

In round seven, McGovern became a head-hunter. One of his punches appeared to break Dixon’s nose. It bled profusely. And then in the next round he battered Dixon all over the ring, knocking him down five times (some reports said eight) before Tom O’Rourke threw in the sponge. “It was,” reminisced New York Evening World sports editor Robert Edgren (who would be one of McGovern’s pallbearers), “the fastest and most sensational encounter at that weight that has ever been seen in this country.”

Postscript 1

Reporters wrote about the battle as if it were George Dixon’s final fight. To the contrary, he went on to have 76 more ring engagements, 48 in England, before retiring in 1906. During his career he answered the bell for an alarming 1744 rounds.

Thirteen months after his final fight, George “Little Chocolate” Dixon, once hailed as the greatest little man the sport of boxing had ever seen, died alone and destitute in New York’s Bellevue Hospital. The cause of death was said to be alcoholism. He was 37 years old.

Postscript 2

Twenty-three months after dethroning George Dixon, Terry McGovern lost his featherweight title to William Rothwell, a little known fighter from Denver who took the ring name Young Corbett II. Rothwell knocked him out in the second round in Hartford, Connecticut. It was a massive upset. Terry fought off and on for the next five-and-a-half years, but mostly in little 6-round fights where no decision was given.

McGovern went broke too. He squandered a good portion of his ring earnings backing slow horses at Coney Island racetracks. In 1907, Sam Harris arranged a series of benefits for him, the first of which was held on Jan. 23 at Madison Square Garden. McGovern was then a patient in a sanitarium in Stamford, Connecticut. He was in and out of sanitariums during the last 10 years of his life.

On Feb. 20, 1918, Terry wasn’t feeling well and checked himself in to Brooklyn’s Kings County Hospital. Two days later he was dead. The cause, depending on the source, was pneumonia complicated by nervous exhaustion or Bright’s disease complicated with acute indigestion.

In common with George Dixon, Terry McGovern was 37 years old when he drew his final breath.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds