Featured Articles

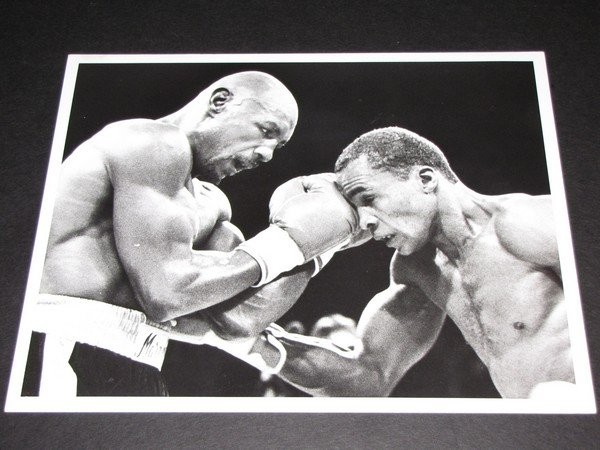

Sugar Ray Leonard and Marvin Hagler Stood Tall in an Era of Epic Battles

It’s been said — and it applies to all sports, but especially boxing — that in order to be great, one has to face great competition.

During the 1980s, in what many consider boxing’s “Golden Age,” several epic battles were waged between Roberto Duran, Thomas Hearns, Marvin Hagler and Ray Leonard, which helped drive the sport’s appeal after Muhammad Ali’s retirement in 1981.

All four are enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame, but Leonard and Hagler stood the tallest.

With each celebrating birthdays this month – Leonard turned 63 on Friday, May 17, and Hagler turns 65 on Thursday, May 23 – this seems like the perfect opportunity to reflect on their legendary careers.

Leonard, who would become a world champion in five weight classes, was a nonpareil ring craftsman who could box with absolute ease and also unload the heavy artillery.

Some said slick marketing after claiming the Gold Medal at the 1976 Montreal Olympics as a junior welterweight helped Leonard vault to fame. Sugar Ray had the look, personality and charm to attract a large fan base, but did he have what it takes to hold his own against the top welterweights?

The answer was yes, but it wasn’t until Leonard stopped Wilfred Benitez in the 15th round for the World Boxing Council and lineal welterweight title in November 1979 at Caesars Palace, that he would be given his due.

Entering the fight, Benitez had a 38-0-1 record and was a two-division world champion.

In the opening frame, Leonard drilled Benitez with a left hook after tossing a jab and a right cross.

Two rounds later, Leonard knocked Benitez on his backside with a rattling jab. “I wasn’t aware I was in a championship fight early because I hit him so easy,” said Leonard, who was named Fighter of the Year by The Ring magazine in 1979 and 1981, but then he adjusted to my style. It was like looking in a mirror.”

Leonard knocked Benitez down with a thunderous left in the 15th, but couldn’t put him away until the referee called it off with six seconds left.

“No one, I mean no one, can make me miss punches like that,” said Leonard of Benitez, who is also in the IBHOF.

In June 1980, Leonard, who went 36-3-1 with 25 knockouts, returned to the Canadian city where he first gained fame and faced the indestructible Duran, the former lightweight king, who came into the bout with a 71-1 record and was regarded as the best pound-for-pound boxer in the world.

The fight drew international attention and although Leonard lost, his showing removed any and all doubts about his greatness.

With 46,317 inside Olympic Stadium, Duran dictated the early pace by cutting off the ring and not allowing Leonard to extend his arms.

For four rounds, Duran didn’t give Leonard enough room to move and unload any significant blows.

Leonard finally came alive in the fifth and unleashed numerous combinations. The remainder of the fight saw Leonard score, but it was Duran who looked stronger and sharper.

William Nack, writing in Sports Illustrated described it thusly: “It was, from almost the opening salvo, a fight that belonged to Duran. The Panamanian seized the evening and gave it what shape and momentum it had. He took control, attacking and driving Leonard against the ropes, bulling him back, hitting him with lefts and rights to the body as he maneuvered the champion against the ropes from corner to corner. Always moving forward, he mauled and wrestled Leonard, scoring inside with hooks and rights.”

After 15 rounds, Duran won a very narrow but unanimous decision, handing Leonard his first setback after opening his pro career with 27 wins.

Angelo Dundee, Leonard’s trainer, had advised him to stick and move against Duran who wanted to brawl. But Duran was able to get inside Leonard’s head and Leonard, wanting to prove his toughness, did not follow Dundee’s advice.

Leonard realized his error and vowed not to make the same mistake if he met Duran again. And they did meet again, five months later, before a national television audience with 25,038 looking on at the New Orleans Superdome.

This time Leonard would fight his fight and not Duran’s. “The whole fight, I was moving, I was moving,” he said, “and voom! I snapped his head back with a jab. Voom! I snapped it back again. He tried to get me against the ropes, I’d pivot, spin off and pow! Come under with a punch.”

Late in a memorable seventh round, Leonard wound up his right hand as if to throw a bolo punch but instead tagged Duran’s face with a sharp jab.

Leonard then taunted him, sticking out his chin and daring Duran to hit it. The taunting continued as Leonard moved around the ring.

It was clear Leonard was ahead on all three scorecards, but it was still close, and Duran, though not hurt, seemed to lack real punching power and probably felt humiliated.

Toward the end of the eighth round, Duran turned his back to Leonard and uttered the now famous line “no mas” (no more).

It was over with 16 seconds left as Leonard regained the WBC and lineal welterweight belts.

Duran said he quit because of stomach cramps after overeating following the weigh-in. To which Leonard replied, “I made him quit…to make Roberto Duran quit was better than knocking him out.”

Leonard then agreed to meet Hearns in order to unify the welterweight title. They met on September 16, 1981, a sweltering night in Las Vegas, at an outdoor arena at Caesars Palace before 23,618. Hearns walked into the ring with a 32-0 mark and 30 knockouts, while Leonard had a 31-1 record with 22 knockouts.

In the early stages, Leonard stayed away and boxed while Hearns tried to find a hole in Leonard’s defense.

After five rounds, Leonard was trailing on the cards and had a swelling under his left eye. In the sixth, Leonard found his range and landed a left hook to the face and he was again the aggressor in the seventh.

Hearns decided to box and piled up points while Leonard wanted to unload the heavy guns.

Hearns dominated rounds nine through 12. But just before round 13, Dundee said to Leonard, “you’re blowing it, son! You’re blowing it!”

For the 13th, Leonard, who now had a badly swollen left eye, caught Hearns with a stunning right and then landed a clean combination as Hearns was on wobbly legs.

Hearns went through the ropes, but it wasn’t ruled a knockdown by referee Davey Pearl because it wasn’t a punch that sent him there.

Late in the same round, Hearns was decked after Leonard connected with multiple blows.

In round 14, with Hearns leading on all three cards but clearly out of gas, Leonard seized control with a sizzling overhand right and a combination that saw Pearl call a stop to the action.

A third round TKO over Bruce Finch in February 1982 with the WBA, WBC, and lineal welterweight titles on the table, was followed by a scheduled fight with Roger Stafford.

While in training, Leonard had problems with his vision. He was diagnosed with a detached retina which was repaired in May of that year.

In November 1982, at a charity event in Maryland, Leonard announced he was retiring from boxing.

Twenty-seven months passed before Leonard returned to the ring in May 1984, when he faced Kevin Howard in a non-title match.

In the fourth round, Leonard was knocked down for the first time in his career. He went on to win, TKOing Howard in the ninth, but then shocked everyone at the post-fight press conference by announcing he was calling it a career once again.

Leonard sat ringside for the Hagler-John Mugabi fight in Las Vegas in March 1986 and was surprised to see Mugabi actually outbox Hagler for much of the contest before succumbing in the 11th round.

Leonard had seen enough and announced two months later he was coming back and that his next opponent would be none other than the great Hagler who would be making the 13th defense of his middleweight title.

The fight was set for April 6, 1987 at Caesars Palace. Hagler opened a 4-to-1 favorite.

Leonard won the first two rounds on all three judges’ scorecards as Hagler, a natural left-hander, fought in an orthodox stance.

In the third round, Hagler switched to southpaw and fared much better, but Leonard remained in control with the help of superior hand and foot speed.

Leonard started to tire by the fifth as Hagler buckled his knees with an uppercut toward the close of the frame.

Hagler scored well in the sixth round, but Leonard also had effective moments.

Hagler did well in the seventh and eighth as he landed his jab while Leonard wasn’t able to counter.

The ninth round was the most exciting with Hagler stunning Leonard with a left cross and had him pinned in the corner.

Leonard was able to escape and though each looked sharp, Hagler’s punches were crisper and more resounding.

The 10th round wasn’t as dramatic, but Hagler took that stanza, while Leonard boxed sharply in the 11th.

In the fight’s final round, the 12th, Hagler landed a tremendous left hand that backed Leonard into the corner.

Leonard threw a flurry of punches and the round concluded with each fighter exchanging blows along the ropes.

The final CompuBox stats had Leonard landing 306 of 629 punches for 48.6 percent and Hagler connecting on 291 of 792 for 36.7 percent.

The fight was very close. Lou Filippo had it 115-113 for Hagler but was out-voted by Dave Moretti and Jose Guerra who had it for Leonard by scores of 115-113 and 118-110 respectively.

Hagler, who closed his career with a 62-3-2 mark and 52 knockouts, insisted he won the fight.

This was Hagler’s final time inside the ring and he would eventually move to Italy.

Prior to his famous battle with Sugar Ray, Hagler scored two of the biggest wins of his career, scoring a unanimous decision over Roberto Duran in November 1983 and stopping Thomas Hearns in the third round in April 1985. Both bouts were at Caesars Palace.

Here is Pat Putnam’s lead graph of the classic Hagler-Hearns fight as it appeared in Sports Illustrated: “There was a strong wind blowing through Las Vegas Monday night, but it could not sweep away the smell of raw violence as Marvelous Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns hammered at each other with a fury that spent itself only after Hearns had been saved by the protecting arms of referee Richard Steele. The fight in a ring set upon the tennis courts at Caesars Palace lasted only one second longer than eight minutes, but for those who saw it, the memory of its nonstop savagery will remain forever.”

After upsetting Hagler, Leonard waited 19 months before getting back in the ring. In November 1988, he defeated WBC light heavyweight title-holder Donny Lalonde via a ninth round TKO. The WBC also sanctioned this fight for their inaugural super middleweight title.

Leonard then faced Hearns in a rematch in June 1989 at Caesars Palace and though it was ruled a draw, many at ringside thought that Hearns, who knocked Leonard down twice, deserved the decision.

Six months later, at the Mirage in Las Vegas, Leonard met Roberto Duran in a rubber match. Leonard prevailed over Duran by unanimous decision.

There would be two more fights for Leonard before he retired from boxing for good. In February 1991 at Madison Square Garden he lost a unanimous decision to Terry Norris in a clash for the WBC junior middleweight crown.

Another retirement followed, but his career wouldn’t officially be over until March 1997 at Convention Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey, when Leonard, now 40 years old, was stopped in the fifth round by Hector Camacho with a fringe middleweight title at stake.

These last two fights were aberrations compared to Leonard’s glory days when he was the undisputed ruler of the welterweight division.

Few who watched Sugar Ray Leonard and Marvelous Marvin Hagler at their peaks will ever forget what they brought into the ring. No, they didn’t do it alone, but it’s unlikely anyone better than these two titans will appear any time soon.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

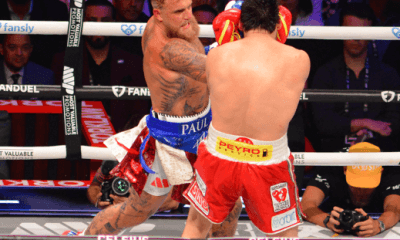

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates