Featured Articles

The Battle of Wits Between Roach and Birmingham May Decide PacMan vs. Thurman

The Battle of Wits Between Roach and Birmingham May Decide PacMan vs. Thurman

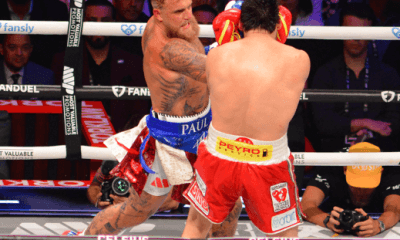

It is the boxers who are the center of attention, of course, and that is how it always has been and always should be. But there are a select few high-visibility bouts in which the lead trainers play a more significant role than usual, so much so that their prefight and in-fight strategizing could make the difference between victory and defeat for their guy.

Although it isn’t an undercard attraction in its own right, a mental scrap worth monitoring pits Freddie Roach, Manny Pacquiao’s longtime strategist and a seven-time winner of the Boxing Writers Association of America Eddie Futch Award as Trainer of the Year, against Dan Birmingham, a two-time BWAA Futch winner whose status as one of the elite trainers has dimmed somewhat over the past decade and a half. But the St. Petersburg, Fla.-based Birmingham’s reputation could be buffed and polished to its former sheen should Keith “One Time” Thurman win as spectacularly as he has vowed to do on July 20.

The matchup of Pacquiao vs. Thurman might turn out to be just such a fight in which a spotlight, for better or worse, is shone upon the handiwork of the trainers. Those in attendance in Las Vegas’ MGM Grand Garden Arena won’t able to hear their spoken instructions between rounds, but subscribers to the PBC on Fox Sports Pay Per View telecast should pay close attention to what takes place in those vital one-minute interludes when all the preparation that went before is either working as planned, or is undergoing a hurried rewrite on the fly. Seemingly unlikely victories have been procured, more often than casual observers of the sweet science might realize, because the chief second offers just the right bit of tactical advice or just the right inspirational message at precisely the right moment.

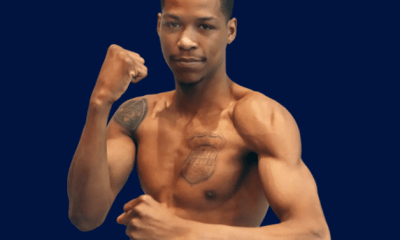

The prevailing story lines before the first punch that counts is thrown have been fairly standard stuff: Pacquiao (61-7-2, 39 KOs), the living legend and only world champion in eight separate weight classes, attempting to extend the outer limits of his prime at the improbable age of 40, and Thurman (29-0, 22 KOs), the WBA welterweight champion and 10 years Pacquiao’s junior, out to demonstrate that injuries and two-plus years of near-total inactivity haven’t done to him what the natural laws of diminishing returns might or might not have done to the Fab Filipino.

If there were sports books odds dealing with the corner battle involving Roach and Birmingham, Roach, a disciple of the late, great Eddie Futch who has had Pacquiao’s ear for their 16 years together, with the exception of a one-bout absence, almost certainly would be as much a favorite as Mike Tyson was over Buster Douglas or Anthony Joshua over Andy Ruiz Jr. Roach, 59, doesn’t need to make a case for his future induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame as he already has been enshrined, in 2012. Should Pacquiao demonstrate that he is still an elite fighter of the here and now instead of a cherished but faded icon of the past, Roach could take a step toward an almost-unimaginable eighth Futch Award.

And Birmingham?

Like Roach, a former lightweight who posted a 40-13 record with 15 knockouts in a professional career that spanned from 1978 to ’86, Birmingham is a life-long devotee to a sport that got under his skin at an early age and took permanent root. Unlike Roach, who at one point was 25-2 and world-rated under the tutelage of the sainted Futch, Birmingham, 68, never even sipped the proverbial cup of coffee as a pro. He began boxing at 15, weighing all of 112 pounds, in his gritty hometown of Youngstown, Ohio, until he decided that sun and surf were preferable to soot and rust, necessitating a relocation to more pleasant environs along Florida’s Gulf Coast.

There are other differences between Roach and Birmingham, both subtle and stark. As a devotee to Futch, Roach was always in relatively close proximity to the old master’s retinue of stars and hot prospects, laying the groundwork for Roach to begin his own career as a trainer, if not exactly at the top, then at least a ways removed from the bottom. Birmingham, whose other passion besides boxing is rock ’n’ roll – he describes himself as a “guitar-playing 1960s hippie who was at Woodstock” – also had a mentor in Ben Getty, Thurman’s original coach, who took the Ohio transplant on as an assistant trainer to Thurman, then a youthful prodigy.

And while Roach has long since established his bona fides apart from Futch, who was 90 when he passed away on Oct. 10, 2001, to some it might appear that Birmingham is still playing the role of understudy to Getty, who was 63 when he died unexpectedly in 2009.

Thurman was a seven-year-old kid with no discernible purpose in life when he came into contact with Getty, a former serviceman whose post-military life had been unceremoniously reduced to that of a janitor at a Clearwater elementary school. It was Getty who brought Thurman to his after-school YMCA boxing program, where he learned – and loved – to shadowbox, jump rope and spar. It was like the boxing version of Luke Skywalker mastering nuances of The Force under Obi-Wan Kenobi or Yoda.

“Ben Getty was a very special man,” Thurman said in 2015. “He was the one who taught me to go for the KO. He used to say this line that pissed me off a lot. I don’t know if he said it to piss me off, or if he just said it because he never wanted me to forget. But he used to say, `You are nothing without your power.’ It took me a long time to understand what that really meant.

“To me at first it was real basic. I took it as telling me I can’t box. Maybe to a degree he did mean that, but throughout the years as I reflect, I think he just never wanted me to forget how important my power is, and how my power has the ability to change the outcome of a fight.”

Getty’s sudden death left a still-developing Thurman at a career crossroads. Shelly Finkel, manager of or adviser to some of boxing’s greatest champions and biggest draws, recommended that Thurman turn himself over to Roach, whose Wild Card Boxing Club in Los Angeles had become a preferred destination for fighters such as himself, brimming with potential yet to be maximized. Thurman politely declined, choosing instead to remain on home turf and with Getty’s right-hand man, Birmingham, who might have been better known at that time than Getty thanks to those two Futch Awards. Thurman continues to publicly revere Getty, wearing trunks with “Ben” stitched across the waistband. You might think that Birmingham takes at least some umbrage to that, but he insists it isn’t so.

“It hasn’t been uncomfortable at all,” Birmingham said of his station as a sort of ersatz Getty, as far as Thurman is concerned. “Ben Getty and I were very close friends. I gave him the keys to my gym so he and Keith could come and go as they pleased. When Ben passed away, just a couple of days later Keith came to me and asked, `Would you take over?’ I said, `Absolutely.’

“Keith’s history with Ben makes my job a lot easier. I don’t have to teach him any basics, that’s for sure. We just analyze the opponent, see what we need to do on fight night to win, and I train him that way. Pacquiao is a diverse fighter. He’s got quick hands, quick feet and he’s a good boxer. He’s fairly unpredictable.”

Not so Thurman, who apparently is holding firm to Getty’s sacred mandate that punching power must remain his No. 1 priority. He has predicted that Pacquiao will go down inside of six rounds, which might be easier said than done even against a Manny who no longer is at peak form.

Make no mistake, though, Birmingham should not be considered a Getty clone that has slavishly adhered to every verse from the Gospel of Ben. In 2004 and 2005, the years he won his Futch Awards, Birmingham was boxing’s tastiest flavor of the moment. His charge Ronald “Winky” Wright, who was inducted into the IBHOF in 2018, outpointed Shane Mosley in a super welterweight unification showdown on March 13, 2004, and followed that up with another points nod over Mosley the same year. In 2005, Wright turned in a career-best performance, utterly dominating Felix Trinidad en route to a one-sided decision, to which he added another UD12 over veteran Sam Soliman.

While Birmingham primarily was recognized for his work with Wright, he augmented his rising profile by taking a lesser talent, 2000 U.S. Olympian, Jeff “Left Hook” Lacy, to the IBF super middleweight title in 2004. Lacy won four times in those two years, three coming inside the distance.

It should be noted that Wright, a clever southpaw who was never known for his ability to get opponents out of there with one shot or even a semi-fusillade of them, was far different stylistically than is Thurman. It therefore seems reasonable to assume that this updated version of Dan Birmingham is no more an exact duplicate of Ben Getty than Freddie Roach is of Eddie Futch.

There are different methods by which a trainer gets his fighter to rise to the occasion when the stage is most brightly lit. Angelo Dundee, Lou Duva and Richie Giachetti, all regrettably gone, embodied the motivational techniques favored by excitable men of Italian heritage. Who can forget Dundee, in maybe the signature moment of his remarkable career, forcefully telling Sugar Ray Leonard, “You’re blowing it, son!” after the 12th round of his epic welterweight unification matchup with Thomas Hearns on Sept. 16, 1981. An energized Leonard, his eyes swollen and behind on the scorecards, responded by flooring the Hit Man in the 13th round and stopping him in the 14th.

Futch and George Benton, also regrettably gone, were more professorial in their demeanor, rarely raising their voices and disinclined to resort to rah-rah stuff. If Thurman, who has a Nepalese wife and has walked the Himalayas in a quest to find some measure of inner serenity, were to seek out some ancient and wise soothsayer he could do worse than to come across some Tibetan version of a Futch or Benton.

So pay keen attention to the 60-second breaks between rounds when Roach – who, it should be noted, is listed as Pacquiao’s co-trainer, in addition to Manny’s friend and associate Buboy Fernandez – and Birmingham dispense their abbreviated instructions. Whoever wins those small battles of the brain might determine who wins the larger conflict inside the ropes.

Photo credit: Andy Samuelson / Premier Boxing Champions

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates