Featured Articles

The Hauser Report: A Sad Night for Fans of Chris Arreola

The August 3 fight at Barclays Center between Chris Arreola and Adam Kownacki highlighted what’s enthralling about boxing and also a sad side of the sport.

When Arreola turned pro in 2003, he seemed destined for success. He was a heavyweight with a good amateur pedigree, power, solid ring skills, and a crowd-pleasing, hit-me-and-I’ll-hit-you-back style. He was media-friendly and likable with refreshing candor and a good sense of humor. His Mexican-American heritage was a plus. And he was guided by Al Haymon at a time when HBO Championship Boxing and Boxing After Dark were all but programmed by Haymon, with Arreola, Victor Ortiz, Andre Berto, and Robert Guerrero being anointed “stars of the future.”

There were times when Arreola trained less diligently than he should have. A fighter doesn’t get more out of boxing than he puts into it, and Chris was rarely in top shape. Indeed, Henry Ramirez (who trained Arreola for most of his ring career) acknowledged, “Sometimes I don’t think he gives us the best chance to win. Sometimes he comes in a little too far out of shape.” But that was part of the package.

“Who gives a f*** if I’m fat?” Arreola asked rhetorically. “There’s plenty of guys who look like Tarzan and fight like Jane.”

Other “Arreolaisms” included:

* “Boxing is two guys in the ring who hardly know each other, beating the crap out of each other. The crowd oohs and aahs, and I want to get my oohs and aahs in. Then it’s over and you shake hands and hug each other. Go figure.”

* “My defense has to get better. I’m ugly and I don’t want to get any more uglier.”

* “I’m not big-headed. I’m one of the guys, a regular Joe Schmo. But it makes me angry when people think I’m dumb, when they talk down to me, when they think I’m a meathead because I’m a fighter.”

Ten years ago, Arreola’s record stood at 27-0 with only one opponent going the distance against him. Then, on September 26, 2009, he challenged Vitali Klitschko for the WBC heavyweight crown. Chris fought with honor but was outclassed from the opening bell. The outcome of the fight was never in doubt. Klitschko out-landed him 301 to 86 and turned him into a human bobblehead doll. Ramirez called a halt to the beating after ten one-sided rounds.

Arreola has been on a long downhill slide since then. Seven months after losing to Klitschko, he was outpointed by Tomasz Adamek. “He beat my ass,” Chris said in a post-fight interview. “I look like f****** Shrek right now.”

After being complimented on his “toughness” after losing a twelve-round decision to Bermane Stiverne in 2013, Arreola responded, “It doesn’t matter how tough you are. I lost the fight.”

Subsequent title opportunities against Stiverne (2014) and Deontay Wilder (2016) ended in knockout defeats.

Asked prior to fighting Wilder if he thought that, given his recent ring performances, he deserved another title opportunity, Arreola replied, “Let’s be honest, man. Do I deserve it? Come on. No. But when a title shot comes knocking, you don’t turn it down.”

The gaping hole in Arreola’s ring resume is that he has never beat a world-class opponent. His biggest win was a first-round stoppage of former Michigan State linebacker Seth Mitchell (who was 26-1-1 at the time). “He better bring his helmet if he expects to beat me,” Chris said before that fight. He also stopped a faded 39-year-old Jameel McCline short of the distance.

Readying to fight Kownacki, Arreola was 38 years old with a 38-5 (33 KOs, 3 KOs by) ring record that arguably wasn’t as good as it looked.

At the June 18 kick-off press conference for Kownacki-Arreola, Chris had a pensive look in his eyes. He was born with a fighter’s face that has been forged further in the fire of combat, adding scar tissue and a nose that has been ground every which way while being broken multiple times.

Once upon a time, Arreola was the A-side in main events. Not anymore. The 30-year-old Kownacki had built a 19-0 (15 KOs) record against the same class of fighter that Chris used to beat. Adam is a big strong guy who throws punches with abandon, wears opponents down, has minimal defense, and is being groomed as an opponent for Deontay Wilder.

Arreola was seated on the B-side of the dais. His name was listed after Kownacki’s on all promotional material. On fight night, he would be in the red (designated loser) corner. If the powers that be at Premier Boxing Champions thought he had a realistic chance of beating Adam, they wouldn’t have made the fight.

“How did Arreola feel about being the B-side of the promotion?”

“I’m okay with it,” Chris said. “It’s part of the game. Once I was a young lion and now I’m the old veteran. Boxing humbles you. But I’m not a stepping stone for anyone.”

How did he feel about Andy Ruiz upsetting Anthony Joshua to become boxing’s first Mexican-American heavyweight champion?

“I’m happy for Andy. The difference between Andy and me is, he made the best of his opportunities and I didn’t. Good for him. The first time we sparred together, Andy was seventeen years old. Back then, he wanted to be like me. Now I want to be like him.”

Kownacki’s fortunes have also changed but he’s going in a different direction. In 2015, Adam had made his Barclays Center debut in a swing bout on the undercard of Amir Khan versus Chris Algieri. Now he anticipated beating Arreola which, in his words, “would make me a top ten heavyweight on everyone’s list.”

“On paper, it’s the perfect fight,” Adam added. “Now it’s in my hands to do what I gotta do, which is get a knockout and put on a great performance.”

There were more sound bites from Arreola as the build-up to the fight progressed:

* (when asked to define himself): “I’m brash but respectful of other people. I’m a kind-hearted, old-school in a lot of ways. I’m at peace with myself. I’m me.”

* (about being a role model): “People ask me, ‘What do you say to kids?’ And I tell them, ‘I don’t say shit to kids. I talk to their parents and tell them to be there for their children.”

* (about his family): “My wife and I have two children, a 17-year-old daughter and four-year-old son. That’s thirteen years apart. But same father, same mother. Make sure you write that.”

* (about fighting Kownacki): “It’s not personal. I like Adam and I think he likes me. But I’m going to try to punch him in the face and knock him out, and that’s what he’s going to try to do to me.”

“How big a puncher is Adam?” Chris was asked.

“I’ll find out on Saturday night,” Arreola answered. “He’s fought some good fighters, but I’ve fought better.”

But the better fighters that Arreola had fought beat him.

The most pressing question in advance of the fight was, “How much did Chris have left?”

At a certain age, a fighter knows what to do in the ring better than he did before but he can’t do it anymore. And at 38, a fighter doesn’t take punches as well as he did when he was young. Arreola used to hate the rigors of training but liked sparring. Now he acknowledged, “I don’t mind training but I hate sparring. My body isn’t the same anymore. When I get hit now, it hurts more and the pain lasts longer.”

Arreola’s weight – an issue in the past – was down. He would enter the ring at 244 pounds, a better number than Kownacki’s career high 266. But was Chris in fighting shape? And with what he had left, would it matter?

Kownacki was a heavy betting favorite and noted that Arreola was “a little bit past his prime.”

“This is my last chance,” Chris responded. “If I lose this fight, I’ll retire, plain and simple. Not because of the media or anything like that. This is my last chance because I say so. If I lose, there’s no reason for me to be in the sport of boxing. I’m in boxing to be a champion. If I lose, it brings me all the way back to the bottom, and I don’t want to keep crawling back up and crawling back up again. I’m too old to be doing that. So it’s a make or break kind of fight. If I lose, I go home, no matter if it’s a great fight or it could have gone either way. Plain and simple; I lose it, I go home, I stay home. One and done, no more.”

Old athletes are surpassed by young ones in every sport. But it’s more painful to watch when the sport is boxing and the older competitor is getting beaten up.

There was a time when Arreola fought mostly in Southern California before crowds that were solidly behind him. Now he was in Brooklyn in a promotion aimed at Polish-American fans. Kownacki, who had fought at Barclays Center on eight previous occasions, was the house fighter. The announced crowd of 8,790 booed when Chris entered the ring and cheered wildly for Adam.

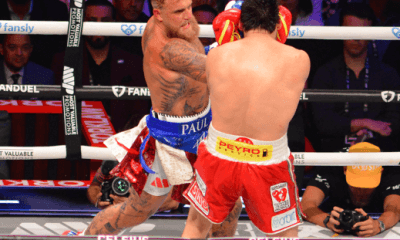

It was an exciting fight with little subtlety about it. One of boxing’s cardinal rules is, “Never give an opponent a free shot.” That said; both men fought like they didn’t understand that holding up their hands, slipping punches, and otherwise defending themselves is an integral part of the sweet science. They punched and mauled for twelve rounds in a non-stop slugfest that resembled two mastodons locked in battle for supremacy of the herd.

In the early rounds, it appeared as though Kownacki might walk through Arreola. He was a bit quicker, had a bit more on his punches, and seemed better able to absorb punishment. Then, in the middle rounds, Adam slowed a bit and one had to consider the fact that Chris had gone twelve rounds on four occasions and ten rounds thrice while Kownacki had gone ten rounds once. In other words, Arreola had been down this road before and might be better able to navigate the terrain as it got increasingly more rugged.

Then, in round nine, Arreola tired noticeably. From that point on, it seemed as though he was fighting from memory. But he never stopped trying to win. On the few occasions when Kownacki tried to slow the pace, Chris forced the action. One can question Arreola’s ring skills. One can question his judgment. His courage and heart aren’t in doubt.

The judges were on the mark with scorecards that favored Kownacki by a 118-110, 117-111, 117-111 margin. His limitations as a boxer showed in the fight and he lacks the one-punch knockout power that might compensate for them at the elite level. But Kownacki-Arreola was a barn-burner. According to CompuBox, Adam landed 369 of 1,047 punches while Chris connected on 298 of 1,125. That set CompuBox records for total punches landed and thrown in a heavyweight fight.

“Adam is relentless,” Arreola said in a post-fight interview. “He just keeps coming. I know I got him with some good punches and he got me with some good ones. I was more than ready to go all twelve, but Adam came in and won the fight.”

Then Chris went to the hospital to check on the status of his left hand and possibly more. Just before entering the ambulance, he acknowledged, “I’m a little dejected. I lost. This ain’t the way I wanted to go out, but I gave my all. Much respect to Adam. We were in a proverbial phone booth beating the shit out of each other, and it was fun. It was fun for me and it was fun for him and I hope the fans enjoyed the fight.”

Photo credit” Nabeel Ahmad / Premier Boxing Champions

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His next book – A Dangerous Journey: Another Year Inside Boxing – will be published later this summer by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival