Featured Articles

Javan ‘Sugar’ Hill Keeps the Kronk Flame Burning in Banged-Up Detroit

Anthony Dirrell, who risks his WBC 168-pound world title against former title-holder David Benavidez this Saturday, Sept. 28, is one of the last of a dying breed, one of the last active fighters who earned his spurs at the fabled Kronk Gym, by which we mean the original Kronk Gym at 5555 McGraw Street on Detroit’s west side, the place that the late great trainer Emanuel Steward put on the map.

Steward, an electrician by trade and former National Golden Gloves champion, built an amateur boxing powerhouse in the basement of the Kronk Rec Center before attracting national notice for his work with Kronk alumni who turned pro, most notably Tommy Hearns. Anthony Dirrell and his older brother Andre Dirrell represented Kronk as amateurs. They learned their craft in the original gym, often with Emanuel Steward present, watching over them like a mother hen and giving pointers.

Steward always had assistants (in the beginning unpaid volunteers) and their roles became larger as Steward became the sport’s most prominent hired gun, taking him away from Detroit for long stretches to coach such notables as Lennox Lewis and Wladimir Klitschko, plus serving as a member of HBO’s boxing broadcasting team. The most prominent of the assistants were Johnathon Banks, who currently trains Gennady Golovkin, and Javan “Sugar” Hill who will be in Anthony Dirrell’s corner on Sept. 28, having trained both Dirrell brothers off and on since their amateur days.

Emanuel Steward died in 2012 after a short illness at age 68. By then the Kronk Rec Center, built in 1921 when the area around it was heavily Polish, was no more. As the economy of Detroit worsened – the city filed for bankruptcy in 2013 – instances of vandalism increased as desperate people took to stealing anything that could be sold on the black market. In September of 2006, thieves entered the rec center in the still of the night and disemboweled it, removing all the copper fixtures. With its budget strapped, the city couldn’t afford the cost of repairs. Six years later, most of the building was destroyed by a fire of suspicious origin. Last year, what was left of the structure was finally demolished.

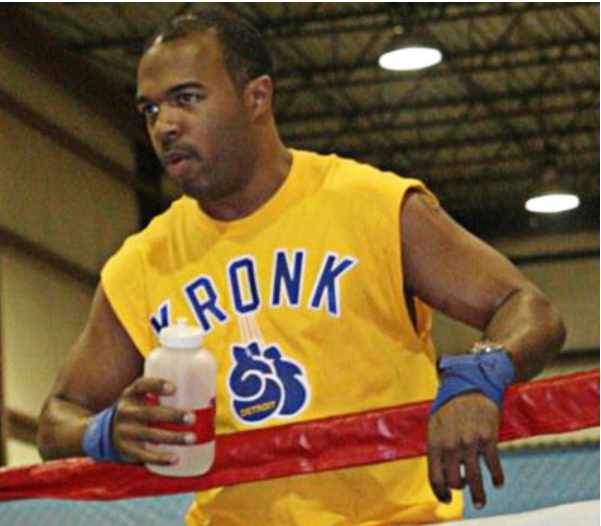

But the Kronk Gym, a hallowed name in boxing, never perished; just the place where Emanuel Steward worked his magic. The gym is currently housed in a former church, school and convent that has passed through several hands since being closed by the Catholic Archdiocese of Detroit. There you will find Javan “Sugar” Hill when he’s not out of town at an amateur boxing tournament or on the road with a professional fighter. The 48-year-old Hill, above all others, is the man keeping the Kronk flame burning.

It was inevitable that Javan Hill would take on this responsibility; he is Emanuel Steward’s nephew. “Emanuel was his parents only boy,” notes Javan, “and I am my parents only boy.” That common circumstance strengthened their tie. For much of his youth and into his adult years, Hill resided in Steward’s home.

Hill spent 12 years on the Detroit police force. In 2007 he took an early retirement so that he could focus more fully on the gym. “When I was growing up,” he says, “I never thought about becoming a policeman. For me, it was an opportunity to get off the street and keep myself out of trouble.” (With his uncle Emanuel looking after his welfare, it’s doubtful that Hill would have strayed too far from the straight and narrow, but we will take him at his word.)

When Emanuel Steward died, Wladimir Klitschko went with the aforementioned Banks as his new trainer. Hill wasn’t resentful – he and Banks are best buddies – although he had more longevity with Kronk.

“Johnathon had been with Emanuel at Klitschko’s training camps and he and Wladimir had developed a special relationship. I was less involved because of Adonis Stevenson. Adonis wasn’t yet a champion when Emanuel died and I had the satisfaction of helping him grow into a world champion.”

Stevenson suffered a traumatic brain injury in the 10th defense of his world title on Dec. 1 of last year when he was stopped in the 11th round by Oleksandr Gvozdyk.

How is he doing? “We talk quite a bit,” says Hill, “and he is making steady progress.”

Hill draws a comparison between Stevenson’s current situation and one of those old dial-up computers that took forever to download a song. But little by little, things are slowly getting back to speed for him. “He can’t drive yet, but he can communicate in French, English, or Creole,” Hills says of the ex-champion who was born in Haiti and grew up in Montreal.

In the heyday of Kronk, the program had a big booster in Coleman Young, the city’s five-term mayor whose 20-year reign began in 1974. Subsequent mayors have been far less supportive (understandable considering the budget constraints), making it that much harder to recapture the glory days anytime soon.

In his quest to make boxing relevant again in Detroit, Hill found an unlikely ally in Ukrainian-born Dmitriy Salita. A former world title challenger who retired with a record of 35-2-1, Salita launched Salita Promotions in his hometown of Brooklyn as his career was winding down. When the New York Athletic Commission effectively put him out of business by adopting more stringent insurance requirements, prohibitively expensive for a grass-roots promoter, Salita shifted his base to Detroit where he had trained for his last few pro fights.

Salita, 37, has made great strides as a promoter. His clients include Claressa Shields, Jarrell “Big Baby” Miller and Norway’s newest sporting hero, Otto Wallin. Salita has also roped in a number of promising prospects from Russia and her former satellites, the most arresting of whom is Uzbekistani knockout artist Shohjahon Ergashev (17-0, 15 KOs), currently ranked #6 at junior welterweight by the IBF. Ergashev trains at Kronk as do three fighters who appeared on the same card last week in Grozny, Russia: heavyweight Apti Davtaev, light heavyweight Umar Salamov, and super middleweight Aslambek Idigov.

The Eastern European contingent has introduced a new strain into Kronk’s inner city vibe. It’s also made life somewhat more challenging for Javan Hill, especially on those occasions when he is working a corner and has only 60 seconds before the start of the next round to convey the message he wants to convey. But, Hill insists, it hasn’t been as challenging as one might think.

“Boxing is a universal language,” he says. “All of our foreign fighters take classes in English.” Alexey Zubov, a 32-year-old Russian cruiserweight with a 17-2 record, speaks almost flawless English and is often there when a translator is needed.

Kronk Gym became something of a foster child when the rec center shut down. For a time, Kronk fighters trained in the Detroit suburb of Dearborn. The gym’s current home, at 9520 Mettetal, six miles away from where it all started, suits Javan Hill to a tee because the surroundings so closely mirror the original.

“We’re back in the basement again, just like the old days,” says Hill, “and in a place very much like a rec center. Upstairs there are programs for adults that teach certain skills. And I like the fact it’s a small gym, just like our old gym.”

In a big gym, notes Hill, it’s harder to know when someone is slacking off. When a boxer hits a heavy bag and does it correctly, it emits a certain sound. A good trainer in a gym where there’s a lot going on, knows how to keep tabs on things with his ears as well as his eyes. “Here,” he says, “I can hear everything going on.”

The boxers who work out at Kronk are as young as eight years old. When school is out, says Hill, there may be as many as 25 or 30 amateurs on the premises. Emanuel Steward, were he alive, wouldn’t have it any other way. Steward believed that if a gym had a strong amateur program, the professional side would evolve organically.

If boxing in Detroit never gets back to where it once was, it won’t be for lack of trying. And the man doing the heavy lifting is Javan “Sugar” Hill, Emanuel Steward’s nephew and surrogate son.

Anthony Dirrell

Anthony Dirrell (pictured below) turns 35 next month. His fight this coming Saturday with undefeated and heavily favored David Benavidez, 12 years his junior, may be his last rodeo. He has hinted at retirement.

It’s hard not to root for him as few fighters have overcome as much adversity. Born and raised in hardscrabble Flint, Michigan, Dirrell was diagnosed with non-Hodgkins lymphoma in December of 2006. He was out of action for 22 months while undergoing chemotherapy. In May of 2012, he broke his leg and fractured his arm in a motorcycle accident. That dictated another long layoff. But he persevered and on Aug 16, 2014, he won the WBC world 168-pound title with a unanimous decision over Sakio Bika in a rematch after their first encounter ended in a draw.

Dirrell lost the belt in his first defense on a close decision to Badou Jack, but regained it earlier this year at the expense of Turkey’s Avni Yildirin after the title became vacant when Benavidez was stripped of it for testing positive for cocaine. His fight with Yildirin was stopped by the ringside physician after 10 rounds because of a worsening cut caused when the fighters clashed heads three rounds earlier, sending the fight to the scorecards. It was a tougher-than-expected fight for Dirrell who prevailed on a split decision.

The bout between Dirrell (33-1-1, 24 KOs) and Benavidez (21-0, 18 KOs) is the chief undercard bout underneath the welterweight title unification fight between Errol Spence Jr. and Shawn Porter. It will air on FOX pay-per-view.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers