Featured Articles

The Life and Mysterious Death of World Title Challenger Eloy Perez

Eloy Perez had 27 pro fights and lost only one. That came in his final bout when he challenged Adrien Broner for the WBO world super featherweight title. The bout aired on HBO from the big hockey arena in St. Louis. Deontay Wilder and Keith Thurman appeared on the undercard.

A week ago, Oct. 11, Perez was found dead in Tijuana. When he was remanded to the Mexican border town, it was like being packed off to a foreign country. Perez was born in Mexico but came to the U.S. as a toddler. He wasn’t fluent in Spanish.

Eloy Perez grew up in Rochester, Washington, a place where there were relatively few people who identify as Hispanic or Latino. He grew up poor. The family lived in a trailer that was eventually moved to the property of Eloy’s boxing coach, Jim Douglas, who let the Perez family live there rent free. With the money they saved, Eloy’s parents were able to purchase a house in the neighboring town of Rainier where Eloy spent his last two years of high school.

The best way to become popular with the Anglo crowd was through the medium of sports and Eloy was very good at it. He excelled at soccer and as a running back on the football field although he stood only five-foot-five. Where he really excelled, however, was in boxing, a sport he took up at the age of 13.

The highlight of Perez’s amateur career came in an international tournament in Kansas City. There were 32 fighters in his weight class. Perez came out on top, defeating a 27-year-old man in the finals.

Cameron Dunkin, a scout for Bob Arum, was in attendance. Dunkin encouraged Arum to sign him, but Arum backed off, ostensibly because Perez was still in high school. In recent years, the Top Rank honcho has signed boxers as young as 16 to professional contracts, but back in those days Arum drew a harder line in the sand.

As an amateur, Perez could only go so far. The governing body of amateur boxing in the United States had a rule that once a boxer reached the age of 17, he had to prove citizenship. The process, from application to acceptance (or denial), was tedious. Pursuing it would have meant a substantial gap in Eloy Perez’s amateur timeline.

When Perez turned pro, he didn’t have to leave home. Rochester was home to an Indian casino, the Lucky Eagle, which ran club fights on a regular basis. The promoter and matchmaker there was none other than Bennie Georgino. (A fabled fight character in Los Angeles during the glory days of the Olympic Auditorium, Georgino, who died in 2016 at age 95, had managed or co-managed three world champions: Albert Davila, Jaime Garza, and Danny “Little Red” Lopez.)

There were very few pro boxers residing in the vicinity of the Lucky Eagle. Georgino filled his cards with fighters from California and Canada. Eloy Perez was a godsend. Georgino didn’t have to dip into his thin budget to feed him or pay his travel expenses. More importantly, Eloy was a big draw right out of the box. For a grassroots promoter, there is no commodity more prized than a hometown hero.

Perez was a junior in high school when he made his pro debut. To be on the safe side, Georgino made him fudge his I.D., making a year older than his actual age.

At this early stage of his career, boxing didn’t pay the bills. Perez took a job working at a warehouse owned by the Fred Meyer company, the operator of a chain of Walmart-like stores in the Northwest. It was there that he had his first brush with the law.

Security caught him leaving work with a packet of batteries in his pocket, an $11 item, and turned him over to the police. He pled guilty to a charge of third-degree theft, receiving a fine and a suspended sentence.

There came a day when Perez had to fly the coop, go somewhere where he could refine his skills with world-class trainers and good sparring partners. He hooked up with Max Garcia, a prominent Northern California trainer and small-time promoter whose base was in Salinas. Garcia had good contacts and it wasn’t long before Eloy was fighting under Oscar De La Hoya’s Golden Boy umbrella.

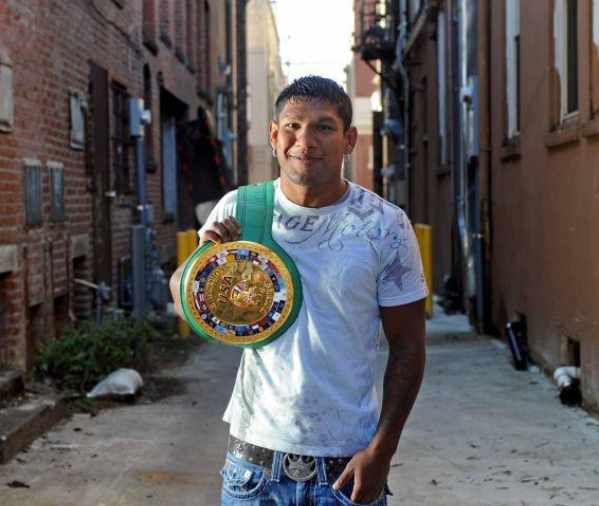

In September of 2009, Perez won a regional belt with a 10-round decision over fellow unbeaten Dannie Williams at the Playboy Club in Beverly Hills. (The photo shows Perez displaying the belt shortly after winning the fight.) He was 23-0-2 with 1 NC entering his title fight with Adrien Broner and riding a 15-fight winning streak.

Broner was too quick for him. In the fourth round of the one-sided fight, Perez was knocked down and the referee waived it off as Eloy was struggling to get back on his feet.

Things got worse for him. His post-fight urine test revealed the presence of cocaine. His California handlers were so disgusted they wanted nothing more to do with him. With only one defeat blemishing his record, it would seem that Eloy Perez had a lot of boxing left in him, that maybe he could claw his way back to another title fight, but he would never fight again. He drifted back to the state of Washington and got in more trouble.

His second arrest for driving while intoxicated landed him at an immigrant detention center in Tacoma where he languished for more than a year. Purportedly given the choice of prison or deportation, he chose the latter so that his girlfriend in California could visit him unfettered by prison constraints. ICE dumped him in Tijuana.

The authorities say that Eloy Perez took his own life. His sister Emma will never believe it. She is certain that he was murdered.

Her theory is actually more plausible. Back in the days of Prohibition and even before, Tijuana was a popular playground for American tourists looking to let their hair down. In those days, words like “dusty” and “sleepy” were invariably used in descriptions of Tijuana by travel writers.

That place doesn’t exist anymore. Tijuana has grown into a city of nearly 2 million people, many of whom migrated here from other parts of Mexico. It is also one of the most violence-plagued places on the planet. In 2018 there were 2,519 homicides, the highest number per capita of any city in the world, the bulk of it attributed to turf wars between low-level drug dealers.

It’s likely that the true cause of Eloy Perez’s death will never be known. Whatever the cause, these bare facts won’t change: He was a high school sports hero in a small town in Washington, was a professional boxer good enough to fight for a world title, had legal problems that caused him to be evicted from the country where he had resided since he was scarcely old enough to walk, and he drew his last breath in Tijuana.

Upon learning of his death, fight publicist Rachel Charles wrote that Perez might be one of the greatest “what if” stories in boxing. There are a whole lot of “what ifs” here.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons