Featured Articles

Boxing’s Thrill Factory: Then and Now

Boxing’s Thrill Factory: Then and Now

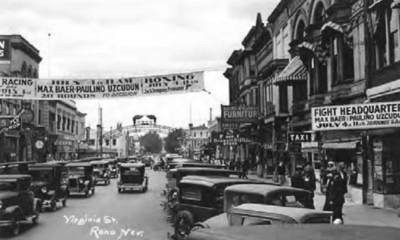

Through the years — going back even before Jack Dempsey — some fighters included maximum aggression and violence in their repertoire. Max Baer’s contribution was manifested in his lethal right hand. Later, Chicagoan Bob Satterfield had a “get you or be gotten” style that tingled spines whenever he fought. It was chill-or-be-chilled and the fans loved it.

Charley Norkus and Danny Nardico possessed paralyzing power. When they met, they produced an incredible, although predictable, bloodbath—a ruthless, wild, pier six brawl yielding eight knockdowns and full-tilt boogie violence. Nardico went down six times and Norkus twice before the “Bayonne Bomber” was finally able to put away Nardico in the ninth with jackhammer blows. Only the first Moore vs Durelle fight could match this, though Foreman vs Lyle in 1976 came close.

Speaking of full-tilt boogie, Boom Boom Mancini and Art Frias gave the phrase new meaning when they engaged non-stop in less than one round in 1982. One would not give it up; the other wanted it, no matter what. David Tua and “The President” Ike Ibeabuchi did this for 12 amazing rounds in 1997. Holyfield and Bowe did it three times in the 90s.

Matthew Saad Muhammad and Indian Yaqui Lopez went to the brink, perhaps in a way that has yet to be matched. Danny “Little Red” Lopez was Saad before Saad and Gatti before Gatti.

Rocky Marciano, Tony Zale, Rocky Graziano, Carmen Basilio (pictured in his second fight with Sugar Ray Robinson), Gene Fullmer and Tony DeMarco were ultra-aggressive and later Jerry Quarry, Julio Gonzalez, Ricky Hatton, and Julian Letterlough picked up the mantle. Latinos Michael Carbajal, Humberto Gonzalez, Erik Morales, Marco Antonio Barrera, Miguel Cotto, Johnny Tapia and Juan Manuel Marquez ran with it.

God knows, “Iron” Mike Tyson became the poster child for this, but Tony Ayala Jr. also made his mark. He was not beyond spitting on an opponent he had decked. Tony was bad Ju Ju. If Tyson was the heavyweight version of someone who brought the heat, then most assuredly Arturo Gatti and Irish Micky Ward were the lower weight versions. Of course, Hearns and Hagler kept things very hot in the middleweight class as did Gerald McClellan who was pure aggression at its most violent level.

Sugar Ray Leonard’s baby face belied a ring assassin who, once he had his man stunned, would finish matters with stunning closure.

Nigel Benn, Michael Watson, Chris Eubank, Carl Froch in the UK and Michael Katsidis in Australia carried forth with this “Bring the Heat” style but it proved nearly fatal for Watson and cost Katsidis in the end. Earlier, it cost the relentless Bobby Chacon terribly. Julio Chavez Sr. and Roberto Duran were both savage stalk-and-destroy types. The excitement their battles produced was truly memorable.

‘It was a tough fight, but that’s the way I like to win them … I said I was going to introduce new blood to the sport, and I guess you saw a lot of new blood.” —Michael Katsidis

Female great Holly Holm, active from 2002 to 2013, was just vulnerable enough to provide plenty of thrills. Lucia Rijker, in contrast, was probably too good for her own good, and dominated during a boxing career that ran from 1996-2004. Christy Martin is considered to have legitimized women’s participation in the sport of boxing during her thrilling run between 1989 and 2012. All things considered, she was the ultimate thrill provider.

Something or some combination of things set these boxers apart from the rest. None refused to stay down; some had to be saved by their corner. None had quit in their DNA. All had doggedness, tenacity, and a persistent determination to beat their opponent no matter what it took. Unfortunately, for some it took too much, for they did this with a total disregard for their wellbeing.

“A Quarry never backs up.” —Jack Quarry

There were many, many others but space does not allow for their inclusion.

Today’s Thrill Factory

Deontay Wilder has gotten to the point where the outcome of his fights is predicated on “when,” not “if.” His KO power is such that the “when” can come at any time. While his style leaves much to be desired, the one-punch power is what thrills fans. The “Bronze Bomber” is dangerous until the last second of the fight.

Dillian Whyte enjoys his reputation as someone who brings the heat and his results back up his boasts. He says, “…this is my time now. Crack another skull and get closer to fighting for a world title… I come with maximum violence.”

Adam Kownacki keeps on winning with a no back-up style that has his Polish fans in Brooklyn up and roaring throughout his fights. He’s not pretty but he’s 20-0.

Andy Ruiz has always been a guy who breaks his opponent down, but his atypical and explosive ambush of Anthony Joshua suggests he could be another worthy spine-tingler. The rematch will tell us what we need to know.

Light heavyweight Artur Beterbiev brings a heavy-handed excitement with his bludgeon-like power and deceptive technical skills.

Gennady Golovkin continues to be pure excitement, but now that he’s on the downward slope of his great career, the “if” has become equal with the “when.” He arguably has become a more modern version of the great Kostya Tszyu.

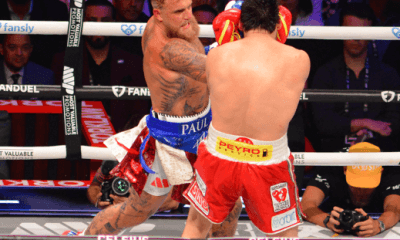

Manny Pacquiao has always been super-thrilling but his loss of KO power in recent years has taken much of the edge off. Nevertheless, when he fights it’s an event that draws massive attention much like Canelo today and Oscar De La Hoya in the past.

Terence Crawford’s ability to adjust and then close the show makes him compelling, but not necessarily more thrilling than other welterweights. The division is a hot one—as is the junior welterweight division with Josh Taylor and Regis Prograis leading another bunch of exciting fighters.

Vasiliy Lomachenko provides thrills with the unique things he does in the ring, reflecting his legendary amateur career and his “Hi-Tech” training. Teófimo Lopez has the potential to be included in today’s thrill house.

Gervonta “Tank” Davis is a modern-day prototype of an aggressive and violent fighter. He likely will move up in weight, leaving rugged Miguel Berchelt to remain king of an exceptional division

Naoya “Monster” Inoue has the right nickname but his showing against an aroused Nonito Donaire showed that he is human after all and that makes him even more exciting. “Monster” is today’s best example for inclusion in the Thrill Factory.

Nicaragua’s Roman Gonzalez used to be one of the most exciting fighters, but Father Time caught up with him. Filipino Donnie Nietes is a superb technical fighter, but not an exciting one, while Japan’s Kazuto Ioka, Mexico’s Juan Francisco Estrada and Thailand’s Srisaket Sor Rungvisai are the opposite. The junior bantamweight division is loaded.

And lest we forget, the exciting Saul “Canelo” Alvarez, who has become boxing’s greatest attraction, continues to surge, finishing the decade with two grueling fights with Gennady Golovkin and a savage KO over Sergey Kovalev. His KOs of Baldomir, Kirkland, Khan, and Kovalev were frightening in their ferocity and finality.

While today’s boxing offers plenty of thrills, the facts suggest that the house of thrills and excitement is not nearly as full as it could be. There are plenty of potential occupants, particularly from Japan, Mexico and Eastern Europe, but they have yet to fully emerge.

Back in the day, you could throw a dart. It’s not like that today.

Or is it?

Ted Sares can be reached at tedsares@roadrunner.com

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Shafting of Blair “The Flair” Cobbs, a Familiar Thread in the Cruelest Sport

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden