Featured Articles

Tom Molineaux and the Mule Faced Boy: Deconstructing Slave Fight Folklore

Tom Molineaux and the Mule Faced Boy: Deconstructing Slave Fight Folklore

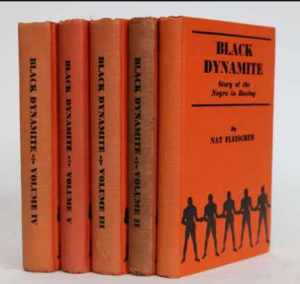

February is black history month in the United States and Canada, a tradition that dates to the 1970s. Nat Fleischer, the co-founder and publisher of The Ring magazine, was ahead of the curve. Fleischer authored Black Dynamite, a five-volume series released in 1938 that celebrated the achievements of black boxers in the prize ring.

Black Dynamite was seminal, especially Volume 1 which covered the bare-knuckle era. Post-1938, most of what would be written about antiquarian black prizefighters was culled from Fleischer. The challenge now for modern day boxing historians is to figure out how much of what he wrote is actually true. The inconvenient truth is that a lot of rubbish was published under Nat Fleischer’s byline.

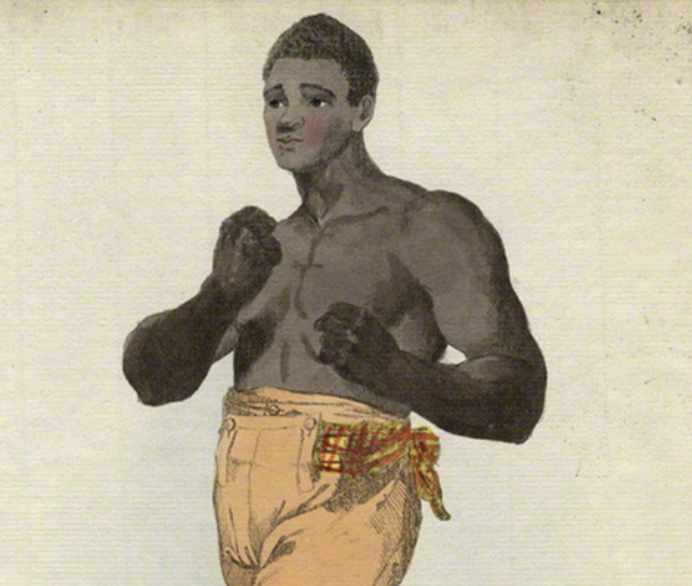

Vol. 1 is rich in information about Tom Molineaux. An American slave by birth, Molineaux turned up in England about 1809 and after a few minor bouts succeeded in landing a fight with England’s topmost fighter Tom Cribb. They actually fought twice, first in December of 1810 and then again in September of 1811. In their first encounter, Molineaux was cheated of victory when a mob burst through the ropes and bullied the referee into giving Cribb extra time to recuperate when he was just about finished. In the rematch, contested without incident, Molineaux was knocked out.

The various retellings of these two fights differ in little details, but what is indisputable is that these fights, although ignored by the American press, gripped men of all social classes in England, notwithstanding the fact that prizefighting was a bootleg sport with matches necessarily held outside densely populated areas. Tom Cribb was recognized as the champion of England, tantamount to being the champion of the world, and it was a matter of considerable importance to the Brits that he did not yield his title to a foreigner, especially a black foreigner. His victory over Molineaux in their rematch inspired a great outpouring of affection. When he died, his admirers commissioned a handsome stone statue of a lion to ornament his tomb.

The dates and results of Molineaux’s prizefights in England are a matter of public record. But what about Molineaux’s background? And how, pray tell, did he get from point A to point B, how did he shake free of the shackles of slavery in the United States and wind up becoming one of the most famous pugilists in all of Great Britain?

Fleischer doesn’t identify his sources, but says that through arduous research he learned that Tom Molineaux was born into a family of great bare-knuckle fighters. His father Zachary and Tom’s brothers Elizah, Ebenezer, Franklin, and Moses were also renowned pugilists “and they outclassed all rivals in Virginia.”

Tom earned his freedom from bondage, says Fleischer, by defeating a slave from a rival planation. Tom’s master, Squire Algernon Molineaux (all of his slaves took his surname) was one of the wealthiest men in Virginia and wagered such an immense sum that he faced bankruptcy if Tom was defeated. Manumission was Tom’s reward.

On the subject of slave fights in general, Fleischer says, “Tournaments were held to determine which slave was plantation champion and, inevitably, these rivalries soon transcended plantation boundaries…The slaves (in inter-plantation fights with huge sums at risk) fought and trained on a reward-punishment basis, the best of their lot being excused from the gruesome field work and perhaps even gaining their freedom while the less talented might be denied food for several days or even put to death for an inept performance.”

Nat Fleischer’s credibility as a boxing historian was such that his rendering came to be accepted as gospel. The lurid 1957 best-seller Mandingo, the debut novel of the shameless Falconhurst series, calcified Fleischer’s perspective,

Falconhurst is the name that author Kyle Onstott gave to the antebellum plantation where his story was centered, a place where incest and miscegenation were rife and slaves were hideously dehumanized, even mutilated and murdered. And yes, brutal slave fights factor into the narrative.

The novel Mandingo spawned the 1975 movie of the same name and its sequel Drum, movies in which Ken Norton played a prominent role. Quentin Tarantino’s 2012 blaxploitation Western Django Unchained pays homage to Mandingo. A bare-knuckle fight to the death between two black slaves is a key plot point in the movie. Fights of this description would acquire the name Mandingo fights.

Tarantino’s movie heightened interest in slave fights, reviving the question of whether Mandingo fights actually happened. And by now, educators well-versed in African-American history could see that fights of this nature just didn’t pass the smell test.

A male slave had value to a plantation owner as a field worker and as a breeding mechanism and, like all his slaves, was property he could pass on to his heirs or sell if times got tough. A slave with the strength and stamina to become a champion prizefighter would logically be especially valuable. To risk a man of this caliber in a fight where he stood the risk of being severely damaged, makes no sense economically. It would be akin to a luxury car dealer entering his most expensive vehicle in a demolition derby.

There are a few first-person accounts of organized matches among slaves (I am aware of only two), but in no way do they resemble the battle in which Tom Molineux purportedly won his freedom. Betting on horse races was a popular pastime among Southern planters, but old newspapers contain no reports of inter-plantation prize fights and if it were true that life-changing sums were actually being bet on these competitions, they would have almost certainly attracted notice.

After winning his freedom, says Fleischer, Molineaux found his way to Baltimore where he found work as a stevedore on the docks. He then hired out as a deckhand on a boat to Liverpool. “The seas were rough,” says Fleischer, “and at times it appeared the vessel was about to take a dive into Davey Jones locker.”

The best boxing gyms were then in London. The sport’s wealthiest backers were also found there. So, Tom hied his way to London, trudging off on foot, says Fleischer, late in the winter of 1809 when the weather was inconducive to walking. He arrived penniless and hungry.

Wow, that was some walk, and in inclement weather no less. If one were driving from Liverpool to London, one would travel 220 miles.

The Mule Faced Boy

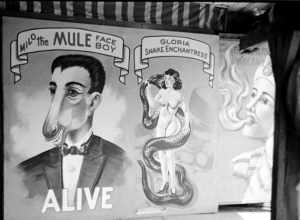

Many years ago, when I was in my early teens, I chanced upon Milo the Mule Faced Boy on a visit to Coney Island. More exactly, I chanced upon the gaudy mural on which he was depicted, the come-on that enticed passersby into the freak show where he was appearing. The commercial display of people with physical abnormalities came to be seen as exploitive, if not downright creepy, but it hadn’t yet run its course as a popular amusement.

In person, Milo, who appeared to be a man in his mid-20’s, didn’t look anything like the caricature of him on the mural outside. There was some misshapenness there, but I wouldn’t have drawn the correlation to a mule if it hadn’t already been stamped in my mind.

Milo made a short talk – or maybe it was the spieler who did all the talking; my memory is fuzzy – and the show, as it were, concluded with an exhortation to purchase his biography, a cheap little pamphlet that was within my limited means and so I bought it.

My goodness, what an exciting life Milo had led. It was a life chock full of harrowing adventures reminiscent of the Saturday matinee serials that inspired filmmaker George Lucas to create the Indiana Jones franchise.

That cheap souvenir is long gone. My mother likely tossed it away with my baseball cards and other clutter left behind when I went off to college. It is what mothers do, bless their souls. But I have come to learn that these flimsy biographies were standard fare for freaks that worked the fair circuit or appeared in so-called dime museums and that these little storybooks shared a common scaffolding, differing only in the details. They weren’t all written by the same person, but whoever got the ball rolling set the template and subsequent generations of ghostwriters adhered to the formula.

– – –

Tom Molineaux fought sporadically after his second match with Tom Cribb. He died in Ireland in 1818 at age 34.

In the last years of his life, Tom worked the fair circuit in the British Isles, giving exhibitions and undoubtedly regaling his audiences with a little talk about his escapades. His traveling companions would have been other freaks, both organic such as giants and dwarfs and self-made such as snake charmers and sword swallowers. He would have had a little biography for sale.

Take away all the embellishments and the saga of Tom Molineaux is still a remarkable story, but the embellishments have distorted the truth to where the real flesh-and-blood Tom Molineux is lost in the rubble of history. Brian Phillips, writing for Grantland in 2012, had it right when he wrote that if you were to look up Molineaux in an encyclopedia, “what you’ll find is less an authoritative account of the facts than two centuries worth of distilled legend.”

Molineaux was obviously a brave and resourceful man, a man with an adventurous spirit who led an incredibly exciting life. But that bit about his kinfolk — his father Zachary and his brothers, all bare-knuckle fighters of great renown – and the bit about the fabulous sums wagered on inter-plantation slave fights, why that’s all hokum, fictions born in the fertile imagination of a hired pen freelancing as a circus pitchman.

Can I prove it? No. But of this, I am quite certain.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

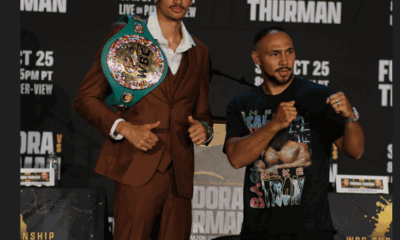

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More