Featured Articles

Tyson Fury Goes on the Offensive For Rematch With Wilder

Tyson Fury Goes on the Offensive For Rematch With Wilder

It has been said that a kangaroo is a horse designed by a committee, but nature tends to work best when a horse doesn’t try to be anything but a horse and a kangaroo happily remains a kangaroo. But that doesn’t stop the experimenters among us, always looking to modify what was or is, from fiddling with the status quo in an effort to produce a new and hopefully superior version of something.

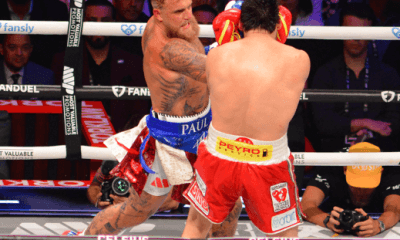

When lineal heavyweight champion Tyson Fury (29-0-1, 20 KOs) enters the ring for his rematch with WBC titlist Deontay Wilder (42-0-1, 41 KOs) on Feb. 22 at Las Vegas’ MGM Grand, he won’t exactly be a patchwork kangaroo with a few residual equine traits. Nor will he have three trainers, all of whom have had their turn constructing the “Gypsy King” to their preferred specifications, working his corner that night. The last of that trio of chief seconds is recently hired Javan “Sugar” Hill, nephew of the late, great overseer of Detroit’s legendary Kronk Gym, Emanuel Steward. Manny, a 1996 inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame who was 68 when he died in 2012, was like a pass-happy offensive coordinator in football, as are his disciples, all partial to high-scoring contests in which their guy wins by making more splashy big plays (think knockdowns and impressive displays of power-punching) than whomever is working the other sideline and playing D.

There are two ways, and two ways only, to win any athletic contest or boxing match. One is to score more than the other side; the other is to allow the other side to score less than you do. Those objectives might sound the same, but they are fundamentally worlds apart. Rare is the team or fighter equally adept at mastering both strategies and employing them interchangeably.

Hill takes the place of the more defense-oriented Ben Davison, jettisoned after his most recent outing as Fury’s coach du jour, a unanimous but nonetheless worrisome decision over Sweden’s Otto Wallin on Sept. 14, 2019, at the MGM Grand, a bout in which Fury incurred an ugly gash over his right eye that required 47 total stitches to close. It would not have been a travesty of justice had referee Tony Weeks or the ring physician stopped the fight at some point in the later rounds and awarded the underdog Scandinavian southpaw a shocking upset victory.

“I had a good defensive coach in Ben Davison,” Fury, who also will have a new cut man, “Stitch” Duran, noted of the young trainer who took the place of his original trainer and uncle, Peter Fury, who also was determined to be lacking in some way. “We worked a lot on defense every single day for two years. It was defense, defense, defense.

“But I needed an aggressive trainer. I worked with Sugar Hill in the past. I knew he was a good guy. I knew we got on well, which was very important. Communication is key to any relationship. That’s why I brought him in. It was one of the best decisions I ever made.”

Now that he is better acquainted with the attacking Kronk methods passed on by Steward to Hill and some of his other assistants, it is little wonder that the 31-year-old Fury is uncharacteristically predicting a second-round knockout of Wilder, whose modus operandi is always the same: throw right-hand bombs -until one connects and dude laying on the canvas has been counted out. If you want to call the “Bronze Bomber” from Tuscaloosa, Ala., a one-trick pony, that’s all right. He knows who and what he is, and he makes no apologies for unalterably adhering to the singular principle that has made him one of the hardest-hitting heavyweights of all time, and arguably the biggest bopper ever, according to Top Rank founder and CEO Bob Arum, who promotes Fury. You wouldn’t think Arum would approve of Fury, a clearly more polished boxer, choosing to slug it out with Wilder in the center of the ring, but, as always, there are different paths to victory. The best fight plan indisputably is whichever one works.

“I have confidence in Tyson,” Arum said of his new-look heavyweight headliner. “There are guys who say they’re going to knock out their opponent, but it’s like a baseball player getting up to the plate and trying to hit a home run. Anybody who knows baseball will say that the guy who looks to make contact has a better chance to hit a home run than the guy that’s swinging from his heels.”

A let-’er-fly guy like Wilder, in other words.

“Tyson is a great boxer, but he has the determination to knock out Wilder,” Arum continued. “He’s not going to force it, but the knockout will come. Unlike the first fight, when he got Wilder into trouble – and Wilder was in trouble a couple of times – he’s not going to let him off the hook.”

To Fury’s way of thinking, the huge Briton – when you’re 6-foot-9 and 254½ pounds, as the badly bleeding Gypsy King was for his excursion into the danger zone against Wallin – the only certainty of outcome is when the winner snatches the pencils out of the judges’ hands. In their first clash, on Dec. 1, 2018, in Los Angeles’ Staples Center, Fury was floored twice, a flash knockdown in the ninth round and something far more perilous in the 12th and final round, but he barely beat referee Jack Reiss’ count and somehow managed to stay upright for more than two minutes until the final bell.

The outcome – a split draw – satisfied neither Wilder, who figured two knockdowns should have given him the edge, nor Fury, who seemingly stockpiled most of the non-knockdown rounds as a squirrel might horde acorns for the winter. The tabulations read 115-111 for Wilder on Alejandro Rochin’s scorecard, 114-112 for Fury on Robert Tapper’s, and 113-113 on the one submitted by swing judge Phil Edwards.

“I didn’t get the decision because I didn’t keep working on my boxing,” Fury said. “I believe I can outbox Deontay Wilder very comfortable, but the fact of the matter is I outboxed him very comfortable the last time. But it’s no good me believing it; the judges have to believe it. To guarantee victory, I’ve got to get a knockout. I don’t want another controversial decision.

“Look, I’m not a judge. They see what they see. That’s what they get paid to do. This time my destiny lies in my own two fists.”

But what of the presumed imbalance of power? What if Wilder really does wield the biggest hammer in heavyweight history? Won’t going toe-to-toe with him be like engaging Babe Ruth in home run derby or Michael Jordan in a slam-dunk competition?

“That was one of my easiest fights,” Fury said of his first go at Wilder. “Other than the two knockdowns it was a pretty much one-sided fight. I’ve had fights much harder than that. My toughest opponent was Steve Cunningham, the former cruiserweight champion (who decked Fury in the second round of their April 20, 2013, bout in New York before finally succumbing on a seventh-round stoppage). It was my first step up to anybody with that type of ability. He was slick and hard to hit, awkward but a very good boxer.”

It is Fury’s contention that his various trainers have supplied him with the versatility to enter the lion’s den and emerge relatively unscathed, while Wilder lacks the imagination and ability to go to a Plan B, if indeed he has one.

“I think there’s nothing to worry about,” Fury said of what he expects from Wilder. “He’s got a big right hand and that’s it. He’s a one-dimensional fighter. The one who should be concerned is Deontay Wilder. He had me down twice, but he couldn’t finish me. He landed the two best punches any heavyweight in the world could ever land on somebody else and the Gypsy King rose, like a phoenix, from the ashes.

“I’m match-fit, I’m ready, I’m confident, I’m injury-free. I’m ready for a war, one round or 12. And when I get him hurt, I’ll throw everything but the kitchen sink at him. He won’t know what hit him.”

Maybe. But if another stylistic makeover on short notice doesn’t yield the desired result, Tyson Fury could wind up looking like the horse that tried to be a kangaroo.

Wilder-Fury II can be accessed via ESPN+ and Fox Pay-Per-View. The suggested list price is $79.99.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Shafting of Blair “The Flair” Cobbs, a Familiar Thread in the Cruelest Sport

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden