Featured Articles

132,000-Plus….A Boxing Attendance Record Unlikely to Ever be Broken

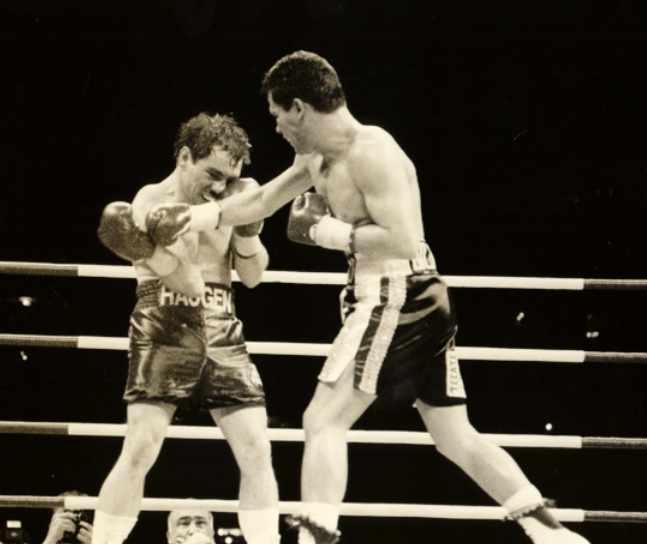

You always hear that records are meant to be broken, but, barring a stunning change in national policy by a Communist country unwelcoming to outsiders, the 132,000-plus that turned out to see Julio Cesar Chavez pummel Greg Haugen on Feb. 20 1993, at Mexico City’s Estadio Azteca likely will forever stand first for live attendance for a boxing event.

Chavez’s intentionally cruel thrashing of the lippy Haugen enabled the Mexican national hero variously known as “JC Superstar” and El Gran Campeon to successfully defend his WBC super lightweight title for the 10th time. That fight was the capper to an incredibly deep card dubbed the “Grand Slam of Boxing” by promoter Don King, which also featured title retentions by such top-shelf attractions as Azumah Nelson, Terry Norris and Michael Nunn. But make no mistake, those outstanding fighters – Nelson and Norris, like Chavez, have been inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – merely served as fillers until the main event. The massive crowd might have been nearly as large and boisterous had the only scheduled bout been the white-hatted Chavez vs. Haugen, the presumptive American villain.

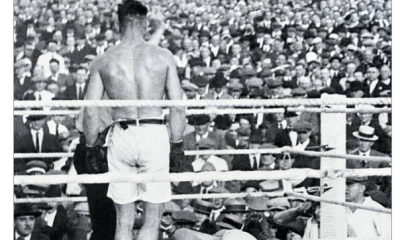

The announced attendance of 132,247 for a showdown fast approaching its 27th anniversary shattered the previous high for a boxing event, the 120,470 that filled Philadelphia’s Sesquicentennial Stadium on Sept. 23, 1926, to see Gene Tunney lift Jack Dempsey’s heavyweight title on a 10-round unanimous decision. (A crowd estimated at 135,000 turned up in a public park in Milwaukee to see Tony Zale fight Billy Pryor on Aug. 16, 1941, but that doesn’t count as there was bleacher seating for only a few thousand and the event was free for everyone.)

The recent incidence of stadium bouts with impressively large gatherings – 90,000 jammed London’s Wembley Stadium on April 29, 2017, to watch Great Britain’s Anthony Joshua retain his WBA and IBF heavyweight titles on an 11th-round TKO of long-reigning previous champion Wladimir Klitschko – hints at more large throngs willing to leave the comfort of their living rooms to see live boxing, but no promoter can fit a gallon into a quart bottle. Live attendance at least partially hinges on how much space there is in a place, and there is only one stadium that presently has a seating capacity larger than that of Estadio Azteca in 1993. That would be Rungrado 1st of May Stadium in Pyongyang, North Korea, which has a capacity of 150,000. But that huge facility is used primarily as a means of the country’s populace dutifully assembling for the purpose of feeding the ego of dictator Kim Jong Un.

It’s a sharp drop from Rungrado 1st of May Stadium to the 110,000-seat capacity of Sardar Patel Gujarat Stadium in India, known mostly as a cricket venue, and the 107,601-seat Michigan Stadium, the “Big House” of college football in the United States. Sesquicentennial Stadium (later known as John F. Kennedy Stadium) was demolished in 1992, and even Estadio Azteca, which was erected to host the soccer matches at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, has been downsized, having undergone renovations in 1999, 2013 and 2016. It now lists a capacity of “only” 87,523.

All of which likely stamps Chavez-Haugen as a pugilistic equivalent to Woodstock as a you-had-to-be-there human magnet in the estimation of renowned ring announcer Jimmy Lennon Jr., whose memories of the literally biggest event he ever worked are as vivid now as they were then.

“I can’t remember if they had large projection screens like they do now, but I’m assuming they didn’t have them then,” recalled Lennon, who joined referee Joe Cortez in sharing their recollections for this story. “Here you had this vast sea of people. I saw these little fires high up in the stands. People brought their own food and were cooking way up in the more distant seats. I remember thinking this was more of a mass celebration than just a sporting event. Whether or not a lot of people could really see much down in the ring, it certainly seemed that they were enjoying themselves. It was kind of like the huge crowd for Woodstock; just being there was a huge part of it.”

Cortez, now 76 and retired from refereeing, said he also was amazed by the gargantuan crowd.

“Walking into the stadium that day was like walking into a different world,” he said. “You had to be there to believe it, an event with that many fans, almost all of them rooting for Chavez.

“When Chavez was making his walk to the ring, the cheers were so incredibly loud I almost had to cover my ears, and the boos for Haugen when he was making his walk to the ring were just about as loud. It was an intense feeling, I think, for everybody. I knew it was for me. I never had been in a situation like that. I remember thinking, `What the hell can the people in the seats farthest away from the ring see, unless they have binoculars? The fighters must have seemed like two little ants, with me the third ant, in a tiny box. I knew then it was going to be an experience I would remember the rest of my life, and I still feel that way.”

Even though Chavez was and is the most popular Mexican fighter ever, the scene might not have been so incredibly jam-packed or emotional were not for the opponent. The ill will Chavez harbored toward Haugen, a onetime “Tough Man” contestant who had risen above those humble circumstances to win titles at both lightweight and super lightweight, was palpable, and had been simmering for three years. Each new affront by Haugen only served to harden JCC’s determination to someday make him pay.

The feud began behind closed doors, when Haugen showed up at a Chavez sparring session. As Chavez left the ring, Haugen approached him and sneeringly said that his sparring partners were “nothing but young little girls with dresses on.”

“I hated him from that moment on,” Chavez would later say, with Haugen seemingly enjoying any occasion by which he could verbally torment a fighter who the trash-talking antagonist knew would represent his biggest payday.

The stakes were raised on Dec. 13, 1992, moments after Chavez had scored a sixth-round TKO of Marty Jakubowski at The Mirage in Las Vegas. Haugen entered the ring and again confronted Chavez, telling him that his 84-0, with 72 wins inside the distance, had been crafted against “Tijuana taxi drivers that my mom could whip.” But this insult was heard on television, a flung gauntlet that Chavez was only too glad to pick up. He would make Haugen, who came in 32-4-1 with 16 KO victories, regret such impudence.

“I will not have mercy on you,” Chavez told Haugen. “I will rip your head off.”

King immediately realized that this fight called for the biggest possible setting, and what could be bigger than Estadio Azteca? His Hairness played up the revenge angle to the hilt, which was to be expected, except that it wasn’t standard pre-fight hype this time. Chavez, who was known to inflict as much pain as possible on any opponent who did not pay him his due as a great fighter, was on a mission to hurt and humiliate Haugen more so than anyone he had faced. There is little doubt that Chavez’s making the bout personal imbued his many supporters with the determination to be there so they could someday regale their children and grandchildren with the tale of how they witnessed their glorious knight slay the impudent dragon.

“I arrived very early at the stadium, maybe 1 p.m. or 1:30,” Lennon recalled. “I was in my tuxedo and practicing my announcements, but even then, maybe nine hours before the main event went on, there had to be 15,000 people in the stands. They were cheering as I practiced my introduction of Chavez. It’s always kind of awkward to practice your introductions in an empty arena, but it sure wasn’t empty then. Of course, all 132,000 hadn’t shown up either.”

Cortez, as was the case with almost everyone there except the few hardy souls who had come to support Haugen, figured Chavez to win. But what if the brash underdog from Washington state pulled off the upset that could spoil the festive mood of all those JCC supporters?

“The security was unbelievable,” Cortez said. “There were so many police officers and military people with their plastic shields, and a lot of them had German Shepherds on leashes. If a riot broke out, which nobody wanted, the security people were ready, but how ready could they have been with a crowd that big?”

Fortunately for all concerned, maybe even Haugen, the hordes of Chavez fans who had come anticipating another sterling performance by their hero got it, which enabled all of them to go home happy. Chavez dropped Haugen with an overhand right just 25 seconds into the first round, the first time the challenger had been decked as a pro, and he might have finished him off shortly thereafter had he pressed the issue. But Chavez eased his foot off the gas pedal, the better to do what he had vowed to do, which was to prolong the pain he was so intent on dishing out. That plan must have been obvious to everyone, even to the folks in the nosebleed section who paid only 5,000 pesos for their bargain tickets, then the equivalent of about $1.65 U.S.

“He has no way to keep Julio Cesar Chavez off, except mercy on the part of Chavez, and he has none,” TV commentator Ferdie Pacheco said of the systematic disassembly of a fighter who had no chance of winning but was too proud and determined to quit.

“I remember the way Chavez punished Haugen to the body instead of getting him out of there quickly,” Lennon said. “But that was the way Chavez was. You had the sense he was controlling every moment of the fight and could have ended it whenever he wanted to.”

Finally, after an elapsed time of 2 minutes, 2 seconds in the fifth, Chavez decided Haugen had had enough. Or maybe it was the compassionate Cortez who chose to intervene, wrapping his arms around the valiant but thoroughly beaten-up American.

Asked what he thought about all those “Tijuana taxi drivers” who he had characterized as Chavez victims, Haugen said, “They must have been very tough taxi drivers.”

No fight is made memorable solely by the number of butts occupying the seats. Upon reflection, Chavez vs. Haugen was utter domination of a good fighter by a clearly superior one. There have been many of those in the annals of the sport. But still …

“That is definitely one fight I won’t forget,” Lennon said. “When people ask me about the most memorable fights I’ve done, that one is right up there. If it isn’t No. 1, it’s pretty close, if only for the size of the crowd.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend