Featured Articles

Wilder vs. Fury: What History Tells Us About the Boxer and the Puncher

Wilder vs. Fury: What History Tells Us About the Boxer and the Puncher

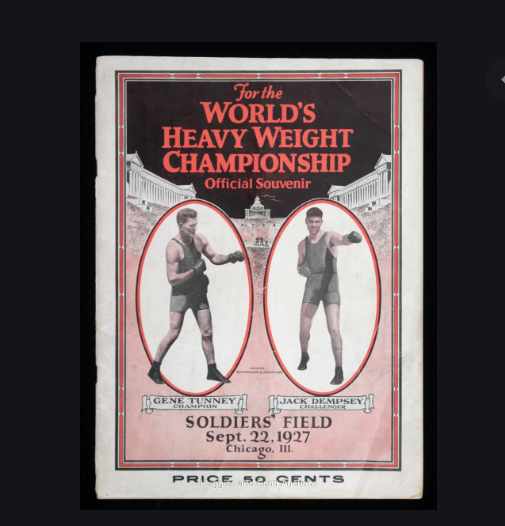

Jack Dempsey was “so badly out-boxed and out-classed” according to pre-eminent newspaper man Damon Runyon “he seemed more of a third-rater than one of the greatest champions that ever lived.”

“Gene Tunney is the best man I ever fought,” said Dempsey himself. “But if we ever meet again, I’ll beat him. There’s no maybe about that, either. He’s a grand man and a great fighter, but I know I can stop him.”

“Time after time,” wrote ringside reporter David Avila of the first Deontay Wilder-Tyson Fury fight, “Wilder’s windmill rights hit air.” But here the Dempsey-Tunney comparisons end. Wilder did find Fury, dropping him “hard and seemingly for good” in the twelfth, Fury undertook his miracle recovery and the unsatisfactory draw was rendered.

What about this Saturday’s rematch? And what about the Tunney-Dempsey rematch? And what about other heavyweight rematches where the puncher and the boxer met for a second time, and what do they tell us about the upcoming meeting between the best and second-best heavyweight on the planet?

The first months of boxer Gene Tunney’s heavyweight championship reign were troubled. He incurred the wrath of New York’s press and public who preferred their champions humble and brutal. Tunney was neither and was actually booed in Madison Square Garden when presented to the crowd two weeks after his triumph. Dempsey was subjected to a two-minute standing ovation that same night, a new experience for him.

Dempsey, the puncher, wrestled with uncertainty about his fistic future before matching the mercurial Jack Sharkey, who was immediately installed as an 8-5 favorite. Here parallels begin to emerge between Dempsey and Wilder who both elected to meet serious opposition behind their nightmare encounter with pure boxers, although Wilder certainly wasn’t an underdog for his November 2019 encounter with Luis Ortiz. Ortiz, like Sharkey, was technically superb and more skilled than his respective punching opponent. Just as Ortiz was able to outbox Wilder throughout their contest, Sharkey set all kinds of problems for Dempsey who struggled to impose himself despite Sharkey’s determination to fight him in the pocket.

And like Ortiz, Sharkey fell victim to a brutal knockout though Dempsey’s victory was awash with controversy and the accusation of a finishing low blow that even modern analysis of fight footage cannot settle. Each man was rescued by his power in a significant fight staged before their respective rematches. But how did Dempsey fare with Tunney second time around?

What was both different and exciting about the second fight was Tunney’s overwhelming confidence in meeting Dempsey’s fire with fire. He didn’t seek a brawl, but he did seek to smother Dempsey’s work on the inside while sharing space with him. Tunney had experienced Dempsey and found him wanting; he dominated their first fight so completely that he feels, now, that he can take certain liberties with his man.

Fury talks like this may be his own thinking. He feels, and is right in my view, that his dominance in the first fight was legitimate, for all that he found himself on the ground looking up. He now talks openly about knocking Wilder out. There is a certain kind of consistency in his thinking; he ruled before and so can rule more directly now. He’s also hyping a fight though, and we all know how that works.

Fury should note that Tunney went straight back to the box-and-move strategy that brought him success in the first fight; he should also note that Tunney was able to hurt Dempsey by bringing him on to accurate punches he himself was sitting down on, especially in the fourth. Finally, it’s worth noting that after ten hot rounds it was Dempsey, not Tunney, who was struggling to reach the final bell despite the latter’s trip to the canvas in the seventh. Just like Fury, Tunney climbed from the canvas and by the end of the round was out-boxing the puncher.

In summary, Tunney became a little over-confident, much to the disgust of his cornerman Jimmy Bronson who repeatedly warned him that he was becoming neglectful of the Dempsey left. For Dempsey, there appears to be no secured advantage from having previously boxed ten rounds with Tunney. He drew a comparable blank to his first effort, despite the knockdown.

Billy Conn was unable to recreate Gene Tunney’s success against the even more fearsome Joe Louis in the 1946 rematch of their legendary 1941 encounter. In that first fight, Conn, contrary to the popular retelling, hadn’t so much hit and run as stayed in the champion’s wheelhouse and tried to stay on him, a declared strategy but one Conn surprised everyone by following through on. In the second fight, Conn froze: “this is going to be the worst fight ever” he told his father-in-law minutes before the ringwalk. Here the balance of power shifted in favor of the puncher mainly due to the ravages of time and the excessive toll they take on the boxer’s legs as opposed to the puncher’s power; Conn substituted his fighting retreat of five years before with a straight-up retreat and was dusted off in eight.

Louis excelled in rematches. Lee Ramage made it to the eighth in their first contest but seemed near death such was the destruction of the knockout he suffered in just two rounds of their rematch. Max Schmeling, famously, out-boxed and out-thought the great Brown Bomber in their first fight in 1936 but was summarily executed in a single round of their rematch. Bob Pastor made Louis “look silly” according to some, and even managed to win a couple of rounds of their 1937 contest; Louis became the first man to stop him in their 1939 rematch. Godoy, Simon, Buddy Baer, all suffered terribly in rematches for one reason: Louis had learned how they moved.

This is the real disaster for any box mover and although he excelled in rematches against all styles, Louis is the ultimate example of this. He may have struggled to find his man on occasion, but once he did, he had found him forever.

Most famously of all, this fate befell Joe Walcott, who extended Louis the full fifteen in the first fight but was brutally dispatched in the rematch. Walcott was a master boxer, a man so smooth he seemed to have been poured rather than born, but he was as susceptible to the heatseeking puncher as the next man. He bedeviled Rocky Marciano in 1952, seemed ahead of him at every turn until, finally, caught by the Rock in the thirteenth he was undone. In the second fight, the puncher found the boxer in just a single round, Walcott decoded by Marciano just as he had been by Louis.

What about Wilder? Does he have that kind of fighting IQ? Can he unravel a boxer of Tyson Fury’s quality having put a serious glove on him twice in the first fight?

It’s a confused picture, but there is data: Wilder has boxed two interesting rematches. The first was against Bermane Stiverne in 2017, having previously handily out-boxed him in 2015. As a promotional prospect it hardly set the grass alight, but in fairness, Stiverne had remained ranked and fought in one of Wilder’s more reasonable title defenses. The fight itself was butchery, and if it were to be analyzed as a part of a pattern it wall fall firmly onto the Louis side of the equation: Wilder learned about Stiverne in the first fight and crushed him in the second fight.

Wilder’s more recent rematch with Ortiz contradicts that notion. It ended, once again, in a savage knockout for Wilder, and that, once again, hints at his having unlocked his man, but in fact Ortiz was once more completely out-boxing Wilder at the time of the stoppage. Wilder, I thought, was even beginning to become a little uncertain.

By the time of the second Stiverne fight Stiverne was on the slide having last won a meaningful fight nearly four years previously, and but one more fight and loss from retirement. Wilder had also improved, and some of his gliding offense belied his reputation at times. The combination is what makes Wilder’s destruction of Stiverne look so Louis-like, I think.

In the second fight with Ortiz, we saw a truer Wilder. Tyson Fury has named him “a seven-year-old with an AK-47.” This sounds a little like Furybabble, but it’s actually rather succinct. Wilder is indeed over-armed relative to his technique and he throws punches that are wildly under-schooled. But that is a part of what makes him so dangerous.

Re-watching him in the second Ortiz fight I was struck by the notion of a wind-up toy rather than a child, a persistent and vitally dangerous one. Wilder didn’t so much decode his opposition as deploy himself with consistent venom and opportunism. It’s a fundamental and sinister combination that clearly makes him difficult to face but I don’t think he’s learning in the way Louis or Marciano learned. I think he’s “just” improving, and a heinous puncher.

What that means for the Wilder-Fury rematch is that the specific nature of the contest will be decided by Fury. It will be he who decides whether to try to out-box the puncher while moving as we saw in Dempsey-Tunney, smother and out-fight the puncher as we saw in Louis-Conn I, or even duel the puncher, something like what we saw Archie Moore try with Marciano. Fury decides. Wilder will just be Wilder.

It all comes down then to Fury’s choice and to each man’s relative preparedness for it. Has Wilder guessed right? And has Fury? A poor selection on strategy would be disastrous.

Lastly, have I got this wrong? If Wilder decoded Stiverne for the devastating second knockout, if he decoded Ortiz thereby stopping him sooner, if he’s channeling Joe Louis in seeing more the second time around, I think there is only one possible winner, whatever version of Tyson Fury shows.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers