Featured Articles

The Friends of Tony Veranis: Part One

The Friends of Tony Veranis: Part One

I suspect that every writer at one time or another wished that some playwright or film maker took a liking to one of his or her articles and ran with it. Unlikely for sure, but hope springs eternal. The following piece is one that carries that hope—that one in a million chance. And even if it makes the cut, it’s kind of moot at my age.

Now this is not about Frankie Carbo who was an underworld force in boxing in the late 1930s and who became the czar of the fight racket ten years later when he controlled the International Boxing Club behind the scenes. Nor is it about Frank Palermo. This is about a slice of dark boxing-related history in and around Boston between 1966 and 1976. Let’s get at it.

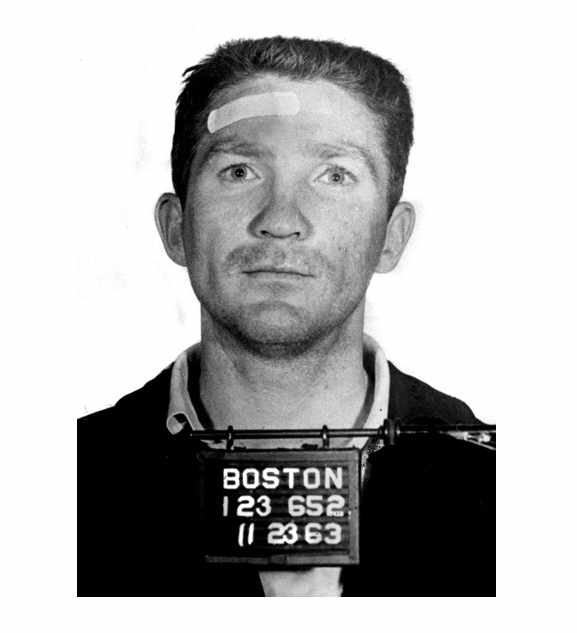

If edgy and nourish crime is your thing, the short and violent lives of Boston boxer Anthony “Tony” Veranis and his friends just might fill the bill. Veranis was a tough Dorchester (Dorchester is known as “The Dot”), Massachusetts kid who was born in 1938 to first generation Italian immigrants from Sardinia. Tony was in and out of trouble for most of his short life as he alternated between professional boxing and low-level crime. He had “Tony” tattooed on the fingers of one hand and “Luck” tattooed on the other, but he didn’t have much of the latter—nor did most of his star-crossed friends.

Labeled a “persistent delinquent,” Tony was incarcerated in 1950 at the infamous Lyman Correctional School for Boys in Westborough, a grim hellhole 30 miles west of Boston. It was the first reform school in the United States and it was where he was anonymously involved in the Unraveling Juvenile Delinquency (UJD) study conducted by Harvard University professors in an effort to discover the causes of juvenile delinquency and assess the overall effectiveness of correctional treatment in controlling criminal careers. If the study led to any positive results, Tony clearly was not included in the academic largess.

While at Lyman, Tony joined the school’s boxing team, and after being spotted by the savvy and acclaimed Boston fight trainer Clem Crowley, he began fighting as an amateur. Tony’s amateur career culminated when he won the Massachusetts State Amateur Welterweight Title in 1956. That same year, at age 18, Veranis turned professional in Portland, Maine under the alias “Mickey White” and won his first pro bout with a fifth round TKO over one Al Pepin. Tony then launched an astounding run of victories, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Tony often sparred with Joe “The Baron” Barboza, Eddie “Bulldog” Connors, Jimmy Connors (Eddie’s brother), Rocco “Rocky” DiSeglio, George Holden, and Americo “Rico” Sacramone. Southie’s Tommy Sullivan also found his way into this mix. The thing about these guys was that in addition to being well-known Boston area boxers, each was brutally murdered between 1966 and 1976.

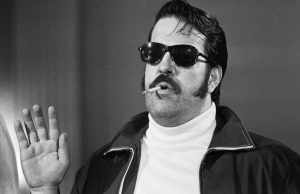

Joe Barboza (1932-1976)

“[Joe was] one of the worst men on the face of the earth.”– Joe’s lawyer, F. Lee Bailey

“The Baron” was his boxing moniker and he learned the rudiments of boxing well at Lyman Reform School. He usually doled out far more beatings than he absorbed. However, a fellow psychopath, Bobby “Dorchester” Quinn, sparred with him and repeatedly beat him until his hands hurt. An accomplished boxer, Quinn was an early opponent of Rocky Marciano. Joe ran up a modest record of 8-5 before taking on a far more lucrative and violent line of work.

It was once rumored that a sparring mate, journeyman Cardell Farmos (12-5-1), had done a number on Joe. Reportedly, the plug-ugly Baron responded by grabbing a gun out of his locker and chasing the pug out of the gym and down the street. When he saw The Baron coming, Farmos jumped over the ropes, ran down the stairs three at a time on to Friend Street, and headed for North Station with the grotesque caveman giving chase.

Barboza also reportedly sparred with Patriarca crime family associate Americo “Rico” Sacramone (who would be murdered), heavy-handed middleweight Edward Connors (machine gunned almost in half in a Boston phone booth), the aforementioned Tony Veranis, who would later be murdered by infamous James Bulger hit man John “The Basin Street Butcher” Martorano (20 confirmed hits), and world class middleweight Joe DeNucci, the future State Auditor for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, who lived clean and stayed clean.

Joe would later assume other nicknames like “The Animal” and “The Wild Thing,” as he became one of the most feared and vicious hit men of his era. He dreamed of becoming the first Portuguese-American inducted into La Cosa Nostra, but the heads of the families were not about to let that happen. Fact is, LCR members called him derogatory names — but always, of course, behind his back.

Employed by the Patriarca crime family of Providence, Rhode Island, Barboza, while operating out of East Boston, allegedly murdered between seven and 26 victims, depending on different sources, but given his methodologies and the amount of fear he generated, it’s clearly safe to err on the higher side.

Notwithstanding his Neanderthal appearance, he was instinctively cunning and did not lack for innate intellect–he reportedly had a high IQ. It was Joe’s unpredictable and deadly disposition rather than his appearance that just about everyone in the Boston area feared the most. Reportedly, even some Boston police would walk away rather than intercede in one of Joe’s street scuffles.

Eventually, Barboza flipped and would become the “Joe Valachi” (aka snitch) of the New England Mafia. The circumstances leading up to that eventuality are grist for a lengthy and intriguing tale featuring, among other sordid elements, corruption, deception, triple-crosses, murder, false imprisonment, and the worse scandal in FBI history. Suffice to say that his testimony helped change the criminal landscape in Boston.

For his reward, there was nothing a grateful FBI would not do, so Joe became the first man in the Witness Protection Program and was sent to Santa Rosa, California, but he soon reverted to form and killed one Clay Wilson for which he served only five years. Upon his release and using the name Joe Donali, he was resettled to San Francisco, but the LCN rarely forgets or gives up, and Joe was soon murdered by four shotgun blasts in 1976. The hit was reputedly carried out by the bespectacled and professorial-looking Mafia captain, Joseph “J.R.” Russo.

Joe had completed his regression from “The Baron” to “The Animal” to “The Rat.”

Joe Barboza was a complex individual whose violent life story begged for a book to be written-and it was by crime author Hank Messick. Titled “Barboza,” it is difficult, if not impossible to find, but is as compelling a true crime story as you could imagine — and if you are a boxing fan, all the better.

Tommy Sullivan (1922-1957)

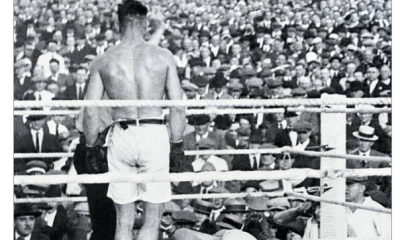

Irish Tommy, as he was known in South Boston, may have been the best boxer of the bunch as he finished with a 20-2 (14 KOs) mark. Tommy went undefeated in his first 17 pro outings until he lost to Al Priest (25-1) in 1946 and then again in 1947 when Priest was 33-2. Among Sullivan’s victims were Eddie Boden (18-0-1), Coley Welch (106-22-6) and “Mad Anthony” Jones who Tommy stopped twice (Jones finished 43-13-4). Fighting before monster crowds of up to 13,000 customers, Sullivan engaged in a number of “”savage brawls” that are still talked about by Boston area aficionados. They include his brutal beatings of John Henry Eskew and George Kochan. Tommy had a knack of coming back after he had been dropped and snatching victory from apparent defeat with a “hurricane attack” in the style of later warriors Danny “Little Red” Lopez and Arturo Gatti. Boston fans loved him for the excitement he brought to the ring.

In January 1949, his relatively brief professional boxing career inexplicitly ended and he began working as a longshoreman at Boston Harbor. While at the docks, he struck up friendly relationships with fellow-longshoremen Thomas J. Ballou Jr. (barroom brawler extraordinaire) and the more infamous Barboza. According to author Howie Carr, Ballou had an unusual style of fighting. It seems he always carried a grappling hook and a $100 bill. If Ballou wanted to attack someone, he’d throw the $100 dollar bill on the ground. The unsuspecting and greedy adversary would bend over to grab it, and then Tommy would plunge the grappling hook into the guy’s back.

Tommy resented gang leader George McLaughlin of Charlestown who had attempted to extort money from one of Tommy’s close friends. For the record, the famous Boston Irish Gang War started in 1961 and lasted until 1967. It was fought between the McLaughlin Gang of Charlestown and the Winter Hill Gang of Somerville led by James “Buddy” McLean, but that’s another long and violent story for another day.

Sullivan made the strategic error of getting into a vicious barroom brawl with Edward “Punchy” McLaughlin and proceeded to give McLaughlin, also an ex-boxer, a vicious beating that could not possibly have been duplicated in Hollywood. Beginning in a bar and then moving outside into the street, the two went at each other on reasonably even terms until McLaughlin finally could take no more punishment and rolled under a parked car to escape. But Sullivan, the enraged Southie native, wanted more and he lifted up one end of the car and propped one of the wheels up on the curb allowing him to get at McLaughlin so that he could continue the beatdown. The throng of onlookers, including Barboza, was amazed at this feat of adrenalized strength that would have made a Hollywood stuntman blink.

Deadly payback was swift in coming. Two weeks later, Tommy was called to the side of a car that was idling in the street near his East Fifth Street home and he was promptly shot five times. Seven years later in 1965, Sullivan’s brawling foe, McLaughlin, was shot nine times at a West Roxbury bus stop. Some suspected Barboza as the triggerman for this execution.

Although he was never put under serious scrutiny for criminal activity, many viewed Tommy within the context of where there is smoke, there likely must be fire.

Rocco DiSiglio (1939-1966)

This former Newton welterweight with a modest record was found shot to death in 1966. Before he turned professional, he trained and/or spared with Veranis, Barboza, Eddie Connors, Sacramone, George Holden, Tom Sullivan, and the legendary Joe DeNucci. He was also a criminal associate of Barboza and Joe would later lead police to the site of Rocky’s corpse in Danvers. It was believed that Rocky was murdered by the mob for sticking up their dice and card games, most of which were overseen by Gennaro Angiulo, the feared gambling czar for the Patriarca crime family.

In retaliation for his brazen, maverick, and foolhardy action, DiSiglio was set up in a Machiavellian-like scheme and eventually shot to death in the driver’s seat of his Thunderbird by the same men with whom he had robbed the card games. He was hit three times at close range with one bullet reportedly tearing off part of his face and another going through his head and out an eye socket. His two killers were later murdered at different times as more loose ends were tied. The entire affair had about it the foul stench of the North End’s Angiulo, and further enraged Rocky’s friend, Joe Barboza, who soon would turn stool pigeon against the LCR.

Still another of Tony Veranis’s friends had died a violent death at a young age.

To be continued…..

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Ted Sares can be reached at tedsares@roadrunner.com

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More