Featured Articles

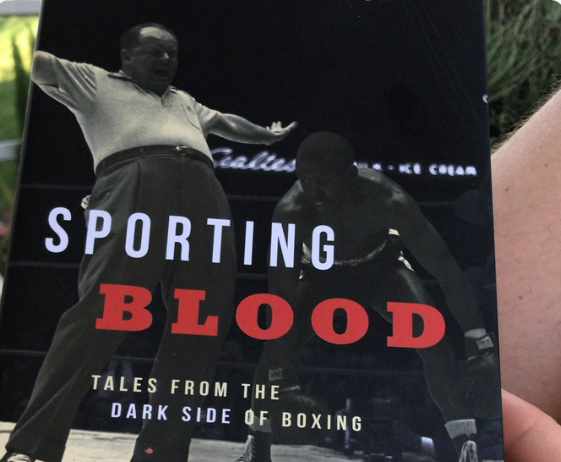

Thomas Hauser’s Foreword to ‘Sporting Blood,’ Carlos Acevedo’s New Book

The Internet has changed sportswriting, particularly when it comes to writing about boxing. Very few newspapers or magazines now have a writer on staff who understands the sport and business of boxing. Meanwhile, the number of websites devoted to the sweet science keeps growing. Some of these websites are quite good. Others are awful. Reprinting a press release with a new lead is not journalism. Simply voicing an opinion without more is not journalism.

As Carlos Acevedo – the author of Sporting Blood – wrote in another forum, “Boxing is immune to critical consensus because of the number of fanboys who pretend to be journalists. No other sport has such an unsophisticated mediascape covering it.”

Acevedo was born in the Bronx in 1972 and now lives in Brooklyn. He was drawn to boxing as a boy, grew up reading The Ring, and recalls being captivated by Larry Holmes, Marvelous Marvin Hagler, and Marvin Johnson. Decades later, when the Internet gave a platform to anyone with a computer and modem, he decided to write about the sweet science.

Acevedo’s journey as a boxing writer began in 2007. Two years later, he founded a website called The Cruelest Sport. Since then, he has written for numerous print publications and websites including Hannibal Boxing (his current primary outlet), MaxBoxing, Undisputed Champion Network, Boxing Digest, Boxing World, Remezcla, and Esquina Boxeo.

“I love the fights and the narrative that comes with them,” Carlos says. “Each fight is a story unto itself; a drama that exposes character and offers the ideal of self-determination.”

I’m not sure when I first became aware of Acevedo’s writing. I do remember laughing out loud years ago while reading his description of promoter Gary Shaw, who Carlos opined “deserves credit for tenacity, like certain insects that become immune over time to Raid and Black Flag.” I first quoted him in my own writing in 2011 in conjunction with less-than-stellar refereeing by Russell Mora and Joe Cortez.

“Incompetence is usually the answer for most of the riddles in boxing,” Acevedo wrote of Mora’s overseeing Abner Mares vs. Joseph Agbeko. “But Mora was a quantum leap removed from mere ineptitude. He was clearly biased in favor of Mares and, worse than that, seemed to enter the ring with a predetermined notion of what he was going to do. Mares had carte blanche to whack Agbeko below the belt as often as he wanted.”

As for Cortez’s refereeing in Floyd Mayweather vs. Victor Ortiz, Acevedo proclaimed, “Cortez, whose incompetence has been steadily growing, is now one of the perpetual black clouds of boxing. Why let Cortez, whose reverse Midas touch has marred more than one big fight recently, in the building at all on Saturday night?”

Acevedo doesn’t have a big platform. He doesn’t have a wealth of contacts in the boxing industry or one-on-one access to big names. In part, that’s because he has never compromised his writing to curry favor or ingratiate himself to the powers that be in an effort to gain access or ensure that he receives press credentials for a fight.

But Carlos has several very important things going for him: (1) He appreciates and understands boxing history; (2) He has an intuitive feel for the sport and business of boxing; and (3) He’s a provocative thinker and a good writer who puts thoughts together clearly and logically.

Look at the “Contents” page of Sporting Blood and you’ll see essays (in order) on Carlos Negron, Jack Johnson, Roberto Duran, Esteban De Jesus, Aaron Pryor, Don Jordan, Joe Frazier, Johnny Saxton, Wilfredo Gomez, Lupe Pintor, Davey Moore, Johnny Tapia, Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, Bert Cooper, Sonny Liston, Jake LaMotta, Ad Wolgast, Tony Ayala Jr, Al Singer, Michael Dokes, Eddie Machen, Mike Quarry, and Muhammad Ali.

That’s an eclectic mix. But each essay goes beyond the name of the fighter attached to it to underscore a fundamental truth about, and capture the essence of, boxing.

Acevedo calls boxing “a dark art.” Phrases like “the hard logic of the ring” characterize the gritty realism of his writing. Some of the thoughts in Sporting Blood that captured my attention include:

* “Sadism, whether one admits it or not, is an essential part of boxing. So is masochism.”

* “Nothing can take away from the terrible symmetry boxing gives its practitioners: a hardscrabble life, followed by a hardscrabble profession, followed by a hardscrabble retirement.”

* “Disillusion is as much a part of boxing as the jab is.”

* “In boxing, the enemies of promise are numerous: entourages, managers, promoters, injuries, other fighters. But self-destruction ranks up there with the best of the worst.”

* “There is very little afterlife for a fighter who has failed to succeed.”

Acevedo has an economical writing style that leads readers to the intended destination without unnecessary verbiage or digressions. Consider his description of Aaron Pryor’s origins, a fighter who Carlos describes as “one of the most exciting fighters during an era when action was a prerequisite for fame.”

After noting that Pryor “matched his unbridled style in the ring with an apocalyptic personal life that kept him in boldface for over a decade,” Acevedo explains, “Aaron Pryor was an at-risk youth before the term came into vogue. Dysfunction was in his DNA. He was born out of wedlock in 1955 to an alcoholic mother whose moodiness could lead to impromptu gunplay. Sarah Pryor, who gave birth to seven children from five different fathers, occasionally whipped out the nickel-plated hardware when some of her brood became unruly. Years later, she wound up shooting her husband five times in the kind of supercharged domestic dispute in which the Pryor clan excelled.”

“Pryor,” Acevedo continues, “had a family tree whose branches were gnarled by tragedy. Its roots were blood-soaked. One of his brothers, Lorenzo, was a career criminal who eventually wound up doing hard time for an armed robbery conviction in Ohio. Another brother, David, became a transsexual hooker. His half-brother was shot and paralyzed by his father. His sister, Catherine, stabbed her lover to death. As if to solidify the epigenetics involved in the Pryor family – and to concretize the symbolism of the phrase ‘vicious cycle’ – Sarah Pryor had seen her own mother shot and murdered by a boyfriend when Sarah was a child.”

Want more?

“As an eight-year-old already at sea in chaotic surroundings,” Acevedo notes, “Pryor was molested by a minister.”

There . . . In a little more than two hundred words, Acevedo has painted a portrait. Do you still wonder why Aaron Pryor had trouble conforming to the norms that society expected of him?

In a chilling profile of Tony Ayala Jr, Acevedo writes, “In the ring, he was hemmed in by the ropes. For more than half his life, he was trapped behind bars. The rest of the time? He was locked inside himself.”

Ayala spent two decades in prison in conjunction with multiple convictions for brutal sexual assaults against women. Acevedo sets up the parallel between Ayala’s misogynist conduct and his ring savagery with a quote from the fighter himself about boxing.

“It’s the closest thing to being like God – to control somebody else,” Ayala declared. “I hit a guy and it’s like, I can do anything I want to you. I own you. Your life is mine, and I will do with it what I please. It’s a really sadistic mentality, but that’s what goes on in my mind. It’s really evil. There’s no other way to put it. I step into that dark, most evil part of me and I physically destroy somebody else, and I will do with them what I want.”

Acevedo also has a gift for dramatically recreating the action in classic ring battles. After recounting the carnage that Ad Wolgast and Battling Nelson visited upon each other on February 22, 1910, he observes, “What Wolgast and Nelson produced was not, in retrospect a sporting event, but a gruesome reminder of how often the line between a blood sport and bloodlust was crossed during an era when mercy was an underdeveloped concept in boxing.”

A vivid description of the December 3, 1982, title bout between Wilfredo Gomez and Lupe Pintor is followed by the observation, “At the core of these apocalyptic fights, where two men take turns punishing each other from round to round, lies the question of motivation. Not in the sporting sense; that is, not in the careerist sense or anything so mundane as competition, but in an existential sense. And while boxing lends itself far too often to an intellectual clam chowder (common ingredients: social Darwinism, atavism, gladiatorial analogies, talk of warriors), the fact remains that what Gomez and Pintor did to each other, under the socially-sanctioned auspices of entertainment, bordered on madness.”

This is powerful writing. Enjoy it.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Reproduced by permission of Thomas Hauser and Hamilcar Publications, the book publishing arm of Hannibal Boxing Media, LLC. Learn more about Sporting Blood and how to purchase it here: https://hamilcarpubs.com/

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – A Dangerous Journey: Another Year Inside Boxing – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. He will be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame with the Class of 2020.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Book Review2 days ago

Book Review2 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds