Featured Articles

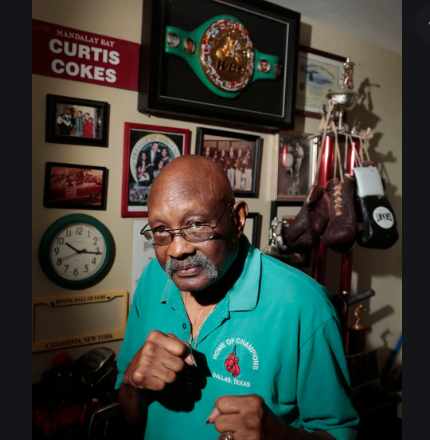

Rest in Peace, Curtis Cokes

Curtis Cokes was born in 1937 into a world of segregation, competing with his seven siblings for the attention of his parents, dreaming of baseball. There is even a story, reported in the Dallas Observer that Curtis nearly made it, that he missed out on a career as a professional baseball player by a narrow margin, returned, from Florida to Texas, and somehow found himself a fighter.

Curtis had no amateur career, although he appears to have been put through his paces in a local YMCA as a teenager. For a black man in Texas in the 1940s making amateur contests was, according to Curtis himself, challenging, so he cut out the middle-man and turned professional, first lacing up for pay aged twenty.

“I just picked it up watching fights on TV,” he told the Cyber Boxing Zone in 2013. “I picked up and copied everything I saw. I would even tie my boxing shoes the way I saw Ezzard Charles do it.”

Just like he saw Ezzard Charles do it. He would be welterweight world champion within a decade.

Watching Curtis box, you can see the Charles influence. He had the same deceptive languid, looseness to his technique, a sense that he was rested when he was anything but, a pleasing fluidity to his work that makes a fighter look natural. My favourite of his readily available filmed performances was his fifth round knockout of Willie Ludick in what was his fourth title defence; the attempted counter-uppercut he throws at forty seconds of the first round is a mirror of the punches Ezzard Charles threw at a befuddled Pat Valentino all those years earlier and just like Charles did to Valentino, Cokes steadily broke Ludick into pieces, technically outclassing, then thrashing him. The orthodox right hand was the classic version of the killing punch.

This was a punch he perfected under the tutelage of Robert Smith, alias Cornbread, a fighter who learned his trade in smokehouses and carnivals before a black champion could even be named a common theme, a fighter who learned the importance of not being hit and not being hurt by the punches with which he was hit, something he imparted to young Curtis while he was styling that right hand.

That right hand and his unerring, shuttering left were what would bring him the welterweight championship but what most fascinates about Curtis’s career is that the man against whom he turned professional, Manuel Gonzalez, was also the man with whom he would contest that title, eight years and five fights spanning their rivalry. Curtis won four of them and on the final, fateful night when Curtis would etch his name on the same historical page as Ray Robinson and Ray Leonard, he won unequivocally, splattering his nemesis with a heavy right hand in the twelfth for a four and then a standing eight count. Curtis followed up but he had to wait for the decision to lift the gold. This was typical of his approach. He was a professional.

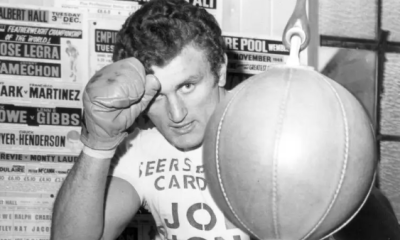

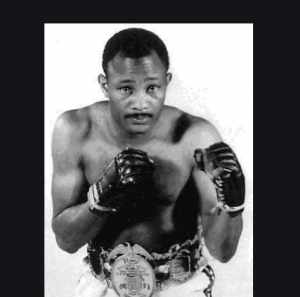

Cokes circa 1965

There was some static surrounding the contest which had been one-sided and less than electric and which was the result of a tournament that had excluded some of the era’s top contenders. For Curtis, though, the main objection was the absence of Cornbread in his corner.

“I don’t know what I would have done without him,” he said of his mentor, postfight, “he always said I’d win the title. Too bad he couldn’t see it. He’s dead. He was with me anyway.”

Curtis though, was very much alive, and he would go on to defend his title on five separate occasions, all the way through until 1969 when the great Jose Napoles found him.

Before he had even come to the title, however, Curtis had rendered himself immortal in a series of fights with the great Cuban, Luis Rodriguez. Rodriguez, who is famed now as much as anything for his series of fights with the great Emile Griffith, was arguably unbeaten in those contests but he couldn’t live with Curtis. The two met in three titanic contests in the sixties and Curtis emerged with the best of it, finally stopping the Cuban in the fifteenth round of their third contest.

“I beat him pretty bad,” Curtis said of their first fight, “I had him down and earned me a PHD.”

Curtis lost the second fight but had his opponent’s number by the time of their third fight, slowing him down with a body attack and taking away his legs, much to the chagrin of Angelo Dundee who was training Rodriguez. This superstar pairing meant nothing to Curtis who “turned tiger” in the fourteenth round and “resumed the assault in the fifteenth” (Associated Press) prompting the superstar trainer’s signal of surrender on behalf of his superstar charge.

Curtis was never a superstar. He was underrated then, starting as an underdog, and he’s underrated now, often appearing below Rodriguez on modern-day welterweight all-time great lists, if he appears on them at all.

He flirted with stardom himself upon retirement though, appearing in the superb fistic movie “Fat City”, playing his non-fistic part with the same understated excellence with which he fought his fistic career before returning to Dallas and opening a boxing gym with an eye on keeping kids off the streets and out of trouble.

“I started out wanting to be world champion and I accomplished that,” he told Mike Silver in 2014. “I’m in the Hall of Fame. I retired from boxing because it was time for me to go. Nobody took advantage of me. Before I became a pro I attended college for two years. I had a good education. I knew how to take care of myself. I knew how to count my money too. I didn’t need a manager to count my money to me. I counted out my money to him.”

The rare glory in that should not be underestimated.

His death of natural causes this Friday at the age of eight-two has been predictably under-reported. I suspect it may not have displeased him.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More