Featured Articles

Iran Barkley and Junior Jones: After the Final Bell, the Real Fight Began

Iran Barkley and Junior Jones: After the Final Bell, the Real Fight Began

A TSS CLASSIC — The stifling heat of Gleason’s Gym in Brooklyn makes for an unforgiving environment, and it seems to be taking its toll on the grunting heavyweights sparring in the main ring.

A muscular black fighter, who has made fifteen professional outings and considerably outweighs his pale amateur opponent, is dominating the affair. With one minute remaining, the pro unleashes a sustained barrage of heavy hooks to his opponent’s

head. The despondent novice is backed into a corner and absorbs the blows with little resistance as his nose ruptures, turning his white face into a crimson mask.

Most ringsiders holler in approval at the striking power. But one observer is not impressed.

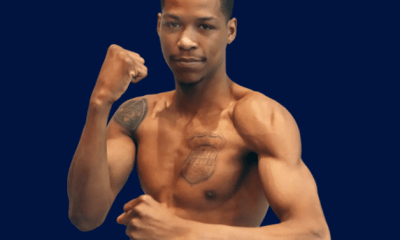

“Hey, hey, that’s not right, shouts Iran Barkley, a physically imposing 220-pound ex- pug that wears the remnants of a 63-fight career on a battle-scarred visage. “Sparring is about learning, not getting beat-up. Nobody gets anything out of a beating.

As the vanquished fighter exits the ring holding a claret-stained towel to his nose, he is approached by Barkley. “Yo, you’re not here to get beat-up, offers the three-time world champion. “Don’t let anyone do that to you. You have to look after yourself.

Barkley’s act of empathy contradicts his reputation as a malevolent slugger who held membership in New York’s violent Black Spades street gang.

After consoling the bloody novice, the 49-year-old Barkley strides with his head-down towards a treadmill to begin an hour-long exercise routine that includes calisthenics, weightlifting and shadowboxing.

Midway through the workout Barkley pauses to wipe the trickles of sweat from his shaven skull. His left eye is barely visible through a thick mass of tissue that overhangs his brow; an everlasting consequence of claiming world titles in three different weight

classes, ranging from middleweight [160 pounds] to light heavyweight [175 pounds].

“I like to work out as much as I can, he says. “I also work a few days a week helping out kids in a neighborhood in the Bronx. It gives me something to do.

*****

A bank worker’s attempts to casually ascend the steps from Manhattan’s Penn Station are stymied when an opposing swarm of rush-hour commuters surge down the stairway. His unassuming demeanor proves no match for the bustling horde and his slim frame quickly becomes lost in a wave of humanity.

There is an added element of chaos to the busy walkway on 34th street as noisy groups of hockey fans make their way towards Madison Square Garden. Big events at the fabled arena create a unique energy in the vicinity; energy this worker has experienced in a deeper sense than most.

A nose curved where it should be straight and flat where it was once curved alludes to Junior Jones’s former profession. He fought at the Garden on six occasions during a 56- bout prizefighting career; an occupation far removed from his current employment

in an administrative role at a New Jersey branch of the UBS financial services firm.

These days his work is conducted during daytime hours, but walking past the Garden rekindles memories of big nights at the fabled arena.

“It was such a rush fighting there in front of my hometown fans, says the Brooklyn-born Jones in a soft tone that belies the brashness of his surroundings. “But sometimes in the Garden I tried so hard to impress everybody that I got carried away.”

Inside the ring, Jones was often guilty of letting his emotions overrule rationale; yearning a spectacular knockout instead of utilizing his polished skills. Such an attitude helped him halt 28 of his opponents inside the distance and merit recognition as one of leading fighters of the mid-1990s. That mind-set also saw him suffer five knockout defeats that mark his 50-6 record.

Yet despite the turbulent nature of his former career, Jones has no ill-feeling towards the outcome of a 13-year pro tenure in which he won major world titles in the bantamweight [118 pounds] and junior featherweight [122 pounds] divisions.

“I don’t miss boxing and I’ve no real regrets, explains Jones matter-of-factly as he takes his seat in a Manhattan restaurant. “I know I did the best I could do and fought my heart out every time. I loved fighting and at times I overextended myself. But people come

to see a fight, not to see me run around the ring with my hands up. People pay good money.”

Smartly attired and perpetually understated, Jones seems to take greatest pleasure in talking about his two children and current job, making it difficult to believe he engaged in some of the last decade’s most exhilarating fights. And while his last professional contest was in 2002, he maintains an athletic build and looks younger than his 39 years.

“I work out at a gym I own in Brooklyn and I know that if I train hard, I still have enough left to beat a lot of the guys out there, he imparts with a wry smile.

Iran Barkley and Junior Jones share many similarities. Both fighters managed to distance themselves from street life in their respective deprived New York neighborhoods to achieve world titles and significant monetary rewards. The formative years were challenging for both men and each points to a sister as the catalyst for a boxing career.

“I was a skinny teenager and there was a big bully called the Bear who would steal kids’ money and sneakers,” recalls Barkley, who grew up in the menacing environs of the South Bronx Patterson housing projects. “I was really afraid of him but one day he ran

into my sister and he never touched us again.”

Barkley’s sister Yvonne was one of the pioneering professional female boxers and routinely defended her younger sibling. But a few years later Iran grew into a wild street fighter and became a valuable asset to the local gang. As his involvement with the Spades intensified, Yvonne appealed with Iran to turn his attention to boxing. He eventually heeded her pleas and after tasting amateur success developed a fanatical obsession with the sport.

“I trained non-stop,” Barkley says after completing 50 sit-ups on the floor of Gleason’s. “I worked so hard, obsessed to get my world title. When I look at some of my cousins who were dealing dope, now some of them are in prison for 30, 50 years or more, I feel

blessed I chose boxing and didn’t take that route.”

***

Jones’ sister was also an inspiration, albeit in a rather less benevolent manner. “My sister Renee used to beat the hell out of me, hit me with pots and pans, put me out on the fire escape with no clothes,” he reveals with a bashful smile. “People used to laugh that I couldn’t beat her up.”

Jones’s humiliation came to an end when he joined the Police Athletic League gym in Bushwick and eventually gained the respect his neighbors.

“It was rough where I grew up, but the older guys, hustlers and drug dealers got to know me and knew I was doing well at boxing, so I was protected,” he explains. “But I was never a follower. I was in the gym, I was travelling to competitions somewhere. I didn’t

have idle time.”

Jones had an exceptional ability to generate fierce punching power and earned distinction as a world titlist in 1993, overcoming Jorge Elicer Julio. But two consecutive upset defeats to relatively obscure journeymen severely damaged his standing. Even so, he worked his way back to contention and outscored future Hall of Fame entrant Orlando Canizales before being awarded a title opportunity against one of the era’s great fighters, Marco Antonio Barrera.

While many boxing observers rightly denounced Jones’s chances, the fighter retained the unwavering support of his long-time manager Gary Gittelsohn. In an uncommon attempt to instill confidence in his charge, Gittelsohn vowed to forsake his fee from Jones’s purse regardless of the fight’s outcome.

“I didn’t take the money because I always had confidence in Junior that he would win and go on to become a big star,” said Gittelsohn about his act that refutes the grubby reputation of boxing managers.

Jones ultimately repaid Gittelsohn with a rousing performance that resulted in a fifth- round disqualification victory when members of Barrera’s team entered the ring to rescue their dazed fighter. Jones subsequently proved the triumph was no accident by out-toughing Barrera in a rematch five months later.

That win would be the zenith of his achievements and was followed by inconsistent performances. Gittlesohn urged Jones to retire after a loss to Erik Morales in 1998 and again declined to take a management fee from his fighter’s check; this time without the

expectation of future remunerations. And even though Jones didn’t heed Gittlesohn’s pleas, he remembers with fondness the actions of his manager. “I was lucky to have him, remembers Jones. “He always stuck by me. I put the money I made away and invested it in trusts for the long-term. And now I’m not struggling financially, thank God.”

Back in the searing temperatures of Gleason’s, Barkley has just completed six minutes of shadowboxing and is walking towards a set of weight machines when he encounters the black heavyweight from the earlier sparring session. The young fighter, relaxing on a bench, calls out to Barkley.

“Hey man, I recognize you,” he yells. “I know your face.”

Barkley coldly nods his head at the fighter and keeps walking, perhaps disgruntled that his name is not remembered.

“Fighters these days,” remarks Barkley as he picks up a 20-pound dumbbell. “They’re not as tough today; fighting whoever they like. They have it easy, getting paid more and having easier fights.”

Money is a thorny issue with Barkley. Despite reaping an estimated $5 million during his prizefighting career, he now lives a meager existence in the same housing projects he grew up in. He cites a lack of financial knowledge as the cause of his current

predicament.

Barkley burst onto the global boxing scene in 1988 when he shockingly knocked out the much-vaunted Thomas Hearns for the middleweight title in one of the sport’s great upsets. And like Jones, Barkley vindicated his unexpected triumph by out-pointing

Hearns in a light heavyweight rematch four years later.

In between the battles with Hearns, Barkley suffered competitive defeats to some of the period’s elite fighters, most notably Roberto Duran, Michael Nunn and Nigel Benn. He also captured a super-middleweight world championship by overpowering Darrin Van

Horn.

But in another parallel to Jones’s career, Barkley’s second victory over Hearns proved to be his final significant pugilistic conquest. One year after that rematch, Barkley garnered $1 million for a one-sided loss to the exceptional James Toney. The subsequent six years saw Barkley traverse America and venture to Australia and Europe in search of paychecks on small-time promotions. He lost as many fights as he won and on many occasions weighed 60 pounds greater than the middleweight limit, as the competitive edge that once earned him the moniker “Blade” steadily dulled. In 1999, his final year as an active fighter, Barkley traveled to Finland to lose a 12-round decision in a pitiful spectacle against former WWE wrestler Tony Halme.

“I take some of the blame for my [current financial] situation, but not all of it,” contends Barkley. “Years ago, I just didn’t know what to do with money when I had it. My family never had much when I was growing up. I didn’t know how to save, how to invest it.”

While Jones had the watching eye of Gittlesohn, Barkley lacked such stable guidance and was under the management of various figures throughout his career. “I had to teach them how the boxing game worked,” Barkley claims.

“I learned that my only real friend is God,” he continues, with his eyes fixed on the grimy gym floor. “Everyone else will let you down in the end.”

Some of his money was invested in apartments and a car wash facility, but the ventures proved loss-making and after tax issues and two divorces his wealth evaporated.

“I don’t know where his money went,” says the owner of Gleason’s Gym, Bruce Silverglade. “But he always helped people out. He’d give you the shirt off his back. He has a heart of gold. Even today he’s always willing to talk at hostels and to kids.”

But such admirable efforts fail to pay the rent.

Barkley now lives in an apartment with his sister and nephew in the Patterson Houses. He lost two of his brothers to cancer and his sister is currently hospitalized after recently developing a long-term respiratory illness.

Earlier this summer Ring 8, a New York-based group that provides assistance to retired boxers, held a benefit dinner for Barkley, but he says the funds generated at the event have already been spent. He claims a return to prizefighting is the only long-term

answer to his financial problems and has informed the sport’s major promoters of his intentions. Thus far his approaches have been firmly dismissed.

“I can’t get a promoter yet,” he reveals. “But someone somewhere will promote me. I’ve no fear of boxing. I got through twenty years without getting hurt.”

At present there is no official financial aid package for retired prizefighters, but Barkley says he has been in touch with a number of politicians in New York with the goal of lobbying for a pension plan. “Look at everything I put into boxing,” he laments. “Ex-

fighters like me should be getting something. I want to have enough to provide for myself and my four daughters.”

Yet Barkley has been presented with multiple opportunities to find a new direction in his life. Post-retirement, he worked brief stints as a car salesman and shop assistant before getting bored with the roles. He also had the opportunity to train fighters, but admits he

found it difficult to relate to pupils that lacked the same tenacity he was renowned for in his prime.

“I want to work for myself and I’m not going to chase fighters around either,” he rasps. “I’m not calling a guy to make sure he comes to the gym. If they don’t have the same determination and commitment that I had then I’m not interested. I want to be able

to find and promote talent, but I have to get a lot of money together before I can do that.”

***

Changing careers can be a difficult endeavor, especially when a man has tasted the adoration that accompanies world championships and million dollar paydays. And as Junior Jones can attest, moving into an alien environment can be intimidating, even for a prizefighter.

“When I retired I’d never worked a day in my life, I was terrified of working,” Jones admits. Sitting in the noisy restaurant, he keenly pulls himself forward on his chair, eager to engage as his widening eyes oppose a subdued voice.

“I’ve got a great job and I like everybody there,” he says. “I really enjoy it. I don’t miss training. I don’t miss anything about fighting at all. I’ve done it at the highest level and I accomplished more than I ever expected to accomplish. What’s better than that?”

Superficially, two years of managing deposit slips and checks at a bank may not seem like the most stimulating time in Jones’ life, but the occupation seems to have provided him with a security that transcends wealth.

“You have to be comfortable who you are,” he says. “I like who I am now.”

Having sprayed a steak sandwich with mustard, Jones prepares to take a bite. But he abruptly becomes uncharacteristically agitated. The subject of aged fighters flouting retirement has just been raised. Jones puts down the sandwich, shakes his head and

exhales in vexation.

“It’s crazy for guys to be fighting past 40,” he says while stabbing his finger at the table. “The fighter knows when it’s over and it’s the fighters that make the sport bad too, not just the promoters. Some fighters like people telling him they’re going to win and get

back to the top.”

Jones retired days before his 32nd birthday after taking a sustained beating from unheralded journeyman Ivan Alvarez. Even though a fighter may leave his profession with faculties intact, the symptoms of punch-induced brain damage can take years to

appear. A variety of observers have expressed concern at the apparent decline in the clarity of Jones’ speech. His voice was never particularly voluble, but in recent years it does take greater effort to discern his sentences.

In contrast to Barkley’s dismissive approach, the physical costs of a boxing career do perturb Jones, whose pensive personality has led him to explore the worst possible scenario. His eyes look downward as he describes the brutal consequences of a

prizefighting vocation.

“You’re getting hit with an eight or ten ounce glove with a pair of [hand] wraps on and gauze and tape,” he says with a sense of reluctance. “Your brain sits on top of your head in fluid and every time you get hit, your brain hits against the skull. It crashes the wrong way.

“I want to stay the way I am now, he declares. “I want to be like this as my kids go to college and remember everything they do.”

While Jones has successfully redefined his life since retirement, no matter how far he distances himself from boxing he knows nothing can reverse the effects of absorbing countless head blows. “I’ve been fighting since I was ten; all that adds up,” he acknowledges. “I’m fine now but will I be the same when I’m 50 years old? The scary truth is it’s not a guarantee.”

***

After leaving the highly-charged atmosphere of Gleason’s and sucking back a bottle of iced tea, Barkley seems rejuvenated as he takes a deep breath of the cool air and heads toward Clark Street subway station.

“It’s good to do a workout,” he says. “I always feel good afterwards.”

Upon entering a crowded subway carriage, Barkley moves to sit down in the last remaining seat but quickly jumps back up when he sees a woman with a crying young boy enter the train.

“These subways can be intimidating if you’re not used to them,” he remarks in reference to the wailing child.

Barkley then spends the short journey making comical faces at the boy, pulling goofy smiles in a successful effort to put the youngster at ease and distract him from the daunting surroundings. The distinctive facial features that were so intimidating in

Gleason’s now act as a soothing source of comfort.

Leaving the train, our conversation turns to Barkley’s past trips to Europe and the sudden death of Tony Halme earlier this year.

“Wow, no way!” Barkley exclaims, evidently surprised at the news. “Wow, I didn’t know he died.” Barkley pauses and looks into the distance. “Halme seemed so big and strong,” he finally remarks. “You never know what’s around the corner. I guess it puts

my problems into perspective.”

Editor’s note: This story by award-winning writer Ronan Keenan first ran on Aug. 17, 2010. The photo is of Gleason’s Gym.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Shafting of Blair “The Flair” Cobbs, a Familiar Thread in the Cruelest Sport

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden