Featured Articles

Every Joe Gans Lightweight Title Fight – Part 4: Rufe Turner

Gans left the ring without a scratch – The Brooklyn Eagle, 25th July, 1902.

Rufe Turner was a puncher.

Between the dawn of the twentieth century and his July 1902 confrontation with Joe Gans, he went 16-3-2; all but one of the victories came by stoppage and all his losses were on points. Turner dried up during the last decade of his career but in his pomp, he was all knockouts and jaw. He had faced down fellow punchers, men like Mike “Dummy” Rowan or “Irishman” Tim Hegarty, but he had never faced a composite puncher like Gans.

For Turner though, in 1902, there was no choice. His pursuit of the lightweight championship was the pursuit of a knockout, stop or be stopped, hurt or be hurt. There was no other way.

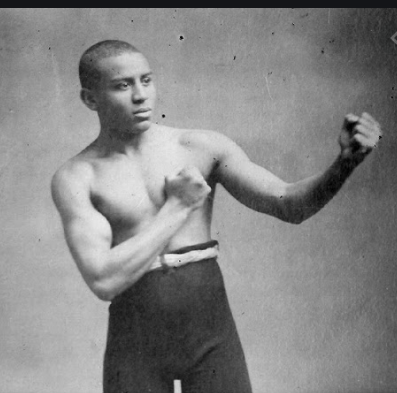

Three weeks before he would mount his assault on the title, Turner was working his magic on an inexperienced fighter named Willie Lewis in Stockton. Lewis, who was noted as “making a speciality of black men” in The Stockton Daily Record, worked well, attacking Turner two-handed but walked into what one ringsider called Turner’s “sledgehammer punch”; the result was a ten-count which finished long before Lewis regained consciousness. Turner spoke the name Joe Gans; Joe Gans (pictured) bid him west.

“[Turner] has agreed to box Joe Gans fifteen rounds before the Acme Club, Oakland, on the night of the 24th,” The San Francisco Call reported two days later. “The fight between the two colored men should be a good one.”

Turner, like Gans, was African-American.

There is a perception that fights between two fighters of African descent was of no interest to the American public in 1902, but this is not true. First, there was an emerging class of “sporting men” who were African-American, and they had money to spend, sometimes spent it on gambling and when they gambled it was often on fights. Second, there was a whole generation of white gamblers who bet upon what they saw, and who would bet on anything, including a prize-fight staged between two fighters of whatever race the promoter might wish to source. Finally, there was stardust – if a black fighter was special, the public would pay to see him.

Still, that Gans reigned as champion so soon after his quit job against Frank Erne and his widely derided fake with Terry McGovern spoke of his irresistible quality. The storm that was Jack Johnson was, even then, gathering for a crack at the heavyweight championship but men like Gans, the wonderful George Dixon and the Barbados Demon, Joe Walcott, beat him to the punch in lifting championships; but a certain conduct was expected of these men, there were limits. While Johnson would turn those expectations on their head in what was probably the most important contribution sport ever made to redressing black-white relations in that troubled time in America’s history, Johnson drew the colour line when he came to power, refusing title shots for most of the African- American fighters who had dogged his steps to a title shot.

Gans, in his third title defence, met the most dangerous lightweight puncher in the country who shared his heritage and that is worth noting. The San Francisco Chronicle, which, it will be remembered from Part Three, was most accusatory of Gans over the McFadden fight, could not have been happier noting that there was “no more worthy opponent in California” and that Turner could be favoured “if he can only forget he is going against the champion lightweight.”

Gans set up training quarters minutes south of Oakland in Alameda.

“I have fought hard for the championship,” he told pressmen. “And now that I have it, I will take no chances losing it. This fellow Turner may be a good, clever fellow, but he will find he is up against a seasoned fighter…You can bet your money I will be the winner.”

The Oakland Tribune stood in admiration:

“The hardy, clever fighter is in the most amiable mood,” one writer purred of his visits to the Gans camp. “Cheerfulness has always been a characteristic of Gans, and it is a characteristic which aids wonderfully in the development of a man training for a fight…[his] muscles are hard as steel and his limbs supple, and every joint moves with an ease.”

Turner, at first, was silent, but his people were not; a special train was scheduled to bring his admirers to the fight. “Turner is looked upon as invincible in Stockton,” stated The Tribute. “His wonderful showings in the ring of late has his stock way up.” Meanwhile the pugilist himself prepared overwhelmingly with heavy sparring, his normal course, but those who knew him were struck by a single difference, specifically a care over his work that had not been present before; where once he had done as he pleased, now he sought council, although nobody could convince him to move his fight camp to Oakland.

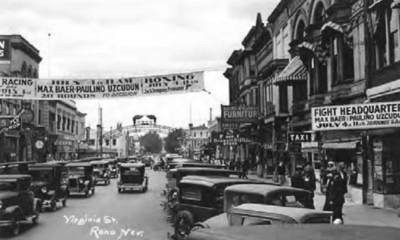

Despite the fuss, Gans-Turner suffered stiff competition in terms of build-up. No less a figure than James J Jeffries boxed his first defence of the world’s heavyweight title against former champion Bob Fitzsimmons the same weekend, and locally, in San Francisco. I submit that Jeffries dwarfed even John Sullivan as a superstar from this era, although he had not summited quite yet. Nevertheless, The Call was not alone in noting “unusual interest” in the Gans-Turner fight. Gans, already, was providing competition for the biggest and brightest, and for all the heavies stole many of the headlines, the draw of the eyes of the sporting world to the area could only benefit the two lightweights. Many who had spent fight week in San Francisco for the Jeffries fight spent the evening before in Oakland for the Gans fight. The Acme Athletic Club would be filled to near capacity.

Turner pulled his training two days before the fight and two pounds underweight, a picture of relaxation. He went off to San Francisco and then Oakland the following day. The same day, Gans worked hard but somehow took on a sliver of weight and was forced to run miles the day before the fight, up to ten by some reports. Battles with the weight were not unusual for Joe and usually entailed taking off only those final, stubborn ounces. Turner seemed principally interested in Joe’s weight and even when he was told that Gans continued to spar with former foe Herman Miller while Turner rested, it was the champion’s poundage that moved him. Turner apparently insisted often and loudly in the final days that Gans should make 135lbs, on pain of a $200 forfeit, something that would return to haunt him. To his credit he was also dismissive of any notion as to the fight being another fake, laughing or shaking his head whenever a newspaperman suggested it.

The interest was such that some local papers were by now outright favouring the lightweights over the heavyweights, The Stockton Evening Mail complaining that Jeffries was so the superior of Fitzsimmons that the fight was a foregone conclusion. The Los Angeles Times meanwhile, broke ranks and became the first paper to pick Turner, favouring him for not only his vaunted punch but also for the ease with which he made weight. It is fascinating to note then that it was Turner, not Gans who took extra weight to the ring, coming in at half a pound over while Gans hit his mark. It was Turner, and not Gans who was subject to the fine and muttered accusations of an unfair advantage.

These were thrown into sharper relief by the condition of Gans who had “trained down fine” in the parlance of the day, ribs visible beneath his flesh, his face angular and taught. It is testimony to his discipline and his commitment to his art that he would still be making the 135lb limit some seven years later.

Discipline and professionalism seem the cornerstones, too, of his victory over Turner. It was clear within minutes that Turner had a single chance and that chance involved Gans carelessness intersecting with a flush overhand right, so Gans set out to eliminate those errors and minimise those risks, and this, he did, throughout the fight – until the very final seconds.

Gans could and perhaps should have taken out his man in the first, however, as Turner was clearly overwhelmed by the occasion. It needs to be remembered that this wasn’t a twenty-two-year-old Olympic hero getting the first of five title shots at one of twenty “world titles” spread across four different divisions and separated by increments as small as three pounds; this was a black slugger boxing in an openly racist era against a pound-for-pounder for the only world title he would ever be matched for – and he probably knew it.

It should be remembered, too, that The Chronicle had made Turner a slender favourite but only if “he can forget” the enormity of the occasion. There were some questions concerning Turner’s championship minerals and these proved to be well-founded. According to The Tribune, Turner “evidently feared the champion” and “went down three times in this round from sheer nervousness.” Making sense of this is not easy, and reports are contrary, some describing scuffling but most agreeing that Turner was taking to the canvas without a punch being thrown, much less landed. Gans intimidated people. Even Elbows McFadden, who shared so many rounds with the champion seemed over-wrought in their most recent and final contest. Turner was visibly afraid.

For his part, it can only be imagined the horror Gans was filled with as the spectre of yet another faked fight loomed but Turner gathered himself, recovered his mind and set out in earnest to win the world’s championship. Gans remained cautious.

“Joe saw that the work cut out for him was easy,” The Chronicle wrote, “and he took his time, fighting a careful, waiting battle with the right ever ready to put an abrupt ending to proceedings when the proper time arrived…no matter what position he got in during the mix he never left either the head or body unprotected.”

Gans, careful, shifting, feinting, but never extended, allowed Turner to develop momentum. Key for Joe Gans: it does not matter unless the offence is absolutely elite. Momentum does not matter, fluidity, cohesion, speed, none of it matters because Joe Gans has an absolute measure of any fighter merely excellent with whom he takes to the ring.

“His blocking was wonderful,” reported The Tribune, “and it may be said that Rufe only succeeded in getting one really good clean blow [in the entire fight].”

This “one blow” remark is disputed, notably by the gambler Finny Jackson, who from a ringside seat saw Turner land two good body punches in round three. Whatever occurred in the third, Turner began to overreach in the fourth and his long and painful execution began. At round’s end, a rapid left-hand counter dropped Turner for the nine count; when he regained his feet, Gans hit him again with a reverse one-two and Turner was dropped once more, saved only by the bell.

This is important to note. Joe’s perennial critics at the San Francisco Chronicle alleged after this fight that Gans let Turner survive into the fifteenth to allow his manager to collect on bets. It is true, such things were not unheard of but here in the fourth Gans blasted Turner to the deck for a nine count and then pasted him again when he made it up, only the bell interrupting the count. If Joe was trying to avoid the early knockout, he was playing with fine margins.

Turner landed a good right hand high on the head in the fifth and enjoyed his best round of the fight in the sixth, landing the one good blow identified by The Tribune, a left-handed body shot so violent it lifted Gans from the canvas. This sounds hyperbolic, but it was reported in both The Tribune and The Chronicle and the champion’s offence was momentarily stymied. His defence, meanwhile, seems almost to have been impregnable these occasional punches aside, while Turner threw and threw and threw and wilted. Gans meanwhile “never wasted a punch” even according to the ever-critical Chronicle, boxing with absolute economy in the face of a fighter attempting to throw himself into relevance.

The San Francisco Examiner saw a total of three clean punches landed by Turner, their favourite a right hand to the heart in the eighth. Nevertheless, this was another round that saw Turner spilled to the canvas, though he was up quickly and straight back to the fight. It was in the tenth that the fight started to feel cruel, Turner dropped twice, first on his face with an uppercut to the stomach, then with headshots that sent him crashing through the ropes. The bell saved him for a second time, a fact once again overlooked by The Chronicle which itself reported the awful beating Gans administered in the thirteenth in another round where perhaps only the bell and a hard head combined to see Turner through.

The San Diego Union and Daily Bee has Turner hitting the deck in the fourteenth but no other source repeats the claim. In the fifteenth, Gans closed the show. In a repeat of the thirteenth, Gans landed headshots almost at will, eventually putting Turner out of his considerably misery. This was an experienced, powerful man but against Gans he appeared little more than a middling sparring partner. “Gans never took a chance at any stage,” noted The Bee. “Even when Turner was groggy and an easy mark…he kept away or jabbed easy ones to Rufe’s face.”

Nevertheless, there was marked admiration for Turner’s staying power which was considerable. “You’re alright old man,” Gans told his fallen opponent as the two shook hands. “There was sincerity,” reported The Chronicle, “for the Stockton boy made a truly brave showing.”

The Stockton boy fought on and in fact went fifteen fights and two years undefeated. In 1905 he even found his way back into Joe Gans’ ring, though for a six-round no-decision rather than a championship fight. Most sources made Gans a handy winner, but the fight contained none of the spite Gans unleashed against him in the fourth round of their title fight.

Turner fought another twenty years, a third and fourth career, fading but never falling entirely to pieces. He fought on several occasions for something called the “Orient Lightweight title” and supposedly made the acquaintanceship of Pancho Villa, even showing him a thing or two in the line of punching according to Bill Miller, who had indeed spent some time in that part of the world.

Jack Kearns, too, sang Rufe’s praises as a puncher and even spun a tall tale in which he boxed Turner, stopped on his feet after nine. Some sources have him boxing into the early 1920s, his fourth decade as a fighter. Turner was never going to make a champion in the early 1900s, but he likely had the punch and the heart to hold a strap in our own time.

Gans emerged from this fight without a mark on his face and he was not for resting upon his laurels. Al Herford, campaigning as always on Joe’s behalf, began work in tempting Jimmy Britt into the championship ring. First though, there was the matter of Gus Gardner who he met just two months after dusting Turner in a fight that had originally been named a title fight only for Gardner to miss the weight by three pounds. If there were any truth to the notion that Gans had held back against Turner, he certainly did not do so against Gardner, who he blasted out in five of a scheduled twenty. Gardner does not appear to have landed a meaningful punch. Once more, reporters made the claim that a Gans opponent appeared to be “nervous” and in the case of a writer for The Waterbury Evening Democrat, outright scared.

Still, Gardner fared better than Jack Bennett who Gans knocked out in two one-sided rounds five days later. Bennett was a seventy-fight veteran who had, in the preceding eighteen months, been in with the likes of former welterweight champion Rube Ferns, George McFadden, Mike Sullivan, not to mention Joe Gans himself. But something had changed. Bennett now “appeared to be afraid of the champion” according to the Washington Evening Star.

Gans dropped him twice in the first and then put him away with his new pet, a reverse one-two, in the second.

The following month Gans departed once more for Canada, Fort Erie, the site of his great triumph over Frank Erne. His opponent was an old foe, one who had extended him twenty-five rounds in 1898, the veteran Kid McPartland. But the question now seemed a different one to that which was usually asked, not as to who could beat Joe Gans, but as to who could face him without fear.

This series was written with the support of boxing historian and Joe Gans expert Sergei Yurchenko. His work can be found here: http://senya13.blogspot.com/

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates